Recovering Site and Mind: Richard Serra’s Sequence Arrives at Stanford

Over the course of its three-day installation in July 2011, Richard Serra’s “Sequence,” on loan from the Fisher Art Foundation, both reveals itself and conceals the expansive space it inhabits. Photos: Saul Rosenfield, © 2011, with permission of Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University.

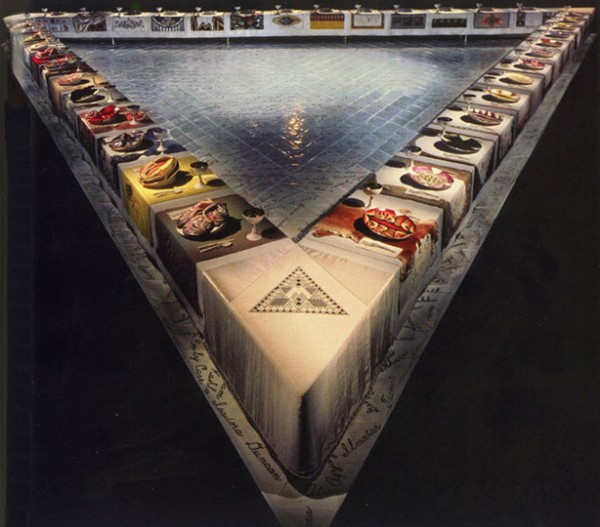

The Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University is engaged in a dangerous experiment, and it is not the levitation of a twenty-ton piece of Richard Serra’s steel sculpture, Sequence, 2006, thirty feet into the air. Nor is it the gyration of a 200-foot tall crane lifting the first of twelve panels—each almost thirteen-feet high and between thirty- and forty-feet long—from a flatbed trailer onto a concrete slab three-quarters the size of a baseball diamond. The ironworkers from the Hauppauge, New York, rigging company, Budco Enterprises, have handled all of Serra’s North American installations for the past 20 years. The dangerous experiment is, instead, the transplantation of the sixty-five by forty-foot labyrinthine sculpture into a site that the artist did not specify when he first created the piece.

Two 20-ton plates from Richard Serra’s Sequence, on loan from the Fisher Art Foundation, swing into place. Video: Rob Marks, © 2011, with permission of Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University.

Serra is famous for his site-specific sculptures. Of Tilted Arc, 1981, the 200-foot long grandparent to arced works like Sequence, Serra proclaimed, during a U.S. General Services Administration hearing to determine the disposition of the piece, “To remove the work is to destroy the work.” Commissioned and approved by the Carter administration, and constructed in lower Manhattan’s Federal Plaza, Tilted Arc was eventually decommissioned, forsworn, and bundled into storage by the Reagan administration. We can never know whether the Tilted Arc controversy—the first salvo of the 1980s culture wars—would have subsided had the surrounding political context not pre-empted the community’s process of coming to know the sculpture. Many of Serra’s public works, however, are now valued by the communities that first rejected them.

Other Serra pieces, including Clara-Clara, 1983, and Torqued Spiral (Closed Open Closed Open Closed), 2003, have, with Serra’s participation, found second homes. Sequence, however, may evolve into the most itinerant of Serra’s behemoths. Conceived for a gallery at the New York Museum of Modern Art and installed there in 2007 for Serrra’s 40-year retrospective, the sculpture traveled to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2008. This year, Sequence, now owned by the Fisher Art Foundation, traveled from LACMA to the Cantor Arts Center, where it is currently on loan from the foundation and where it will reside until in 2016. Then it will move, perhaps finally, 35 miles northwest to a new wing of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Left: Trailer as it prepares to move a plate from storage lot to installation site. Riggers remove the chains holding a plate to its trailer. Photos: Saul Rosenfield, © 2011, with permission of Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University.

Can Sequence, removed from its place of origin, sustain its prodigious capacity to shape space and lead us to the conscious and embodied experience of what we often take for granted? Will it still unmoor space and time from the feet and inches, seconds and minutes that define them in everyday life and provoke the reorientation of thinking and the individual psychological experience that Serra seeks for participants who engage the sculpture? In 2007, Serra told PBS’s Charlie Rose, “I think these pieces really need the definition of architecture,” referring to Sequence and its two gallery siblings. “They need a flat floor. They need a certain contained volume. I think these pieces might be able to be in a courtyard, but if you put these pieces outside, say in a big field, they’re going to get lost.”

Left: Master Rigger Joe Vilardi (center, in black shirt), and riggers John Barbieri, Joe Berlese, and Bill Maroney, survey the concrete slab. Right: Master Rigger Joe Vilardi (right) and rigger John Barbieri (left) plot reference points that will guide the installation of Richard Serra’s “Sequence” (on loan from the Fisher Art Foundation). Photo: Saul Rosenfield, © 2011, with permission of Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University.

The gallery at New York MoMA, an awkward H-shaped space with a low ceiling, seemed barely able to contain the three pieces. For some, this was the exhibit’s flaw: the sculptures had no room to breathe. We are used to viewing sculpture from the outside, framed by an expanse of space. For Serra, who seeks always to confound the viewer’s desire to see the entire sculpture at once, the cramped MoMA quarters may, in fact, have been preferable. Indeed, the frustration some visitors felt may have stemmed from the sculptures’ ability to stymie the creation of a purely visual experience separate from the body’s active engagement with them. In New York, Serra had produced new space in a place where visual inspection suggested there was little to spare. Within each sculpture’s orbit, the participant’s perception of space expands and contracts, independent of the gallery’s concrete dimensions. In this context, Sequence seemed akin to a magician’s hat from which emerges far more matter than could be contained by the dimensions of the magician’s head.

How then can such a piece successfully reconform itself—and the experiences of its participants—to an exterior space 3,000 miles away? How can the activity of getting lost in what Serra describes as “a seemingly endless path between two leaning walls” about which “you cannot recollect or reconstruct a definite memory” be preserved in a courtyard where landmarks—a roof, a terrace, a tree, even a hanging cloud—continually orient the participant?

Left photos: Lost inside Richard Serra’s Sequence (on loan from the Fisher Art Foundation). Right: Parapets of the museum’s old wing peek above the sculpture. Photo: Saul Rosenfield, © 2011, with permission of Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University.

On Monday, July 18, the bare concrete pad seems to provide some reassurance. Two- to three-feet thick and doubly reinforced with rebar, according to Cantor Operations Manager, Steve Green, the pad should satisfy Serra’s desire for a flat floor. More than this, however, nestling the bulk of the sculpture into the cul-de-sac formed by the Cantor’s original building, its octagonal extension, and its new wing, seems to realize the “definition of architecture” Serra had specified for Sequence and its siblings. Further, Museum Director Tom Seligman said that the Cantor Center had been in close contact with Serra, and the artist approved of the site.