This Sunday we’re taking a look back at the exhibition, Infinity, curated by Andrew Schoultz in 2009. Schoultz’s own work is currently featured with Paul Klee in the exhibit, Images in Dialogue, on view at the SF MoMA until January 2012.

The following article was originally published on October 23, 2009 by Edy Pickens.

Infinity, curated by Andrew Schoultz is a collection of 15 contemporary artists’ interpretations of a boundless theme. Scion Space in Los Angeles hosts the exhibit, which opened Saturday, October 10th, and will continue through November 7th, 2009. Prior to the opening, I chatted with some of the artists as well as the curator, who revealed how relative concepts are strategically woven into the pieces, whether through mathematics, metaphor, science, or technique.

Schoultz chose artists who frequently question life’s immeasurability, like Ryan Wallace. During the process of completing oil paintings such as Fulcrum, Wallace explained that he saves pieces of tape used to mask off sharp-edges. Wallace then uses the tape and other appropriate odds and ends in his studio to make pieces like Quest. Throughout his process, Wallace experiments with how variables involved in the chemistry of oils, alkyds, acrylics, mylar, paper, and tape affect the surface of his painting. He enjoys “letting each material have its own voice based on chemical properties.” Further, his imagery questions aspects of physics that might be in play. For example, Fulcrum features two intersecting walls; yet, one cannot determine which wall is acting as the support for the other. Therefore, the walls take on an endless “push-pull” scenario. Similarly, Quest features a central orb created by light tones in the center of the panel surrounded by darker vertical strips. The sphere-like shape hovers and can be seen as an ascending or descending point simultaneously.

Chris Natrop scrutinizes the concept of infinity on a more microscopic level in that he thinks of his cut out shapes as “molecular bombardments.” Infinity features one of Natrop’s first, stand-alone sculptures, different from the room-sized installation pieces he is used to creating. In all of Natrop’s work, he deals with shapes that he has captured from his memory–spindling, interweaving forms he spontaneously cuts with a knife and hangs with transparent string. Also new to his work is the inclusion of two-way, acrylic mirrors that he had fabricated specifically for the piece displayed at Scion.

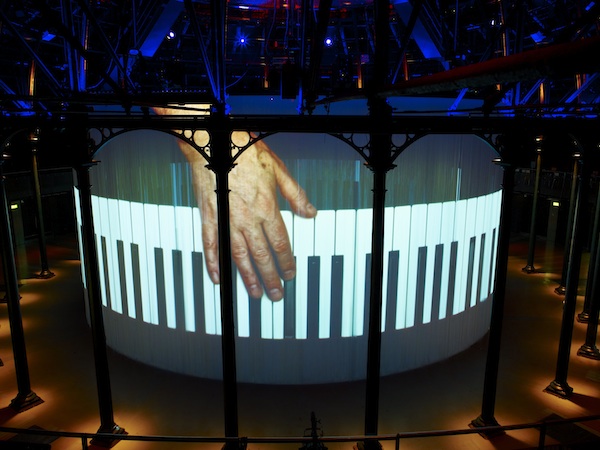

Contemporary collage artist, Hilary Pecis, is represented in the show by two of her collages. One of her works were created specifically for Infinity, as well as some of her new video installations. Pecis’s collages stay true to her fundamental aesthetics. She continues to entrance viewers with meticulous depictions of angular patterns, whether they are the varying facets of cut gemstones or the repetitive planes of her trademark ink drawings. Pecis pointed out the underlying theme of “limitless combinations” in her work. For example, she sought out multiple sources to represent white in her new collage. In the past, she may have used a single source, like fabric from a wedding dress, to fill the white spaces. Now, however, she has substituted many different magazine images in addition to other white fabrics. As usual, Pecis depicts cosmic landscapes brimming with glimpses of society’s prized commodities. She reiterated that the landscapes are basically the same place, but the seasons are different. Seasons change in her work due to the fact that the countless magazines she uses change intervals from spring, summer, fall or winter. Pecis admitted that her reliance on print media will likely shift as digital media becomes more relevant. Her video installations feature segments of her multi-faceted ink drawings interspersed with translucent, floating, shapes, some of them different types of diamonds. In one of the videos, crows horde a pile of diamonds, CD’s, and other “bling”–metaphorically showing that the “continuum of desire is never fulfilled.”

In addition to curating the show, Schoultz contributed an intricate ink drawing that speaks to “the infinite unraveling of history.” The drawing, which is reminiscent of both Indian miniature painting and 14th century German map-making, is chock full of military symbolism. The upper half of the composition is dominated by a labyrinthine mixture of vertical flags, all emblazoned with the masonic eye, and a variety of unraveling ribbons, culminating into the shape of a horizontal 8–the undeniable symbol of infinity. The lower half of the composition shows a military horse carrying a turban-clad man with his eyes closed and hands raised as if in meditation. To Schoultz, it is important to portray the duality involved, so there are references to peace as well as war, just as the infinite must also contain the finite.

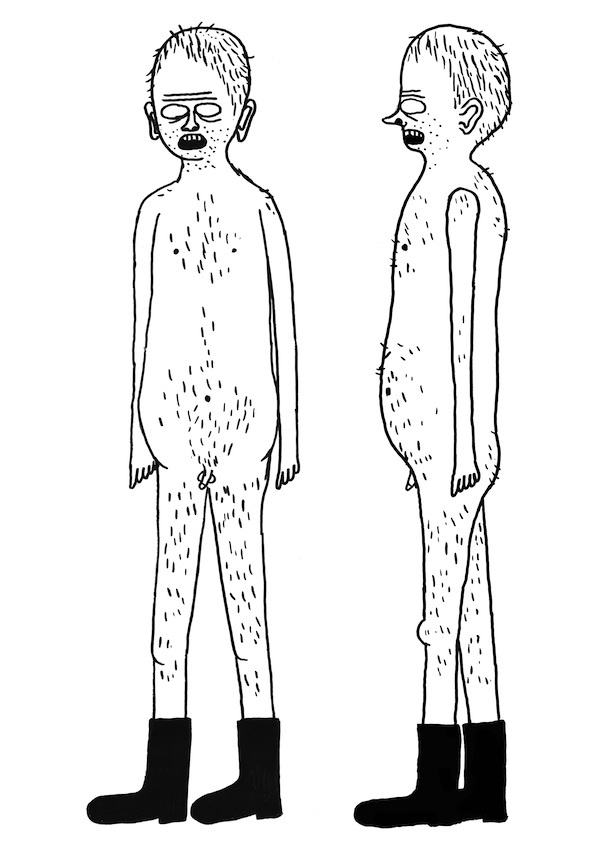

Other artists who participate in the show are Ryan Travis Christian, Richard Colman, N. Dash, Noah Davis, Chris Duncan, Andres Guerrero, Joseph Hart, Andy Diaz Hope, Xylor Jane, Butt Johnson, and Aaron Noble.