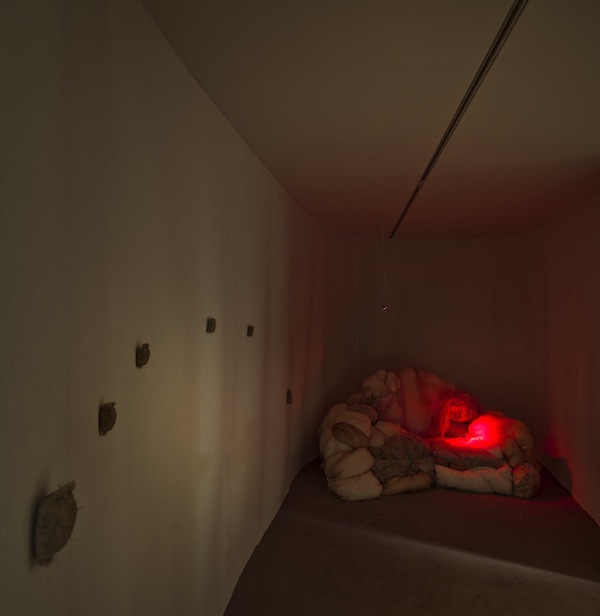

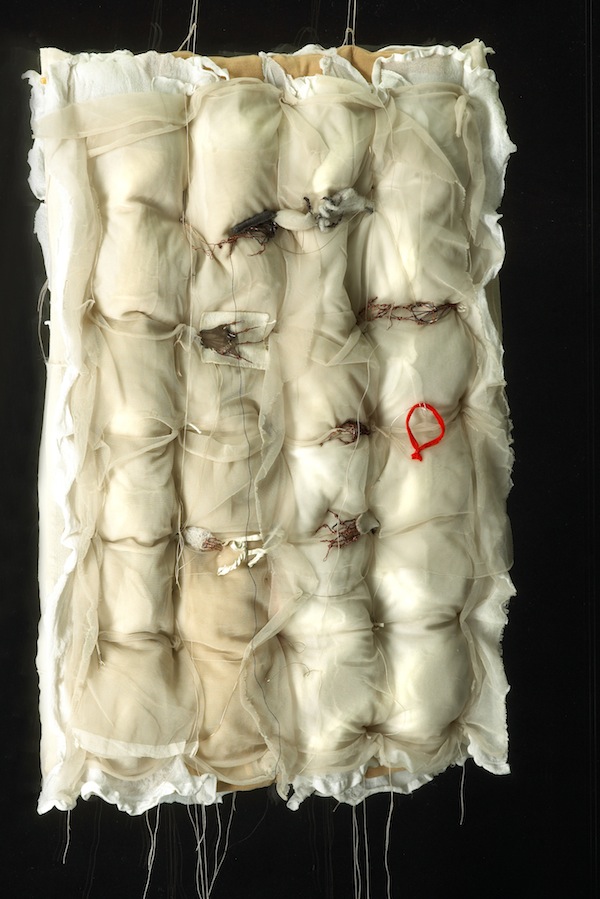

Christine Ay Tjoe, The Famous One from Lucas, 2011, Installation view. Photo: Edward Hendricks.

A biblical parable tells of a wayward son who leaves home for a distant land after demanding his inheritance from his father. Squandering his riches quickly, he repentantly returns to his father’s house hoping to be hired as one of his father’s servants but find instead, his father’s unexpected kindness and forgiveness. Christine Ay Tjoe’s current site-specific show The Famous One from Lucas # I at the Hermès Art Space references this well-known narrative of prodigality, articulating the interdependency of loss/gain and despair/hope through soft-fabric sculptures constructed out of goose-feathers, tulle fabric, stockings and industrial felt.

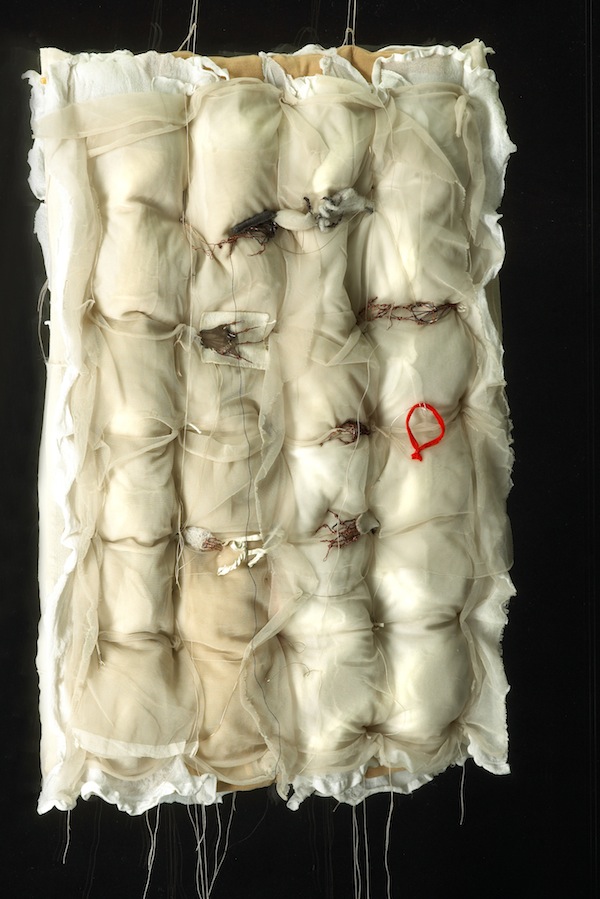

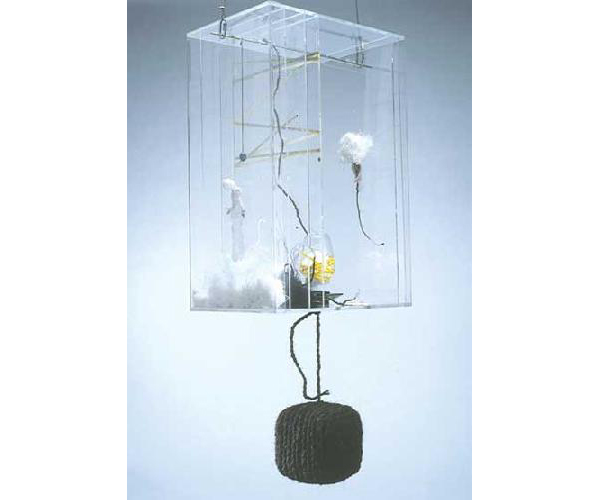

Christine Ay Tjoe, 24 of Us 65, 2006, Mixed Media and Glass Box, 65.5 x 50 x 6 cm.

Attempting to sublimate the profound personal workings of hope and despair into rituals of healing and rebirth has been a recurrent theme in Tjoe’s artistic practices. Unlike what we’ve come to expect from many contemporary Asian artists who respond to political or social change, Tjoe’s sensibility veered off this course early on. In 2003, her installation Santa/Satan at the CP Open Biennale was an acerbic critique of government authorities encumbered by bureaucracy and its trappings. But at some stage, her artistic gaze had turned inward, probing out suitable platforms on which questions of the transcendental could be raised. “I’m interested in the relationships between theology and humanity, which give rise to perceptions on the range of human emotions, motivations and experience,” she writes in an email interview, when asked if there were indeed, fundamental questions about art and religion that she had always sought to answer. “It relates to universal human experiences and emotions such as joy and grief and human expressions in extreme situations – this is something I’ve been curious about and continually investigate in my works.”

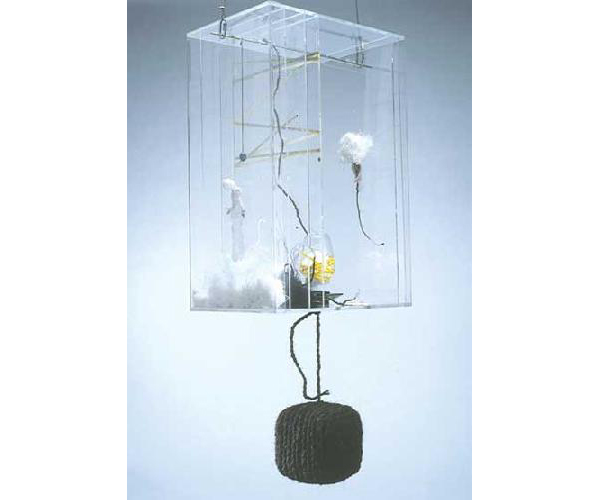

Christine Ay Tjoe, Santa/Satan, 2003, Installation, mixed media, 80 x 52 x 37 cm.

Steered by spiritualistic meditations and cosmological perspectives, her works are unsurprisingly attuned to the allegorical and the symbolic, utilising ephemeral spaces and fragmentary images that comment on the irreducible essence of flawed human nature. Lama Sabakhtani Club (2010) compares the tragic scale of loneliness and anguish to Christ’s ordeal on the cross in a series of installations assembled by strings, nails and fabrics. In Interiority of Hope (2008), Tjoe’s imagines the psychological state of the criminal Barabbas – the man Pilate released instead of Christ at the demand of the people – as one caught between the joy of his release and the unrelenting guilt of the crimes that he committed. In both shows, the forms of her work often appear as impressionistic renderings of complex lines or as misshapened entities whose purpose remain ambivalent. They share an allusive and elusive quality that often suggests that materials from without exist only to reveal the malleability and flux found within, elucidating an artistic vision that treads dangerously close to rehashing Renaissance humanist patterns of self-knowledge and its limitations.

Christine Ay Tjoe, Barabas Lights no. 07, 2008, acrylic on canvas, 170 x 135 cm.

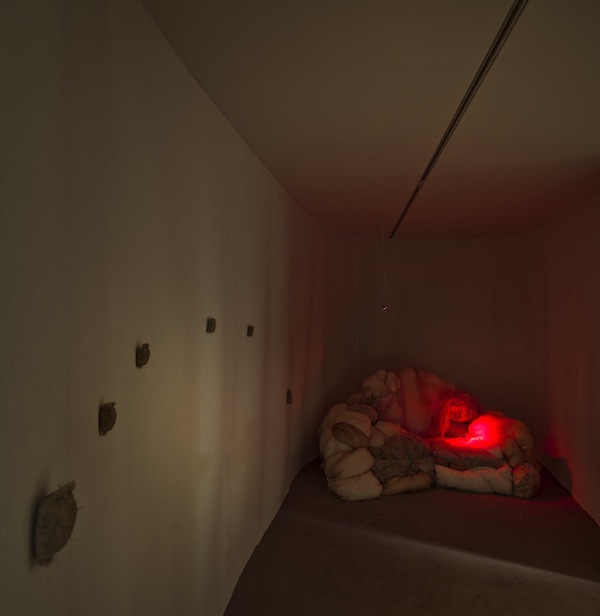

The Famous One from Lucas # I continues Tjoe’s exploration of materiality as metaphor for the esoteric nature of the human condition. Textiles are primarily transformed into both familiar and non-familiar objects – a worn-out sofa and a teddy bear being the more recognisable ones –, their surface textures and form adding, according to Tjoe, an interesting dimension of sensation especially for the object art she creates. But like wanderers in a labyrinthine environment, it is hard to tell where The Famous One from Lucas # I starts and ends, despite Tjoe’s assertion we are walking through memory markers (displayed as physically undefined objects along cocooned walls) that express the journey of one’s life. We know the show’s conceptual starting points: the sheer greyness of the human psyche dictates that hope and despair are faces of the same coin, defined by their relation to one another. Yet the lack of linearity in its atmospheric spaces, soft curved walls and winding pathways seems to scope out a more cosmic intersection of nature and nurture; it introduces into the visitor experience a hint of the tenuous boundaries separating the cerebral and the emotional, the past and the present, the spiritual and the carnal.

Christine Ay Tjoe, The Famous One from Lucas, 2011. Photo: Edward Hendricks.

The physicality of the work reflects its metaphorical framing; we inexplicably find ourselves wandering in its pathways numerous times, beginning where we end, ending so that we could start once more. In this visual text, we can participate in the shameful indulgence and repeated transgressions of prodigality while simultaneously walking the passage of redemption and liberation.

***

The Famous One from Lucas #I was on show at the Hermès Art Space until November 27; this article could not have been completed without the contribution of Christine Ay Tjoe herself in an email interview and the support of Hermès Art Space and the Singapore Tyler Print Institute.