Chicago

Just Say Yes

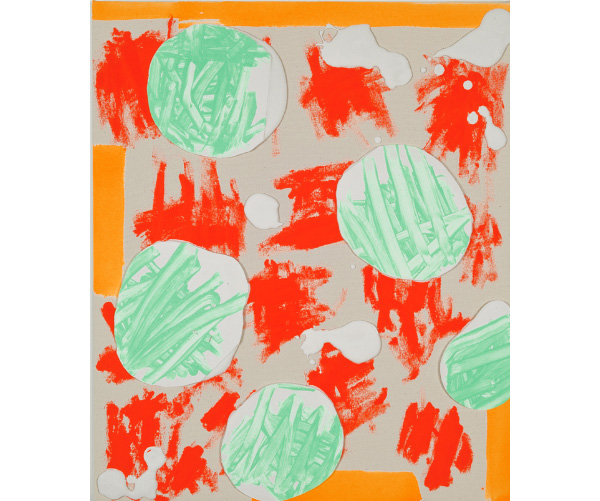

Zachary Buchner, Untitled (JYS 08), 2012. Plaster, acrylic, and tempera on canvas. Courtesy of Andrew Rafacz

Looking at Zachary Buchner’s one-man show of mixed media plaster paintings at Andrew Rafacz Gallery entitled, Just Say Yes, I couldn’t help but think of Julian Schnabel’s sculptural plate paintings from the 80’s. In both cases, the dense treatment of the surface straddles the line between sculpture and image while exploring painting as an idiomatic language. Unlike Schnabel, Buchner doesn’t go in for representation or introduce any narrative or iconographic elements that would distract from the purity of this investigation. He’s not building a surface over which to paint a picture. The way Buchner layers paint and plaster creates an integrated whole that preserves the basic characteristics of each. The materials are always distinguishable from one another. They exist in the same plane – over lapping, covering – though there is never a breach of material autonomy.

Buchner’s work is very much in the tradition of painting about painting. That’s not meant to be a de facto criticism, but it does suggest a strategy for approaching the work that requires a certain openness on the part of the audience.

Buchner’s investigation is distilled to a few key concepts; specifically, the boundaries of integration through material engagement, surface density, the interplay between “neutral” material colors like the white of the plaster or beige of raw canvas with the vivacity of saturated hues – all within the confines of a specific rectangular format. The mark making is generally restrained and absent of much expressiveness or lyricism, and shapes curb toward organic round-ish blobs. Color becomes a real source of energy within the work. In Untitled (JYS 08) (all works are from 2012) a splotchy layer of white plaster rests over tones of warm green, bright yellow, and silver. Shards of blue painted plaster imbedded in and framed by the white pops out in front of the acidic background like icy ruptures.

Untitled (JSY 12) intensifies the use of layered plaster while minimizing the use of color to a few bold strokes. Several irregular plates of white plaster are stacked in a thick ring over grayish purple undertones. In this piece, dashes of forest green contrast dissonantly with bright red-orange rectangles. One of the most dimensional works in the show; the layers of plaster create more of a relief sculpture than a traditional two-dimensional image.

Similarities from piece to piece begin to reveal a systematic working method of applying a two or three color underpainting, followed by a layer of plaster topped with dashes of a contrasting color. Individual pieces separate themselves from the group based on the success of how this formula is applied. Untitled (JSY 09) is one of the most finely integrated works in the show. Paint, color, shape, and the mixing of materials all come together with the poetic power of late Cy Twombly. Like Twombly, Schnabel, and countless other artists, Buchner’s work provides one more voice to the ongoing conversation about the sensory pleasures of painting.

Just Say Yes will be on view at Andrew Rafacz in Chicago through May 5, 2012.