On view from September 8 – October 22 at Gagosian Gallery (London), Mike Kelley continues his investigation on the inconsistencies in the story of Superman. Kelley began his quest in 1999 with the Kandors series, and the newest iteration, Exploded Fortress of Solitude, highlights the devastation and destruction of Superman’s home planet.

The following article was originally posted on February 2, 2011 by Caitlin Moore.

Mike Kelley claims he doesn’t particularly like Superman. The jury is out on whether or not this qualifies him as a communist, but his claim does provide a source of perplexity when evaluating the inspiration for his ongoing Kandor sculpture and installation series – the newest of which being currently displayed at Gagosian Gallery (Beverly Hills) alongside the latest chapters of his filmic project, Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction (EAPR).

Kandor 10 / Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction #34 and Kandor 12 / Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction #35, installation view. Photo by Fredrik Nilsen. Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery.

In its original graphic incarnation, Kandor is noted as the fictional capital city of Superman’s native planet, Krypton. By the swift and conniving hands of the villainous Brainiac, the city was taken hostage and miniaturized for purposes not entirely sensible or mildly coherent – but not without valorous retrieval by our hero. Despite Superman’s Samaritan ways, the omnipresent plague of a haunting past hinders him from true emotional and psychological liberation – not to mention, visible underpants. For Kelley, the conceptual appeal lies in Kandor’s embodiment of an alienating victim culture for our protagonist: the notion of a burdensome present dictated by a labyrinthine past. Kelley’s unorthodox fusion of fragmented narrative, medium and sensory immersion seem nonsensical and queer at first encounter, yet the further we delve into his sensational rabbit hole, the closer we come to the truly bizarre fidelity of the human condition. Kelley confronts our latent attitudes and popular convictions relating to sexuality, socioeconomics, education and history with jocular finesse and – well – candor.

Kandor 10 / Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction #34 and Kandor 12 / Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction #35, installation view. Photo by Fredrik Nilsen. Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery.

Like glowing orbs, a handful of Kandor sculptures pepper the multiple galleries within the darkened Gagosian megaplex. The dwarfed cities encased beneath colorful bell jars appear relic-like, yet also profane at times – their jutting skyscrapers evoking a curiosity born of both estrangement and familiarity. The two primary microcosms – Kandor 10 and Kandor 12 – bear oversized tubes that snake into tanks of (presumably) atmosphere, per the accuracy of the comic book reference. Each is situated within environmental installations that embellish upon two distinct anecdotes central to the exhibition: the carnal Moroccan harem featured in EAPR #34, and the bleak sooty chamber that appears in EAPR #35. In merging his previously autonomous Kandor and EAPR projects, Kelley suggests an innate relationship between our own respective microcosmic realities and subsequent conditional behavior.

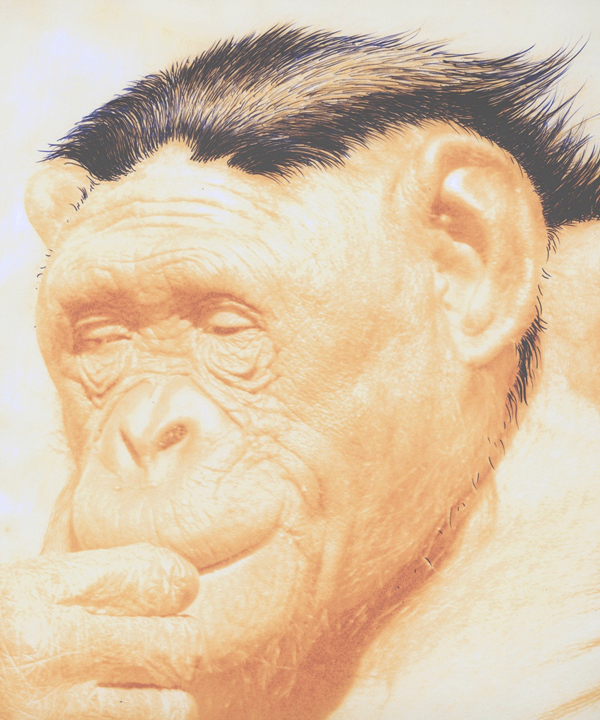

Mike Kelley, video production still from Extracurricular Projective Reconstruction #34, 2010. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery and Kelley Studio.

By way of illustration, Kelley’s EAPR #34 videos largely examine the lascivious conduct of society’s upper echelon when handed unrestricted power and entitlement. Directed in the style of a maladroit stage play, EAPR #34 shifts between a piggish male King belittling his covetous female harem and a group of scornful Queens admonishing a male servant. In both scenarios, the authoritarian’s disposition to abuse of influence and insatiable gluttony bespeaks a cyclical global history of flawed paradigm and deep-rooted desire for accumulation. Beside the video installation, Kandor 10 is nestled within a life-size stony grotto reminiscent of EAPR #34’s exotic Moroccan setting, as if displaying the incubator in which these voracious human mannerisms were nurtured. When the Kandor’s luminous mini-cityscape appears more familiar than it does foreign, one can only muse on how fictitiously reconstructive Kelley’s staged milieu really is.

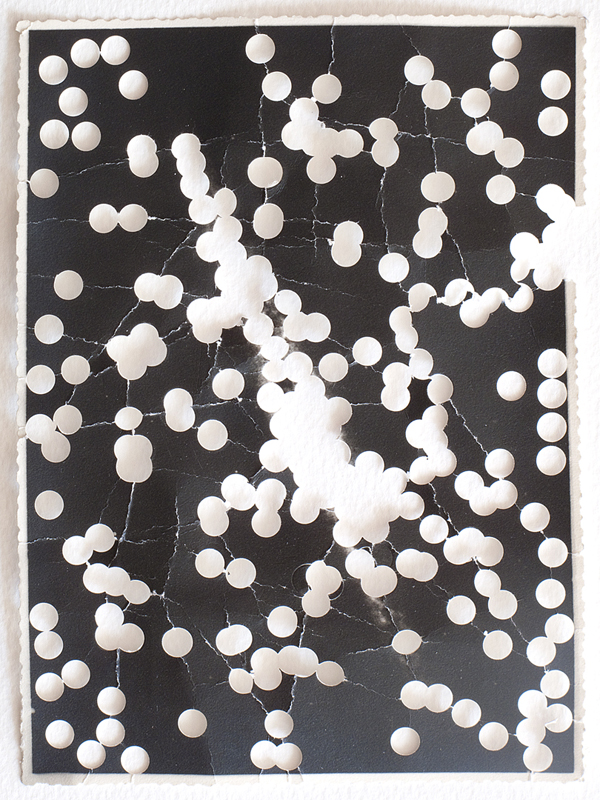

Kandor 12 A (green screen), 2010. Tinted Urethane resin, steel, blown glass with water-based resin coating wood, enamel paint, silicone rubber, acrylic paint, lighting fixture and Lenticular 12. 126 x 202 x 276 inches overall (320 x 513.1 x 701 cm). Photo by Fredrik Nilsen. Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery.

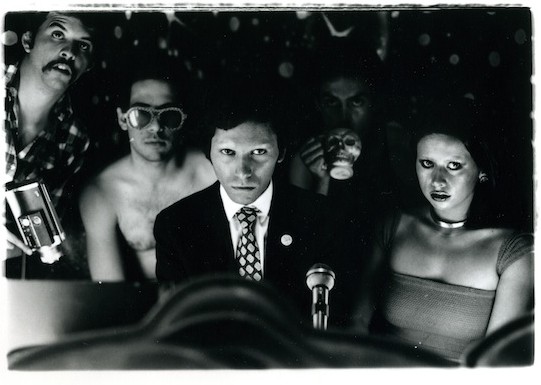

Conversely, EAPR #35 jettisons us into a place of somber isolation and denial. Grimy clownish gnomes aimlessly shuffle around a murky cell, their void gazes searching for an ambiguous cue. Homogeneous in tired costume and ashen faces, the destitute prisoners amble in silent futility – resigned to the dim prospects of their ordained condition.

Video production still from Extracurricular Projective Reconstruction #35, 2010. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery and Kelley Studio.

The analogous Kandor 12 shares an equally inauspicious aesthetic; the cloudy brown bottle houses a municipality more reminiscent of chess pieces than modern skyscrapers – as if underlining the inmates’ loss of an unassailable game. The sparse backdrop of the gnomes’ cellar intimates a societal tradition of abhorrent secrecy and muted abuse of the weak, a ritualistic convention of marginalizing the vulnerable in order to preserve the greater hierarchy. As if acting as the underbelly to the rapacious actuality in EAPR #34, the vignette captured in EAPR #35 exposes the ensuing trauma that occurs in the wings as we strive to fulfill our socially performative roles – most of which remain immutably out of reach.

Kandor 12 A (green screen), 2010. Tinted Urethane resin, steel, blown glass with water-based resin coating wood, enamel paint, silicone rubber, acrylic paint, lighting fixture and Lenticular 12. 126 x 202 x 276 inches overall (320 x 513.1 x 701 cm). Photo by Fredrik Nilsen. Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery.

In fact, Kelley’s inclusion of the sets from the EAPR #34 and EAPR #35 videos in this exhibition make us feel but a mere player in one hell of a bewildering production. In tandem with his Kandors, the sets feel like an abstract extension of a transient ecology, a faux mise en scène demonstration of how we enact our own mortality. Do we unconsciously fall victim to institutional constructs in our quest for repute and satisfaction, acting a character merely to clinch our chances of eminence? Or do we find ourselves waiting in the wings for a cue – a protagonist – that may never come?

Kandor 10 / Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction #34 and Kandor 12 / Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction #35, installation view. Photo by Fredrik Nilsen. Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery.