Gabriel Kuri at the ICA Boston

Hidden within the hard facts are things too complicated and involved to be considered with too much precision. Economists and scientists choose what to measure when running their reports with good reason: if they eliminate the extraneous data than the utility of their predictive models increase.

This process hides what Gabriel Kuri calls “soft information in hard facts.” His sculptures are attempts to reclaim that soft information. Kuri’s pulls from singular sets of materials: advertising spreads, deli tickets, building materials and soap samples. Receipts form the core lexical basis for the exhibition playing roles as temporal markers, financial indicators, relics, and mimetic repositories. The entire show is spasmodic, an irregular and patchy incorporation of numerous bodies of work, but within that chaos are moments of real elegance.

Gabriel Kuri, Recurrence of the sublime, 2003. Bowl, avocados, and newspaper. Dimensions variable. Edition 2 of 3. Courtesy of the artist and kurimanzutto, Mexico City, Photo: John Kennard

One body of work seems to draw equally from the “luxury” condo market and hotel bathrooms. Slabs of countertop materials lean against the walls, attractively conjuring up 70’s minimalism. What distinguishes these from the ghost of minimalism-past are the soap samples placed on top of them. These odd inclusions into the white cube are an example of him releasing his authority to something other than his handiwork. In the past, he has gone so far as to allow for visitors to hang their coats on his sculptures in order to explore the limits of what artists should control.

Gabriel Kuri, Complementary cornice and intervals, 2009. Marble slabs, courtesy cosmetics, 149.5 x 182 x 8 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Franco Noero Gallery, Turin. Photo: John Kennard

His plastic bag amoebas, 2004’s Thank you Clouds, blow around on the ceiling holding nothing. Their bodies are herky-jerky billowing sacs that do not deny their everydayness. Locked down to the ceiling, unable to blow away, their tormented movement is more forced than 2008’s Model for a Victory Parade, a rolling energy drink on a conveyor belt that greets people to the exhibition. While formally simple, these works demand that the viewer engage intensely with the work. This may be Kuri’s central strength and problem. He forces a level of engagement that isn’t always possible outside of a tightly programmed solo show or a catalog with lots of supporting materials. I think that some of the work rewards intense reading, but some do not.

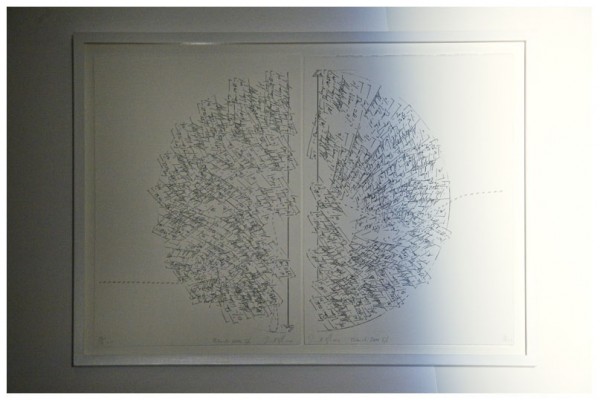

The standouts are his untitled receipts made into handwoven Gobelin tapestry. Following a logical process of buying and ringing up the same objects from the same store three years in a row creates a distinct and conceptually tight readymade. Beyond the work’s rational, these are objects that are awesome. They ooze poise. Same with Trinity. The simplicity permits these works to just be. No wrestling matches with meta-historical, data-constructs, and oblique-historicisms. Just compelling artworks.

Gabriel Kuri, Trinity (Voucher in triplicate), 2006. Three hand-woven wool tapestries. Each 334 x 118 cm. Collection of Gordon Watson, London. Photo: John Kennard

Gabriel Kuri: Nobody needs to know the price of your Saab is at the ICA Boston from Feb through July 4, 2011. It was organized by the Blaffer Art Museum.