All Artists are Punks…or Hippies

L.A. Expanded: Notes from the West Coast

A weekly column by Catherine Wagley

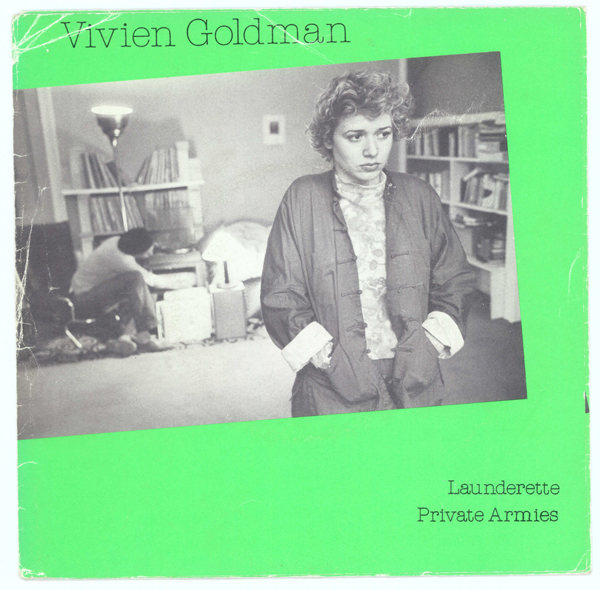

On Saturday, July 16, Honor Fraser Gallery in Culver City hosted a panel on Punk. The panel preceded the openings of two shows, one an earnest exploration into punk’s visual precedents and antecedents, and the other an extravaganza of posters, bills, and graphics from the Punk movement of 1970s Britain. The Punk panel, chaired by Vivien Goldman, who has been a writer, performer, scholar and manager—she’s recently written a book on reggae—included a surprise guest who came in and put his motorcycle helmet on his chair about ten minutes after the panel’s scheduled start time.

Linder, "Pretty Girl I 1977/2006," Pigment print of original artwork, 7 x 9 2/5 inches, Edition 1 of 5. Courtesy Honor Fraser.

This surprise guest was Billy Idol, one of the more accessible of the punk rockers who started out in Britain’s scene. He had his signature leather, sunglasses and spikey hair, and, when the panel finally started, a lady in the front row went on to take a good few hundred photographs of him. A few others were making cell phone videos. But the woman next to me, chicly dressed and probably in her sixties, handed me a paper and asked if I could please write down the name of the man with the sunglasses so she could remember.

Billy Idol does not qualify as obscure, but many of the bands whose posters are plastered to the walls of Honor Fraser—the Slits, for instance—remain utterly unknown in certain circles. But their provocateur posture and moody DIY aesthetic will, I assume, strike most in the Western world as familiar.

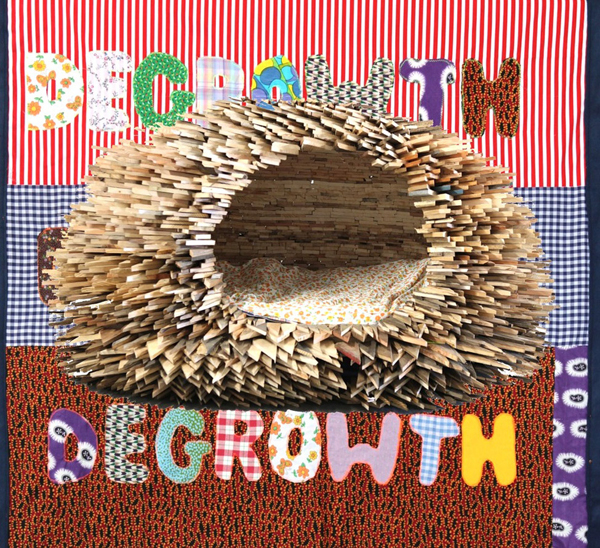

A professor I had in grad school used to say all artists are either punks or hippies. My classmates and I spent a lot of time picking out who was who, and it’s harder than it sounds. Are you a hippie just because you use organic shapes and found materials? And are punks more defiant and streamlined? Can you be a concise hippie? Can you be an earthy punk?

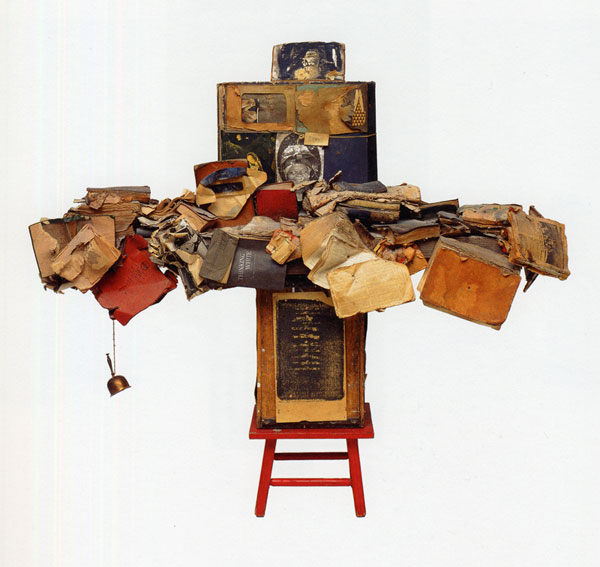

A show that brings hippies and punks together in a concert of dissonant materials is the George Herms: Xenophilia (Love of the Unknown) exhibition that just opened at MOCA. Herms, a California artist who came up with no-holds-barred assemblage artist Ed Kienholz in the 1960s, has always had a slightly more elegant approach to gritty found object sculpture than his burly peer. The MOCA show puts some his early and later works into conversation with a number of 21st century artists, among them Amanda Ross Ho, Kaari Upson, Sterling Ruby and Elliott Hundley. Upson and Ruby are definitely punk; the blatant way they use ceramics and plastics feels insidious, unapologetic and almost dirty. Hundley is a hippie. His hanging sculpture is too organic and comfortable with itself. It has no bone to pick, but it’s painfully self-aware. Others, I can’t quite tell. What about the sprawling canvas made by Dan Colen, Agathe Snow and friends that looks like Sam Francis’ take on Warhol’s flowers? Even Ross Ho’s haphazard installation has a hippy-like mood, but a punk resistance to having meaning’s imposed on it. Whichever it is, the Herms show really does have a great, nonsensically collaborative mood to it, and I highly recommend a visit.