The natural tendency, when attending a show that promises to give you a sampling of a locale, is to define that culture through the exhibition’s cohesion. With everyone in Berlin identifying as an artist (a little hyperbolic), the saturation leads to a lot of “bad” art and “good” art, however you personally define it, making pinning down what is vital in the art world here an impossible task, and with over 80 participating artists, the multi-venue Based in Berlin seemed dead on projecting the art scene as undefinable, multicultural, and all-encompassing.

Oliver Laric, CEO (Installation shot), 2011, Courtesy of Based in Berlin

The international image of Berlin is nowhere more visible than in the city’s restaurant industry. Eat-in restaurants commonly seem to lack a speciality in-lieu of offering upwards of 200 items from around the globe; Mexican, Chinese, Japanese, American and of course traditional German all in one spot. Supply constraints, because of kitchen economics and Berlin’s geographic location limit ingredient availability and often result in diluted and deluded versions of what should be. Because they try to replicate several foreign cultures all at once, these restaurants produce nothing authentically. It’s as if they have all the recipes, but substitute readily available ingredients for the harder to find items.

Is that what Berlin culture at-large has become: other cultures with Germany filling in the blanks when necessary? Surely one should be able to look to the community’s art to be at least representative of the culture, if not be the culture. Berlin’s reputation for art itself has led to this continual migration of artists searching for something in the city to aid in their process (whether it’s cheap rent, inspiration, connections, etc.). The result may mean learning from mentors that were new immigrants themselves no more than five years ago. Looking at the biographies of the artists presented here, most are foreign born, few are from Germany, and fewer still call Berlin their hometown. It’s as if there was a big empty space where all of the artists just decided to meet up, and in some utopian fantasy dreamed up the Berlin art scene… almost. Without responding to the city itself, artists are left trying to find their identity through something that can’t be defined. The focus here seems to be not on embedding oneself in a culture, but instead being one who helps define it.

Erik Bünger, The Allens, 2004, Video installation, Courtesy the artist, Photo: Erik Bünger

Pieces like Erik Bünger’s The Allens, 2004, illustrate this image of Berlin. Putting on the headphones and listening to Woody Allen give a monologue, every next word translated into another language, is much like navigating the city. It’s impossible to follow all of the conversations, but hearing the variety of languages is inescapable. All of these cultures are being filtered through one figurehead, one of the most imitated and parodied celebrities in Western culture. Allen iconic voice and way of talking is stripped away as the words are spit out inorganically to reassemble the original text, leaving only glimmers of the original English speech.

Because, by and large, the artists are at least somewhat outsiders, is this show just a coincidental collection of work that could have just as easily been ‘The Studio Complex Group Show’ on 123 Fake St. in Anytown, Earth? The pitfall with defining one’s own culture in a white cube called Berlin, is that it makes culture, by negating Berlin’s entire history, irrelevant, and thus makes any attempts at cultural creation also irrelevant. When there is no real focus on preservation of local culture in the contemporary art of a place with hundreds of years of internationally impacting history, artists create their own problems instead of dealing with the problems already present in society. Moving to Berlin changes to moving to any foreign land and dealing with a new life situation. Understanding one’s existence in Berlin, with reference to the historical boundaries, navigational limits and cultural differences between adjacent neighbourhoods becomes understanding one’s existence in either a global sense, or a completely personal sense. It makes me wonder to what extent the art community in Berlin speaks to the multi-generational locals, or if there are two co-existent but mutually exclusive culture systems in Berlin.

Matthias Fritsch, Replace:Technoviking, 2011, Video still, Copyleft by, Courtesy of the artist

Matthias Fritsch’s We, Technoviking, 2011, a video that is situated partly at Berlin’s Fuckparade, manages to drift between the local and the global. The original footage named Kneecam No.1, a popular internet meme, is both silly and startling; the technoviking is serious about fun, and protection. Social order is maintained by this super hero-type figure in what one would expect to be a festival that seems almost created to get out of hand. We, Technoviking compiles Youtube posted response videos inspired by the technoviking video and blurs the line between what is unique to Berlin and what is common around the world. The incredible international popularity of the footage has inspired an archive and exhibition that decentralizes the original event and relocates it in college dormitories, parks, and anywhere else. The nature of this video questions the authenticity of the event itself; no longer a unique experience in time and place. Everything is everywhere, there is no here.

Critiquing consumption may have been one of the bigger trends at Based in Berlin this year. Certainly, it’s something that most of us in industrialized society have conflicting feelings about. While I guess it’s nice to know that artists here are thinking about it, pieces like Rocco Berger’s Oil Painting, 2010, would have read the same in any Western star city and doesn’t benefit from being placed in a show that presumably wants to link the artists and city through the cultural production of art.

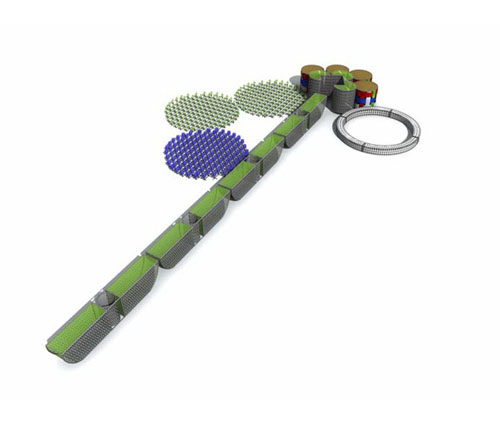

Rocco Berger, Wir müssen ins Detail gehen, 2009, Motoren, Holz ,Förderband (recycled), Galerie Alte Schule

It’s hard, as an outsider without local knowledge, to comment on Berlin’s body social with any sort of reference for local culture in Berlin. Instead it’s the popular culture that provides a skimming/surveying of what Berlin is with information that is at this point cliche (namely regarding Nazism and The Wall). Only the simplified, tourist-version to what are extremely complicated issues is accessible and therefore may get overlooked in-lieu of pursuing more self-centered subject matter. At its worst, it’s taking what the artist inherently has as the base of the meal, shaking in a few splashes of Wurze, and calling it Berliner art, and may be rightly feared by the immigrant artist. But this ignorance of the local is what is continually obfuscating the culture further and pushing it evermore so out of reach. As artists continue to produce with focus on the personal and the global, lack of identity becomes identity. Berlin may not be the only city faced with this issue, but it seems to be a brilliant example of the results of urban gentrification.

This discussion exists for me in Oliver Laric’s installation, CEO, 2011. One must climb up a temporary structure to view three SUVs sitting on a constructed roof with a vantage of some of the most iconic buildings of Berlin. At once it discusses global concerns of corporatism, consumption, waste and the environment, and contextualizes it amongst the history of the city. It addresses the disconnect between our daily lives and feeling any sort of connection to the locale beyond the personal. While the focus on multiculturalism and globalization may be positive directives at times, local culture and values still exist in large cities and continue to inform the cultural production of places like Berlin. By art culture diverging from Berlin’s local culture, two separate cities will form within one space, and art will further obscure itself from general society. Without local knowledge, opinion and input, any attempt at producing an authentic culture will come off tasting like a kidney bean burrito.