Francesca Woodman at SFMOMA

On view at SFMOMA and traveling to the Guggenheim in 2012, Francesca Woodman is a testament to the faithfulness of an artistic inquiry. In photo after photo Woodman experimented with formal elements, tested endless configurations, and explored feminine identity. Woodman’s self-discipline is evident in the multiple galleries hung with her photographs. Considering her age—she was in her late teens and early twenties when the work was made—her tough-minded dedication is rather surprising: to produce the 174 photographs now on view, she had to have been in front of or behind the camera, or in the darkroom, to the exclusion of much else.

Woodman most often acted as her own model, and the small black-and-white compositions, usually nudes, are visually straightforward but conceptually complex. What complicates the work is the knowledge that Woodman is not just the vulnerable nude, but also the architect of that condition. In many photos Woodman’s gaze is directed at the viewer; and yet knowing she was also the photographer mediates that directness, because ultimately what her model-self was looking at was her photographer-self, backwards through the lens of the camera, posing for her own view. In this way, she was able to explore her femininity as a construct of at least partially her own making, bringing a feminist awareness to her investigations.

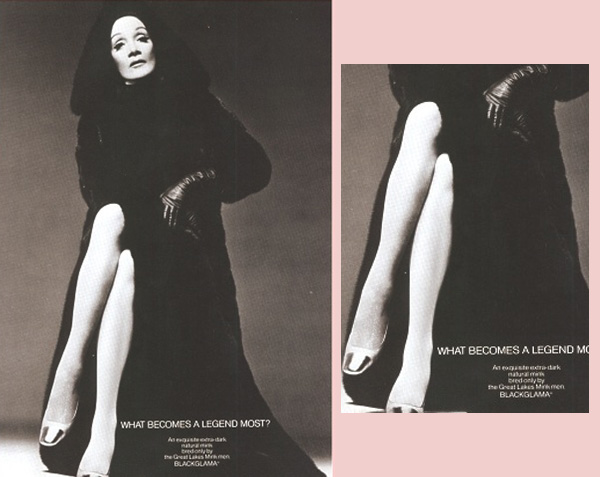

Francesca Woodman, Polka Dots, Providence, Rhode Island, 1976. Gelatin silver print, 5 1/4 in. x 5 1/4 in. Courtesy George and Betty Woodman

Take, for example, Polka Dots (1976). Wearing a spotted dress, Woodman crouches against a decaying, dilapidated wall. Over her head there is a fist-sized hole punched through the plaster and lath. Similarly, her dress is unzipped at the side, revealing part of her torso and the curve of her left breast. Splayed fingers hide her mouth, heightening the vulnerability of her posture and semi-nakedness, and her messy hair corresponds to the ruined nature of the room. Her awkward, submissive pose and undone dress belong to a madwoman—but her eyes are not crazy, they are guiltily sexual. They dare the viewer to compare the hole in her garment to the hole in the wall and to see how they might be similar. And yet the title is neutral, focusing coyly on the pattern of the dress and the concurrent black spots on the wall, redirecting the viewer to the composition as a whole and reflecting the conceptual slyness of the work. Contradictions and ambiguity create depth as Woodman refuses to provide an easy summary of femininity or desire.