The Armory Show shares its name with its historically significant predecessor following a brief stint at the same 69th Regiment Armory. While today’s Armory Show is now in its twelfth year and situated on expansive piers along the Hudson River, it no doubt benefits from association with the formative 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art. However, positioned within a global art context that is increasingly homogeneous and accessible, today’s art fair could never shock audiences or transform the landscape as its 20th century predecessor once did. Instead, The Armory Show offers its visitors a temporary microcosm of the global contemporary art market geographically reduced to the confines of its venue.

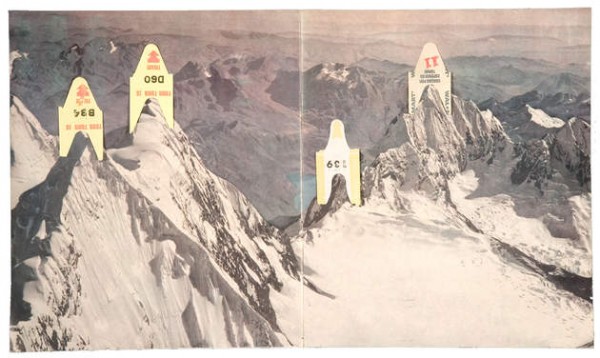

Untitled (Montanas), Gabriel Kuri (2011).

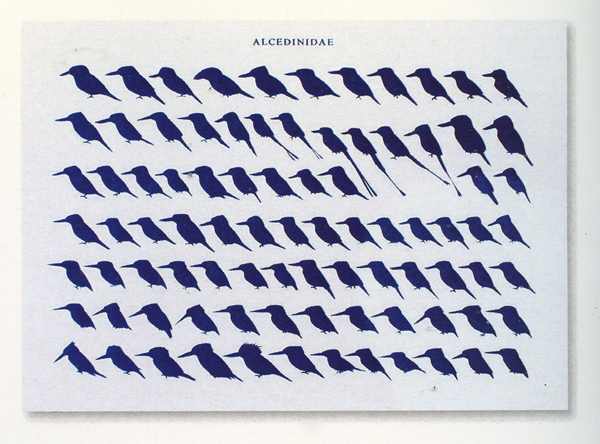

Armory Arts Week has become an annual event held March 3rd through 6th, centered on The Armory Show. Competing venues have multiplied throughout the city of New York, including The Art Show, Pulse, Scope, Independent, Verge (Art Brooklyn), Moving Image, Red Dot and Fountain. Headlining these fairs, The Armory Show 2011 continued its dual focus on both modern and contemporary art with Pier 92 focusing on the 20th century and Pier 94 accommodating nearly two hundred contemporary art exhibitors. The fair’s limited program included Armory Focus: Latin America, comprised of eighteen galleries highlighting Latin America’s contribution to contemporary visual art. The Armory’s annual commission to create a visual identity for the fair went to Mexican-born conceptual artist Gabriel Kuri. Also associated with the fair were Art Projx Cinema and Volta NY, a fair which presents solo artist booths in a smaller format.

DailyServing brings its readers highlights from The Armory Show and Volta NY.

Subway (2010), © Leandro Erlich, Courtesy Sean Kelly Gallery, NY

The Armory Show: Sean Kelly Gallery

Sean Kelly Gallery in New York presented Leandro Erlich‘s Subway (2010), which placed a sterilized version of New York’s urban transit reality within The Armory Show. It struck an apt contextual note – much like his piece, The Boat, did during Art Basel Miami Beach 2010. Both works form part of Erlich’s video window series and consist of an architectural element combined with video.

For Subway, Erlich sets a life-sized stainless steel door within a wall and positions video as window into a subway car. The video becomes a realistic extension of the architecture and evokes great depth to create the illusion of looking ‘through’ it extending into the distance. Three passengers sit in the immediate car, avoiding eye contact and lost in their own thoughts. The figures are quiet and self-contained much like the video throughout its brief (1 min. 30 sec.) loop. The light changes as the subway bumps and shakes along its track. Renaissance paintings offered a window into another world; in a similar way, Erlich uses the moving image to depict an imagined, realistic 21st century environment.

Last Meal on Death Row 'William Joseph Kitchens' (2010), Courtesy the artist and Blaine|Southern Gallery, London.

The Armory Show: Blain|Southern Gallery

Blain|Southern Gallery in London filled their booth with a selection of work, including Mat Collishaw‘s series of C-prints, Last Meal on Deathrow. In this haunting fact-based series, Collishaw depicts the last meals requested by recently executed American death row inmates. Drawing largely from the state of Texas and Jacquelyn Black’s documentation in Last Meal, Collishaw examines the ritual of eating before execution in a quiet, somber way.

Content is secondary upon first viewing one of these prints. One is initially drawn in by an aesthetically pleasing arrangement of food, silver and glass – all of which was cooked and prepared by the artist. The viewer is lulled by an apparently reticent image before reading the caption and learning of the context. Collishaw’s series is visually inspired by Flemish Baroque still lifes. Such a visual influence is evident in the dark backgrounds and supporting surfaces, which provide contrast for illuminated objects. Just as layered meaning exists within the Baroque still life, the seemingly innocuous prepared food serves to reveal deeper meaning about the societies and individuals they reference.

Trees of 40 Fruit (2009-2011), Sam Van Aken, Photo: Bill Orcutt, Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, NY.

The Armory Show: Ronald Feldman Fine Arts

Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, NY exhibited a solo installation by artist Sam Van Aken featuring his ongoing New Eden project, which filled the booth with vegetation. New Eden features a genetically altered orchard of trees or natural ‘sculptures’ that have been manipulated by the artist and painstakingly grafted to bear peach, plum, nectarine and apricot fruits. Branches of blossoms on each tree indicate the presence of these disparate elements. Part of the installation were synthetic mutations of grafted fruits and a display stand with hybrid vegetable seed starters. Along the walls, prints of mixed seed packets and seed packet collages completed the booth.

While the installation initially seems to emphasize the unexpected aesthetic pleasure of genetic modification, its presence within the gallery space is intended to raise the profile of increasing scientific infringement on the natural world. Van Aken starts a critical dialogue about genetic modification, which he views as futile. As the artist told Art Newspaper ‘any change that you make is temporary’. Mother nature proves stronger in the end and ultimately rejects human interference.

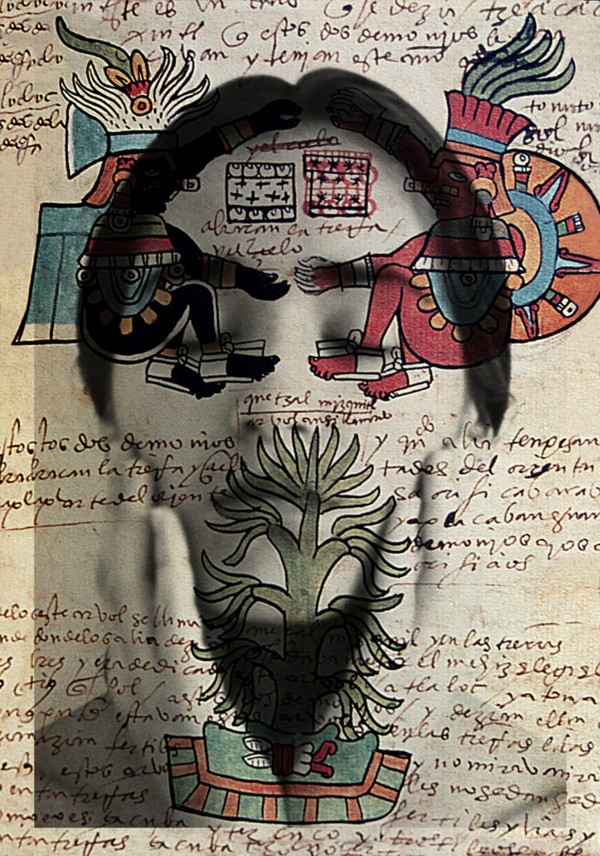

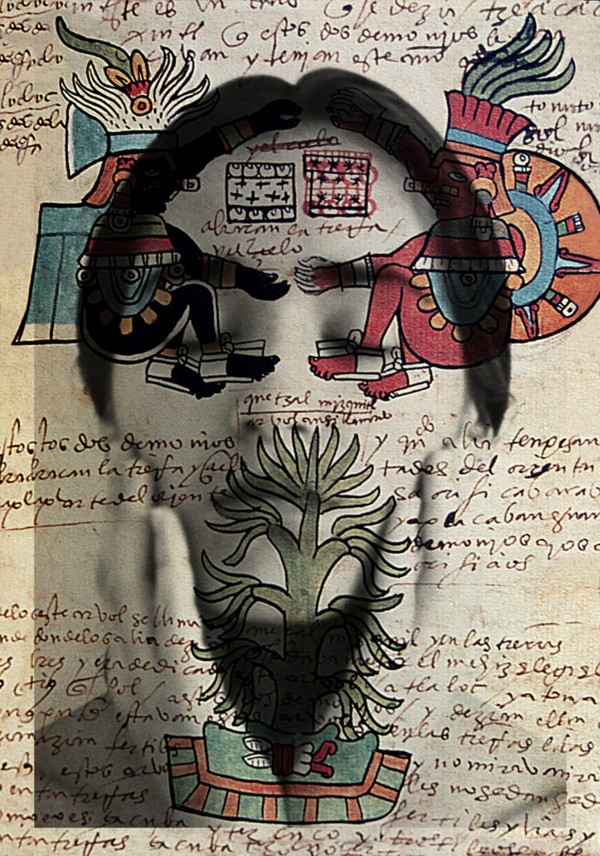

Cartografia Interior # 35, Courtesy the artist and Espaivisor-Visor Gallery.

Volta NY: Espaivisor-Visor Gallery

Espaivisor-Visor Gallery in Valencia, Spain exhibited new and recent work from the series Cartografia Interior by artist Tatiana Parcero. In this series, Parcero redirects the contemporary trend of imagined geographic mapping onto the body in order to position it ‘in relation to time and place, science and thought’ further indicating that the body is ‘the container that holds everything’ including history, culture, and geography.

The ancient images appear like tattoos at first glance, which underscores Parcero’s view that the historical thoughts contained in the images are indelibly linked to the body. The tattoo-like writings and drawings are taken from extensive research. The artist has collected and photographed documents including pre-Columbian codices, ancient maps, cosmological charts, and anatomical engravings. Parcero then printed her findings onto transparent acetate and layered them over intimate, corresponding photographic images of her body. The ancient world and the artist’s own flesh visually bind and are re-imagined as one.

Winter Dreams - Table, courtesy the artist and MA2 Gallery.

Volta NY: MA2 Gallery

MA2 Gallery displayed new and recent work by Ken Matsubara, which was recently part of Winter Dreams, a February solo show at the Tokyo gallery. Matsubara’s Winter Dreams series is defined by his continued exploration of memory as both a collective and personal phenomenon.

MA2 Gallery’s booth was filled with small-scale mixed media works that invited intimate viewing. At first glance, many of the objects could be readily encountered in the everyday world. Purposefully weathered, framed shadow boxes and mirror boxes mysteriously presented moving images of simple motifs. In Winter Dreams – Table, a ghostly, empty table covered by a white table cloth stands alone and spins. Likewise, Winter Dreams – Cloud reveals an emanating cloud of smoke beneath a faded, silvered surface. The artist’s emphasis on mirrors, in the form of aged, reflective surfaces points to the essence of memory as it is formed by the often hazy impression of experiences and dreams on our consciousness. The open-ended nature of the images allowed them to be experienced by many viewers. Finally, in Bottom of Buddha’s Hands, two shiny hands holding a crystal ball connect the concept of memory to humanity’s beginnings.