Matrix 162- Shaun Gladwell

An athletic international globe-trotter, Shaun Gladwell‘s first solo show in the US is Matrix 162 at the Wadsworth Atheneum. The exhibition is of five videos (2005 through 2010) and one still image from a video. It ends up reading as a sort of mini-retrospective. It brings together work from his early preoccupation with extreme sports and urban motion through his reflection on the Mad Max movies (shown at the 2009 Venice Biennale). His post-Venice works are distinctive, including themes found throughout his career with a new-found subtlety.

Yokohama Linework from 2005 is a point-of-view video (here projected on the floor) of a skateboard traveling through Yokohama. The line he traces through the city is like an abstract drawing. It’s a linear composition with no narrative, an urban outline functioning as a self-portrait. He alludes to his own personal interests outside of art in this and other early videos, creating a caricature of the internationally wandering extreme athlete.

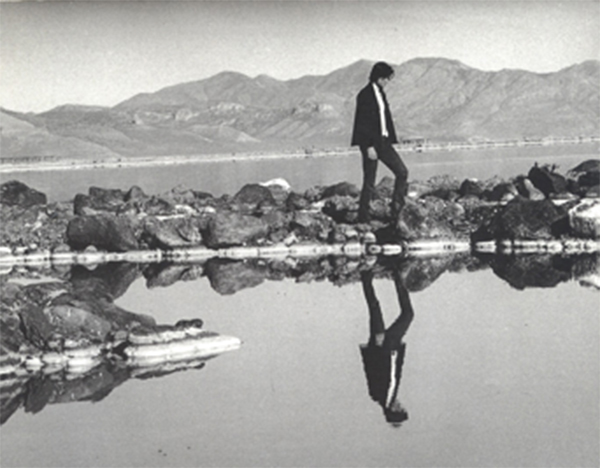

Anytime an artist brings in their own hobbies, it seems we then have to call it a form of pop art. Gladwell does directly engage popular movies in his MADDESTMAXIMVS series (2005-2009). After recreating Max’s Interceptor, he filmed two almost identical videos of an black-clad anonymous outlaw surfing on the top of the moving car. These two parts of Surf Sequence, one shot on a clear day and the other in front of a storm, were filmed in slow-motion, elongating the activity and emphasizing the surrounding landscape. This leads the audience to consider both the action and the surrounding Australian landscape.

There is a remarkably different feeling in his Apologies 1-6. Instead of being the outlaw engaged in risky behavior seemingly for fun, the outlaw now is following truckers in the outback of Australia, removing and caressing the resulting roadkill. The kangaroos that he picks up immediately echo Joseph Beuys’s How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, but there is an additional layer here in that he is still portraying his Mad Max character. Is there a soft-side, an empathetic and socially liberal message in Mad Max that I don’t remember? The outlaw in Gladwell’s Apologies is an almost mushy, a gently affectionate human who spends time caring for these dead animals that have fallen at man’s mercenary hands.

Gladwell is presumably carving out a space for the extreme sports enthusiast to have these feelings. Instead of just being a reactionary, everlasting man-child, Gladwell inserts an adult concern into this video game character stereotype. It would be impossible to simultaneously be a thinking person and a slave to the x-games formula of masculinity. Gladwell’s video still of a soldier balancing his gun on his hand allows another inquiry into masculinity. The pigeonholed roughneck is shown in a more casual playful note. Instead of considering the scars left behind by war, in the manner of Sophie Ristelhueber, Gladwell is offering up a quiet moment of humanity that looks foreign as a soldier.

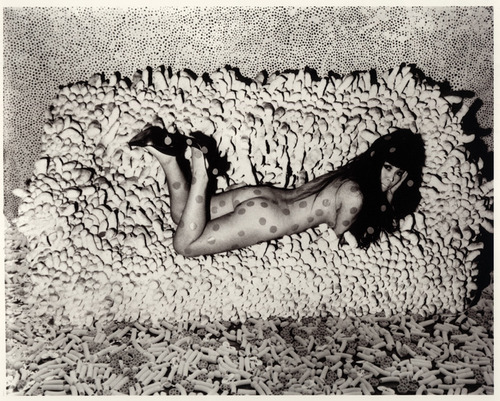

The gun in this film still is similar to the prosthetic devices (skateboard, stilts, and crutches) in a trio of videos culled from his Pataphysical suite. These images of humans using tools to spin returns to his interest in extreme sports, but instead of placing the artist at center, he films hired performers to enact these physical actions.

His most most recent video on display, Pacific Undertow Sequence (Bondi) brings all these themes together. Gladwell sits on a surfboard, but something looks strange about this. What’s going on is that he is upside down, the sun is below him; the light is coming from the bottom to top, he has to lean down to get air, and the waves we see crashing are the undertow of each wave. Gladwell is engaged with an extreme sport again, but instead of being macho and powerful master of improbable motion, he is at the impulses of the tide. Underwater, unable to breath freely, his athleticism keeps him alive. There is another subtle symmetrical landscape with another single actor. Present again is his connection to the outdoors but it doesn’t function on a literal level, have a pedantic message to get across, or refer to a single device. It’s more physical and powerful than conceptual. Trying to sit still on a surf board might be his most vigorous work yet and his most understated.

Matrix 162, Shaun Gladwell is on display at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford CT from June 2- September 18, 2011