Grounds for Annulment

L.A. Expanded: Notes from the West Coast

A weekly column by Catherine Wagley

Jeff Wall, "The Destroyed Room," 1978, Transparency in lightbox, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. © The artist. Discussed in Michael Fried's book.

When essayist Geoff Dyer, whose main goal always seems to be sating his own curiosity, debuted his New York Times book column last week, he did so with a perfectly paced takedown of art historian Michael Fried. Fried famously “exposed” the melodrama of minimalism in the late 1960s, and that’s what he remained known for until he discovered something new a few years ago: photography. The book that heralds this discovery, Why Photography Matters as Art as Never Before, argues the photograph has moved from the valleys to the precipice of contemporary art. It has become cutting edge, and artists like Jeff Wall and Thomas Struth are among its edgiest practitioners.

Why Photography Matters spends a lot of time reflecting on its author’s own critical legacy, announcing the relationship between Fried’s current and previous thinking and making sure readers know exactly which argument the book is about to make before said argument is made. It’s this preemptive announcement-making approach that Dyer dug into, caricaturing Fried’s tone, and ending by saying, bitingly, that someday Fried “will cross the border from criticism to the creation of a real work of art. . . called Kiss Marks on the Mirror: Why Michael Fried Matters as a Writer Even More Than He Did Before.”

I loved Dyer’s column the first, second and third time I read it. Then, a few days after it appeared, I came across this tweet by @bobbybaird (a.k.a. Robert Baird, a Chicago writer): “Dyer’s a great mimic, but I’ve never understood the urge to make reviewees seem less interesting than they are.” The tweet made me feel slightly embarrassed. Swept up by Dyer’s deft parody, I’d overlooked what the column downplayed: that, pompousness aside, Fried’s perpetual self-announcement has led to some pretty memorable criticism. And he made seemingly paradoxical ideas about the indulgences of pared-down art like Donal Judd’s or Carl Andre’s easier for me to articulate on my own. I keep a copy of his 1967 essay, “Art and Objecthood,” in my desk drawer.

"Piero Golia: Concrete Cakes and Constellation Paintings," 2011, installation view. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills. Photo: Douglas M. Parker Studio.

It’s hard to be incisively critical and fair at the same time. It’s definitely possible, though. Zadie Smith, a writer I often associate with Dyer perhaps because she’s his outspoken fan, became a book columnist for Harper’s nearly a year ago. Her inaugural column considered Harlem is Nowhere, a debut essay collection by the young Sharifa Rhodes-Pitts. The book’s dreaminess annoyed Smith, and a friend who read the first draft of her review called it contemptuous. The same friend made a suggestion: “come to Harlem and see what she means.” Smith went, and spent a day experiencing Harlem the way she imagined Rhodes-Pitts must have. Then she read the book again. The review that appeared in Harper’s had some reservations but no contempt. “This dreamy atmosphere [Rhodes-Pitts] was trying to conjure up is something real,” Smith said in an interview with Harper’s editor Gemma Sief. “My first reaction to it was in actual fact wrong.”

There’s a place in the world for fast-paced, acerbic criticism. But giving yourself the time to think and, when necessary, double back on your ideas? Far richer in the long term. That said, criticism can be cruelly difficult if you try to meet each work on its own terms, in the visual arts at least as much as in literature. Guys like John Ruskin, who celebrated the Pre-Raphaelites and hated on James McNeill Whistler in 1840s-70s England, or Clement Greenberg, who crusaded for abstraction in 1940s-70s New York, found a way to side-step some of that difficulty: they built up their own value system and moved through the world more or less championing what fit the system and rejecting what didn’t. The efficacy of such dogmatism seems to be waning a bit, however. The writers I trust most speak their minds but readily admit their minds can, or maybe even should, change.

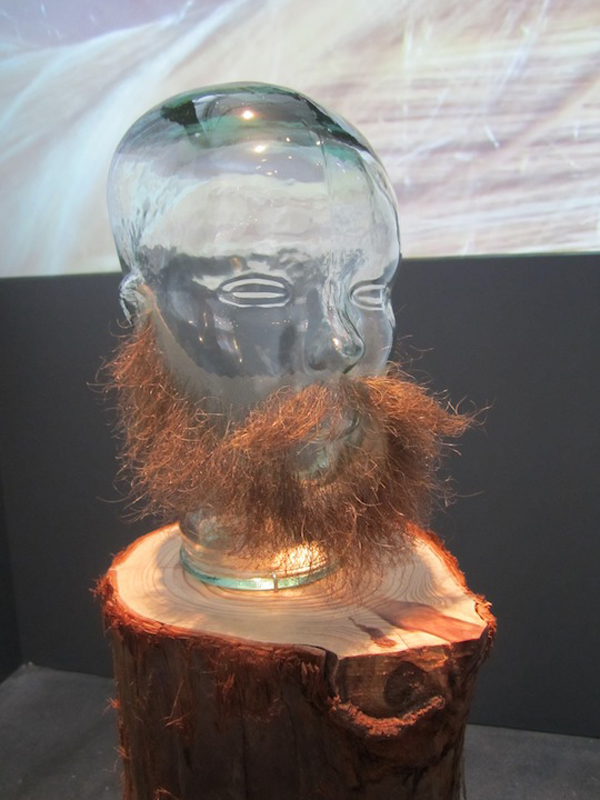

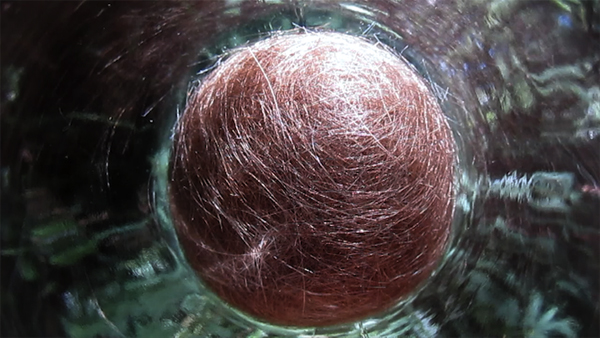

Writer and curator Ed Schad has an L.A. blog, icallitoranges, that takes itself and its subjects seriously; there’s often some sweat and blood behind its posts. Two weeks ago, Schad grappled with artist Piero Golia’s exhibition at Gagosian’s Beverly Hills space, posting a review of the artist’s concrete cakes and debris-covered paintings, and questioning whether the art lived up to the artist’s ideas. I read the post the morning it went live, and appreciated its self-awareness. However, by mid-day, the review had disappeared. Schad gave no explicit reason for this, but said that, in a week or so, after further consideration, he would repost.

This past Monday, the review indeed reappeared in its original form. This time, it was accompanied by an account of a three-hour conversation between the writer and artist, initiated, I assume, after Golia read what Schad originally wrote. The two sat on the fire escape behind Gagosian’s Beverly Hills space and tried to understand each other. They didn’t succeed entirely. While Golia set out the terms behind the work in the current show, and Schad tried to wrap his head around them, the critic still ended up dubious. “It is possible that I just don’t get it (very possible),” writes Schad, “but it is also possible that there is something weak going on here, a game of shadows. . . that doesn’t need me, the viewer, to be played.”

"The Rape of Persephone," 1943, Oil on canvas. Both courtesy the Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College. The paintings appeared in the 1947 Federation show.

Years ago, in 1943, New York Times critic Edward Alden Jewell admitted to being “befuddled” and “non-plussed” by the abstraction he’d seen at a recent Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors show. With some help from Barnett Newman, painters Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb, all of whom appeared in the show, responded to Alden, sending a letter to the Times:

It is . . . an event when the worm turns and the critic of the TIMES quietly yet publicly confesses his “befuddlement”, that he is “non-plussed” before our pictures at the Federation Show. We salute this honest, we might say cordial reaction towards our “obscure” paintings, for in other critical quarters we seem to have created a bedlam of hysteria. And we appreciate the gracious opportunity that is being offered us to present our views.

The artists didn’t explain their paintings—that wasn’t their aim, they said—but they put some effort into describing their general beliefs about art. For critics and the public, art’s “explanation must come out of a consummated experience between picture and onlooker,” they wrote. “And in art, as in marriage, lack of consummation is ground for annulment.” Of course, genuine engagement rarely requires a three hour conversation with an artist and not all consummated marriages work out. But annulment seems like the cheap out. Divorce at least means you made a go at it. Then there are those rare married couples who keep at one another’s throats for decades and somehow still manage to make the battle seem worth it.