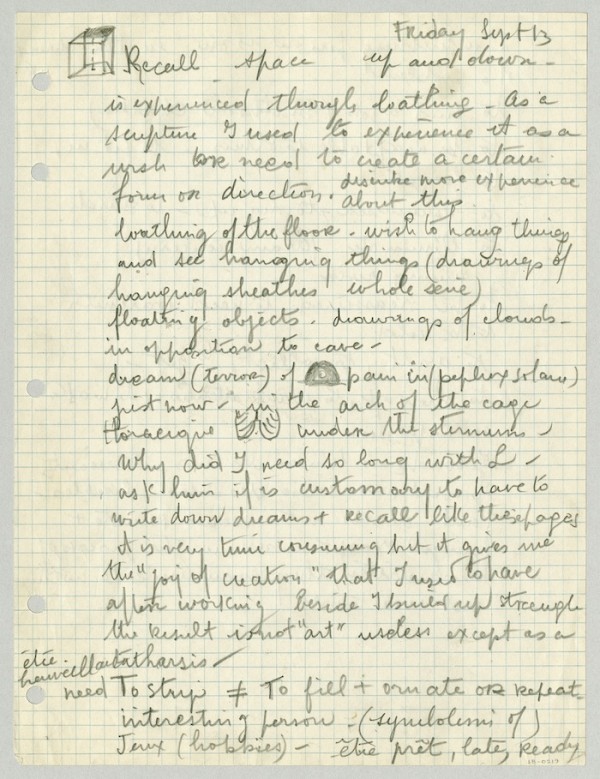

Installation view of Back to the Things Themselves (Lesley Punton & Judy Spark). Image courtesy of Lesley Punton.

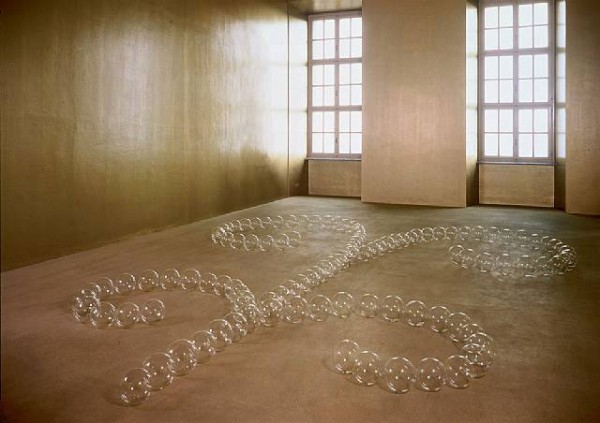

Back to the Things Themselves, on show at The Briggait, presents artworks by Lesley Punton (LP) and Judy Spark (JS) who both explore possibilities and limits of translating one’s lived experience of the environment, and the potential for connections between a subjective experience with universal ways of knowing the world.

Magdalen Chua (MC) had a conversation with Punton and Spark, as a second part of a feature on exhibitions presented during the Glasgow International Festival of Visual Art that place emphasis on the process of collaboration and the subjective experience within artistic practice.

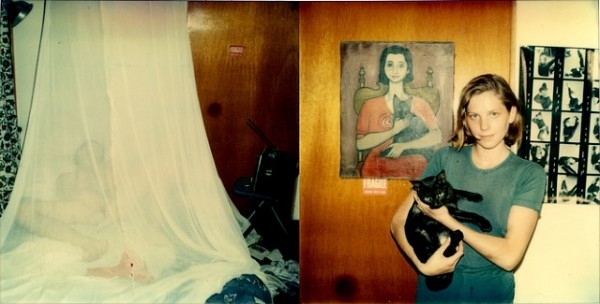

Judy Spark, Like punctuation (symphoricarphos), Graphite on paper, 2012, (with Lesley Punton White out receding – Carn Dearg to right). Image copyright and courtesy of artist.

MC: Shall we start off by talking about your individual practices?

LP: My work has always been concerned with landscape issues. In recent years, through the process of walking, it has become more explicit in relation to my lived experience of places that are usually wild and rarely urban. In the exhibition, I have tried to create a diverse conversation between different pieces of work, exploring the limits of experience; and polarities – of night and day, light and dark, and time and duration.

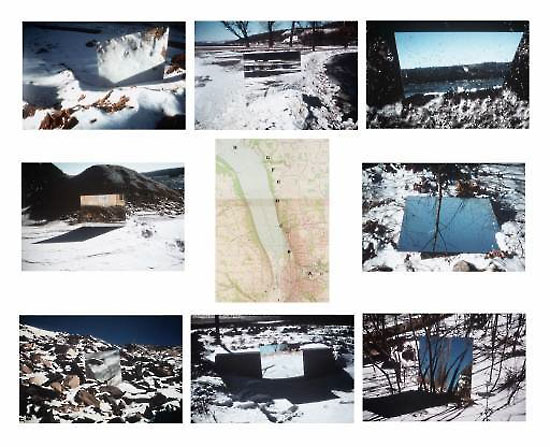

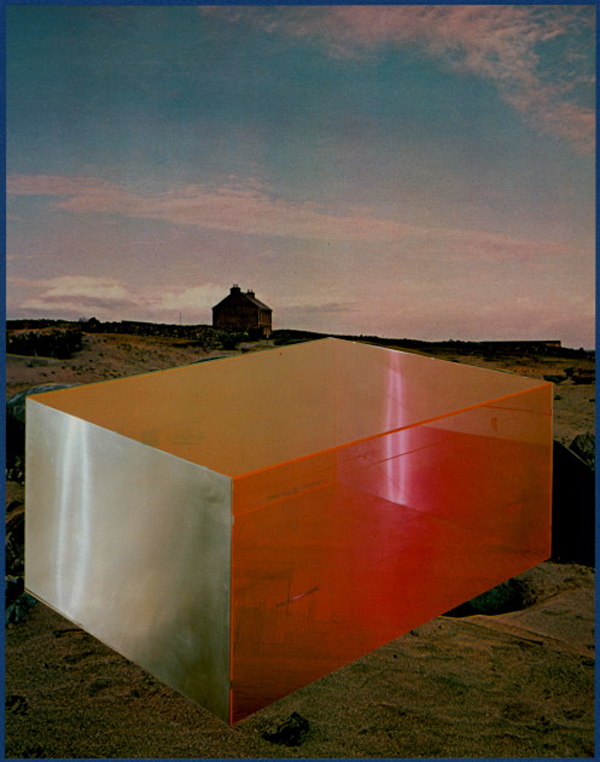

Lesley Punton, Schiehallion, silver gelatin 5 x 4 contact print made after placing a pinhole camera in the summit cairn, pointing South, whilst bivying on the summit of Schiehallion to record the duration of the hours of darkness of midsummer night ’09, 2009-12, with Jim Hamlyn. Image courtesy of artist.

In the past, a lot of the lived experience of my work resulted in long and complicated processes of making. There are works that are directly durational in their actual making, such as Flurry, which marks time. A participatory work is Schiehallion where Jim Hamlyn and I made a pinhole photograph that recorded the duration of midsummer’s night that year at the summit of the mountain. These have a very direct relationship to experiences whilst actually in land. Recent works respond more to reflection and recollections of those experiences. Some have literary connections. Gravesend is the place where the narration of ‘Heart of Darkness’ starts, with Marlowe sitting and recounting the tale of his experience with Kurtz up the Congo.

Lesley Punton, Gravesend, graphite on paper, 2010. Image courtesy of artist.

MC: Could you talk about the Duration pieces? They make me think of a journey, where the days refer to the duration, or the process of making the work.

LP: The duration refers to polar night and polar day and the idea of time as something that is not quite fixed. I’ve always been interested in aspects of time – deep time and geological time – probably from the experience of spending a lot of time in hills.

Lesley Punton, Duration 2, oil & gesso on board, 2010-12 (photo credit L Punton). Image courtesy of artist.

MC: When did you start looking at the idea of the lived experience and venturing into remote places?

LP: I’ve always believed that you would make something that has some relationship to how you connect with the world. The intensity of the experience of walking and climbing mountains was something important and I became a bit obsessed with it. It felt unnatural not to do something with it.

Judy Spark, The things themselves, Two FM radios / transmitters with digital soundtracks, 2012. Image copyright and courtesy of artist.

JS: My route to making work about lived experience was through a concern with mechanisms like environmentalism that are established to get people to recognize the value of their surroundings. Environmentalism of any kind – whether related to ecology, renewable energies etc., – depends upon the scientific mechanisms that have created the problems that we’re facing in the first place. In the last 5 or 6 years, I’ve begun trying to find ways to think about how people engage with their surroundings. Conversely to Lesley, my landscapes might be right under my feet. It tends to be urban because that’s the environment I’m treading on all the time, and that’s how things come to consciousness.

MC: Could you explain the basis of your philosophical approach. It seems to be about being within a certain environment, perceiving what is around you, and letting these surface.

Judy Spark, Instructions for creating a gap, Printed text, 2011 – 12. Image copyright and courtesy of artist.

JS: A big influence was a Master’s in Environmental Philosophy in 2006 which broadened my thinking. There doesn’t seem to be much between the poles of not really caring about the place that you inhabit, and having a code of rules that are scientifically directed on how you should behave. We’re not used to working out anything in-between that is more personal. Trying to find a subjective response to things might actually turn out to have wider relevance than “just my own personal subjective response”. I became interested in the phenomenology movement and the idea of trying to describe actions or processes in a way that allows people to find something more direct and new. I think there are parallels with more indigenous or Buddhist experiences of the world which I can’t be a part of. I’d love to be, but I would only be putting my own Western perception onto them.

Judy Spark, Listening in the gap, Bound, printed text. Image copyright and courtesy of artist.

MC: I had a conversation with Sarah Forrest and Virginia Hutchison, and we spoke about the subjective experience and values. When there is an objective framework such as environmentalism, it is easy to subscribe to it because it is clear what kind of values there are. When we move to the subjective, it opens the question of whether there are still values within this realm.

LP: As much as I might prioritise a lived experience and the subjective, my relationship with the audience is more objective. I’m always looking for a distancing mechanism. The act of translation in the artwork gives the potential for objectivity or a poetics of space, which the viewer could enter into with their own subjective experience. If I thought for one second that what I was making was self-indulgent work, I would run for the hills, literally. At the same time I have no interest in creating distanced work. While my work might be incredibly minimal, I hope that there is a poetic layer that subverts that sparseness.

JS: The notion of value is an interesting one because of the distancing that you talk about. I know that I have a bit of a drum to bang in some way, but I can’t use my artwork for that and I wouldn’t want to try. It really is about putting something out there and if it allows viewers to think about their own response to things, then great.

Lesley Punton, Flurry, silverpoint & gesso on paper, 2008. Image courtesy of artist.

MC: How did you meet and what led you to decide to collaborate on this exhibition.

LP: A mutual friend was planning on hillwalking in 2004 and we started regular weekend walks.

JS: We did talk about the possibility of showing work together for years and have had many conversations. When we secured the show, I became very busy. Lesley has a young son and we both work. The collaborative aspect probably starts now in the debriefing of what we’ve done.

LP: As we have individual practices, it was probably important that we had our time to make our own work.

JS: Now that we have put our work in proximity like this, maybe this is the beginning of the next stage

LP: Walking is a very interesting way to collaborate and to build friendships. There are extended periods of silence and these are different from the conversations you have when you meet somebody in the pub. You actively experience something together. I have made some works where I have collaborated with Jim Hamlyn, my partner. The notion of collaboration is still quite new for me in the actual making of artworks together. Up until very recently I’ve not formally collaborated.

Judy Spark, Orrery (gallium aparine), Graphite on paper, 2012. Image copyright and courtesy of artist.

JS: I’m usually a very isolated practitioner. I teach in an art school and that’s maybe where I get a lot of my energy. Collaboration is something I haven’t made a decision not to do. It seems to be closely connected to that thing of value. Maybe if I meet another artist whose work or practice, or something they say to me about my work or practice, chimes in a way. Maybe it’s to do with being a friend first.

LP: I think collaborations grow organically. I don’t think you can just put two people together and say collaborate, do it now. It doesn’t work that way.

MC: Perhaps you need a lot of trust. It starts off from conversations and knowing that those conversations can take place even without the art.

LP: …and equality as well. If there’s an imbalance there, I don’t think you can collaborate, and that’s where your idea of trust comes in.