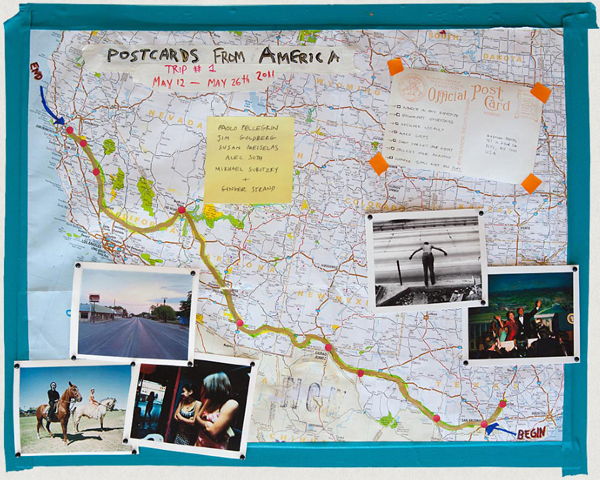

Postcards from America: a New American Road trip

Last Friday, May 13th, at the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas, five Magnum photographers and one writer gathered to kick off their road trip christened, Postcards from America. Paolo Pellegrin, Jim Goldberg, Susan Meiselas, Alec Soth, Mikhael Subotzky & Ginger Strand will spend the next two weeks living together on a bus named “Uncle Jackson,” traveling from San Antonio, Texas to Oakland, California.

Postcards from America is certainly reminiscent of the 1935, Farm Security Administration (FSA), a project part of the New Deal for which photographers like Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange and others, were sent out to document the condition of rural families and areas during the depression. The difference in this contemporary iteration is that it is completely conceived and motivated by the photographers themselves, instead of any government or institution. This crucial characteristic gives the road trip the qualities of a trip with friends, one driven by adventure, curiosity, and the desire to show a side of the US that is often swept under the proverbial rug.

The project originated as an idea by Jim Goldberg and Susan Meiselas at one of Magnum’s annual meetings. In efforts to try to re-establish the way photographers and viewers experience the US, they brainstormed how to “see what America really is instead of just reading about it,” they “wanted to see and feel America.” (Meiselas)

From left to right: Carlos Loret de Mola, Lara Shipley, Ginger Strand, Paolo Pellegrin, Jim Goldberg, Susan Meiselas, Alec Soth, Mikhael Subotzky.

Like most road trips, this one started with a handful unforeseeable set backs (maybe Friday the 13th should have been a day spent in hiding); San Antonio experienced massive flash floods; Jim Goldberg caught the flu; the projectionist at the Ransom Center had technical difficulties during almost the entire panel discussion – but they approached the entire situation with the sense of humor shared between friends, which helped the audience, myself included, laugh along with them and appreciate the spontaneity and organic development of the project. As Alec Soth said on Friday, “the spirit of the road trip is you let it take you.”

Paolo Pellegrin, San Antonio, TX

While the projector was being fixed, each photographer and the writer, Ginger Strand, introduced him or herself by talking about their approach to the trip and what they had already experienced the day before in San Antonio. Each individual set off in search of something, and the amount of incredible material, images and stories they encountered in just one day was astounding. Once we saw images from the day before, it was clear that the project will reveal a truly diverse view of the US.

Alec Soth, Mu Man from Burma, San Antonio, TX

The Postcards from America project will conclude with a pop-up show at the Starline Social Club in Oakland, Ca on May 26th. For more information, check out the Postcards from America site to track the group on their journey, through their blog, twitter and facebook updates.