Best of PULSE LA

There is another art fair in Los Angeles.

Art fairs are synonymous with crowded, cavernous booths, prepackaged artwork, and most of all: money. But, this new art fair in Los Angeles does what very few art fairs have managed in the past; PULSE has combined a strong, experimental group of galleries and project spaces with actual money making. Combining gallery booths with project spaces for non-profit institutions and artists, PULSE delivers sculpture, installation, photography, and painting from some of the world’s most interesting contemporary artists. Having a strong presence in New York and Miami, PULSE opened its doors in Los Angeles to an all new crowd on Friday September 30th, and will continue through 5pm this evening. DailyServing sent three writers to PULSE LA to bring you the most interesting and noteworthy projects.

Allyson Strafella, Von Lintel Gallery, Booth B-9

Allyson Strafella, “Crenelation,” 2006. Typed dashes on green transfer paper. 6” by 10”.

By its very nature, an art fair overstimulates. This might be the reason my eye landed on Allyson Strafella’s work, a series of simple and colorful geometric forms, à la Ellsworth Kelly: two deep red rectangles, one black, and one more I can’t quite recall—possibly something voluptuous and green floating in a field of white. They looked out of place, overly simple and stubbornly modern. Yet…they wobble. They even seem a little furry. Strafella works on a customized typewriter, with a special set of keys and a much wider bed than what any of the secretaries on Mad Men would use. She chooses flimsy papers, including colored carbon papers, which she then inserts into her machine and completely distresses through repeated mechanical contact. In some places that Strafella hits over and over with the typewriter keys, the paper becomes lace-like, or begins to fall apart. The results hover between sculpture and drawing, bringing new texture to an old form.

Allyson Strafella is represented by New York’s Von Lintel Gallery and can be seen for one more day in booth B-9.

Written by Danielle Sommer.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Kenji Sugiyama, Standing Pine Gallery, Booth I-7

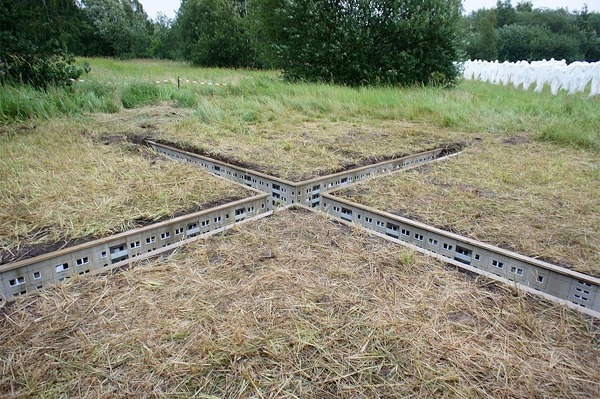

Image Caption: L: Kenji Sugiyama, detail from Institute of Intimate Museums: Mazes, 1998, mixed media installation; Right: Kenji Sugiyama, installation view of Institute of Intimate Museums, 2000, mixed media installation. Courtesy Standing Pine - cube.

Japanese gallery Standing Pine’s whole booth is devoted to obsessively detailed miniature “museums” by artist Kenji Sugiyama. They’re small cardboard boxes or round viewfinders the size wiffle balls that you can look through to see a whole exhibition installed to scale. At Pulse, a long line of flimsy pasta boxes sit on a white shelf, and when you crouch to look through one end, you’ll see a corridor assembled in a pristine, calculated manner, with faux wooden floors, framed images lining the walls, and benches spaced along the center. Sugiyama calls this series of work, which he began making in 1999, Institute of Intimate Museums and each museum exhibits tiny installations of his own work. This makes the project slightly solipsistic, but teeny-tiny solipsism, it turns out, can be delightfully idiosyncratic.

Written by Catherine Wagley.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Hong Seon Jang, David B. Smith Gallery, Booth A-7

Hong Seon Jang, Green Forest, Tape on chalkboard, 24 x 36 in., 2011 (Detail)

I always love to see what galleries have tucked away in their closets at art fairs – interesting work is often times hidden behind closed doors, drawn curtains or around a corner. I was pleased to peak down the closet hallway of Booth A-7, Denver’s David B. Smith Gallery, where a small work by New York based artist Hong Seon Jang is hung. By meticulously applying layers of tape on a chalkboard, the artist creates an idyllic scene of a deer in a forest, capturing the subtlety of shading, pattern and depth using only this simple material. His use of tape – a material employed for its temporary nature – adds a sense of physical vulnerability to the work, challenging what may initially be seen as simply a beautiful image.

Written by Allie Haeusslein.