Nomadic and Luminous: Ranu Mukherjee at Frey Norris

Ranu Mukherjee, Auspicious Picture, Multiple Sources of Power (2011). Hybrid film, 2 minutes 51 seconds. Edition of 5. Image courtesy of the artist and Frey Norris Contemporary & Modern.

What happens at the moment when energy becomes material, and how can we even dream of documenting it? The question has wide-ranging implications, from the memories stored in everyday objects to the effects of prayer. Ranu Mukherjee’s solo exhibition at Frey Norris Contemporary and Modern, Absorption Into the Nomadic and Luminous, takes up these issues. A former painter who now works mostly with photography and animation, the question has particular potency for Mukherjee, as it references the creation cycle of a painting (from pigment to paint to image), the balance between the intangible and tangible found in digital video, and perhaps the link between.

Ranu Mukherjee, Rajasthani Gypsy Shoes, Dr. Gabrielle Francis (2011). Ink on colored paper. 19 5/8 x 19 5/8 in. Image courtesy of the artist and Frey Norris Contemporary & Modern.

Nomadic and Luminous consists of a series of square paintings and a suite of hybrid films (so-called due to their combination of animation, photography, and video). In the first film, Auspicious Picture, Multiple Sources of Power (2011), an animated emanation, or halo, glows above a live action shot of ocean waves at night. As the emanation fades and disappears, different articles of clothing and tapestry appear and disappear in the foreground, almost dancing, and we are left to contemplate each object—ocean, emanation, and clothing—as a source of power in its own right.

Ranu Mukherjee, Between the no longer and the not yet (2011). Ink on colored paper. 19 5/8 x 19 5/8 in. Image courtesy of the artist and Frey Norris Contemporary & Modern.

The second film, Abundance Picture, As Told By the Element Itself (2011), opens with the image of a checkered-cloth bundle making its way across a crocodile-filled river, with children’s silhouettes in the background. After a while the silhouettes fade, and the next image features bright clothing hung from tree roots, juxtaposed against a hand-painted landscape as yet another shadowy silhouette moves in and out of the frame, eventually revealing itself to be pile of gold. The final film, Ecstatic Picture, Spilled Milk (2011), shows the infiltration and spread of a pitcher of spilled milk amongst a constant rain of flowers, Indian clothing and jewelry, and other objects. The empty silhouette of what could be a deity, or perhaps a mother and child, occupies the center of the screen. Eventually, a mass of cell phones appear and pour forth the rainbow equivalent of spilled milk, which mingles with rest of the animations and references the boon that cell phone technology has brought to India.

Ranu Mukherjee, Ecstatic Picture, Spilled Milk (2011). Hybrid Film, 5 minutes 4 seconds. Edition of 5. Image courtesy of the artist and Frey Norris Contemporary & Modern.

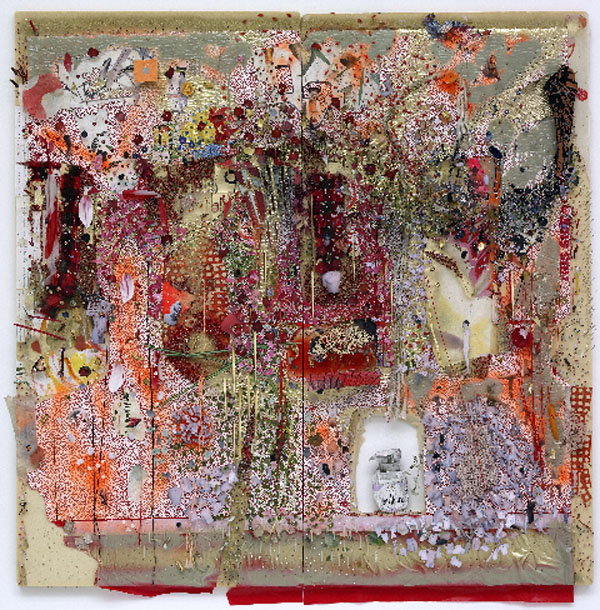

Taken together, the films provide a meditation on tangibility and intangibility; landscape, negative space, and sacred space; void, object, memory, and isolation. And while Mukherjee describes the accompanying paintings as merely “note taking,” they should not be undervalued—particularly because they provide us with Mukherjee’s lexicon. The same pair of gold Rajasthani gypsy shoes, with their curled toes and red interiors, for instance, appears in both Rajasthani Gypsy Shoes, Dr. Gabrielle Francis (2011), and Auspicious Picture (2011). Similarly, landscape fragments based on lithographs of Indian deities, with the deities cut out, show up in multiple paintings, as well as both Auspicious and Ecstatic Pictures.

Ranu Mukherjee, Abundance picture, as told by the element itself (2011). Hybrid Film. 3 minutes 32 seconds. Edition of 5. Image courtesy of the artist and Frey Norris Contemporary & Modern.

To Mukherjee’s credit, the work never becomes ponderous, but remains uniquely well-thought out and mesmerizing. On a more personal note, the objects in the paintings also reference Mukherjee’s Indian heritage—just one more way long-stored energy materializes or becomes current.

Absorption Into the Nomadic and Luminous is on view at Frey Norris in San Francisco through July 30, 2011.