London

Gillian Wearing Wearing a Mask of Gillian Wearing

British-born photo, video and performance-based artist Gillian Wearing is best known for bringing home the 1997 Turner prize and her series of direct street portraits, Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else wants you to say (1992-3). At London’s Whitechapel Gallery, the artist presents a fascinating collection of honest, if not creepy, portraits in an exploration of the public and the private, the concept of everyday performances as well as the psychological complexities of wearing masks. Woven throughout layers of artificiality and deception a thread of reality continually shimmers through. Wearing often elicits the participation of real people, with real confessions, real trauma and real fantasies. Although they hide behind anonymous masks and a handful sound rehearsed, these video performances were made for the sake of revealing personal truths.

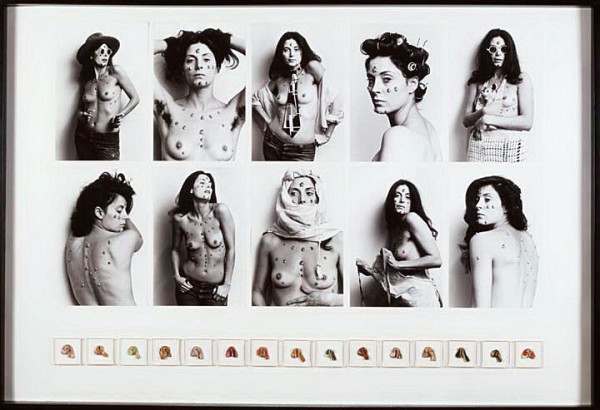

Wearing has been very attracted to the lives of others and seems interested in breaking down the common, frosty perception of strangers in the public realm. Prelude (2000) shows video footage of a vagabond who Wearing had filmed just before her death. The audio narrative, touchingly told by the deceased’s twin sister, tells of her struggles with the bereavement while images of her sister smiling and flirting with the camera play on. Much of the artist’s work contravenes against everyday apathy with the telling of such personal stories. The artist put out a local ad in Confess All On Video. Don’t Worry, You Will Be In Disguise. Intrigued? Call Gillian…(1994) and a series of videos is its result. Admittedly, some confessions are less inviting and a bit uninspiring. The work’s purpose ends at the relief or amusement of the confessor, and they were clearly chosen only for their racy content. Yet, others draw you in. One of the most poignant confessions comes from a man in a scraggly black wig and heavy red lipstick who reveals heavy-heartedly his enjoyment in wearing women’s clothing and the pain it causes his loved ones.

Gillian Wearing, Dancing in Peckham, 1994, Colour video with sound, 25 min. Courtesy of the Artist; Maureen Paley, London.

How are we expected to act in public? Everyday public interaction is certainly a collection of learned behaviors based on expectation. Wearing’s Dancing in Peckham (1994), pokes fun at such conformist social expectations. In the video-performance Wearing famously dances in public (vigorously) to a beat that exists solely in her head. The iconic image may be familiar, but one might be surprised to learn that the work was not as much a social experiment, but rather, a re-enactment, inspired by an actual woman whom the artist witnessed in a similar unstaged performance.

Probably the most haunting and beautiful series is the array of massive family portraits lining the walls of the upper gallery. They seem both sentimental and idealistic on the surface, yet are completely unsettling. We see an uncle, a father, a daughter, a mother – the portraits of anyone’s family, scrounged like forgotten ghosts from a dusty, abandoned shoe box. Generational features appear, revealing that these are the faces of the artist’s family…right? The doll-like faces bear unnaturally smooth swathes of skin, and imperfectly aligned eyeholes a divulge grotesque, silicon artificiality. Beneath the mask, a repeated flicker of life peaks through: the gold brown eyes of Gillian Wearing. The Album series are really self-portraits, the artist exploring her own identity by familial impersonation with the aid of realistic masks.

Gillian Wearing, Self Portrait as My Mother Jean Gregory, 2003, framed black and white print. Courtesy the artist.

Wearing’s personal display is also universal, effectively evoking thoughts of one’s own aesthetic ancestry. In browsing through ancient family photographs, who of us has not had the uncanny shock of seeing one’s own face staring back? Feeling both violated and enchanted, we realize that the time and place captured in film belongs to strange doppelganger we have never met. This person is connected to you, looks like you, but is not you.