Help Desk

Help Desk: Putting It Out There

Help Desk is an arts-advice column that demystifies practices for artists, writers, curators, collectors, patrons, and the general public. Submit your questions anonymously here. All submissions become the property of Daily Serving. Help Desk is co-sponsored by KQED.org.

Like two other artists that wrote in [see Help Desk: Location, Location, Location], I also live in a part of the country that doesn’t have the strongest art market. I get to show locally a few times a year and the artistic community, made up of locals and university members, can be creatively stimulating, engaging and supportive. It’s a great place to make art, but a not-so-great place to sell art.

My question is, what value do you see in “alternative” exhibition spaces, both digital and physical (Saatchi Online, White Columns Artist Registry, and New American Paintings as a few examples), for being legitimate avenues that lead to show opportunities at galleries in metropolitan art centers? Can having a strong online presence be enough to catch the attention of curators and galleries that already have a line of hopefuls at their street address?

Acceptance to an artist registry or a curated publication holds the promise of getting your artwork in front of people who are interested in exhibiting, selling or buying it. But does it really work like that? Are there success stories? What are the pitfalls? I asked around to find some answers.

One artist I spoke with was initially very excited to have his work included in the White Columns Artist Registry. However, he told me that in the few years that have passed since his acceptance, the only result has been an increase in the amount of junk mail he receives. He does still take the time to update his page, but assumes at this point that nothing will come of it. Another artist whose work was accepted for a New American Paintings catalog a couple of years ago told me that it “did not pan out into anything.”

One of the first adopters of Saatchi Online said of the registry, “I don’t think it hurts – but I cannot say it has helped yet. I did receive a query…and they may have found me on Saatchi, but nothing has come of that yet. Otherwise it is such a mixed bag there – most of the artists are not that developed… [but] they do find serious curators for their Showdowns.” She added, “To be frank, nothing is as good as your own website – and this goes for Blogger, Tumblr and the million other ways you can expose your work.”

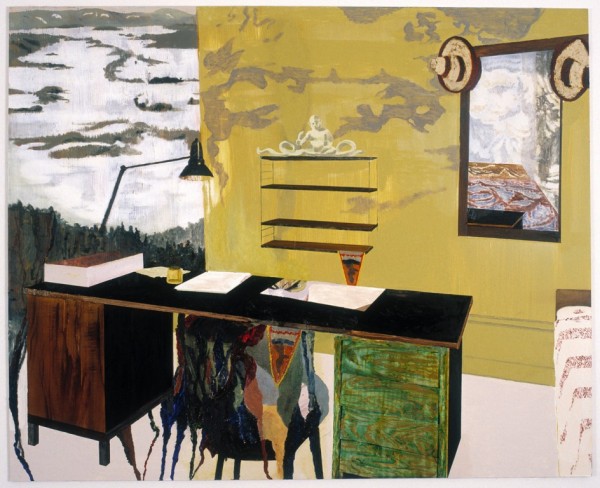

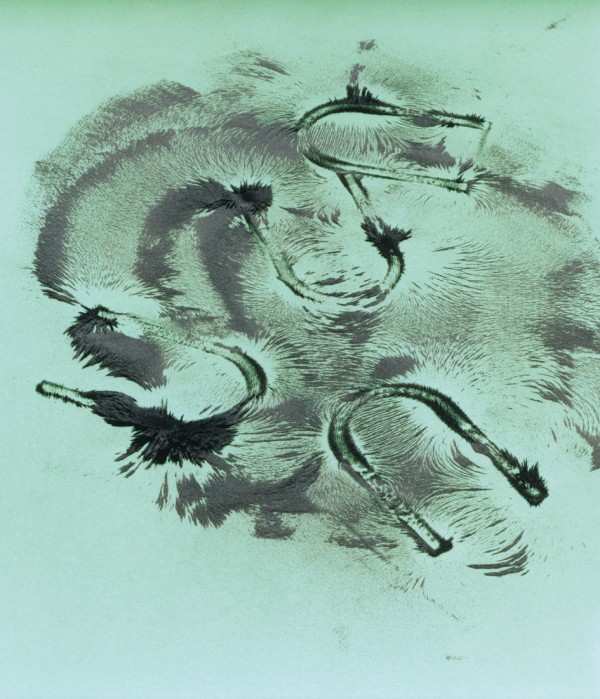

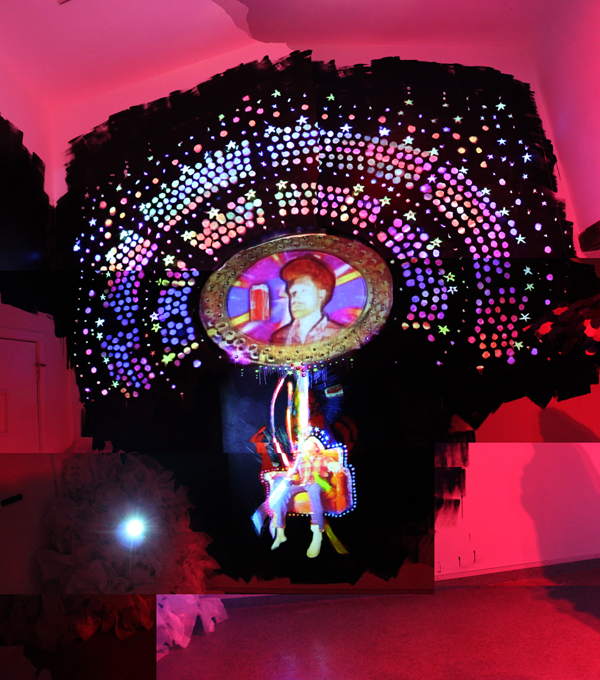

Granted, these are the accounts of only three random artists among thousands, so it’s hard to say if theirs is the experience of the majority or not. I’d like to believe that the registries are helpful–readers, please note that Saatchi Online was where I found the collages of Irina and Silviu Székely, featured in this column a few weeks ago–but the last part of your question acknowledges the necessity of actually being physically present, at least sometimes, in order to be on a gallerist’s or curator’s radar.

There are no certainties in this game we play. By all means, I think that providing one more place for gallerists and dealers to find your work could prove helpful to your objective of selling. But don’t let the energy you’re putting into an online presence take away from the time you spend connecting to people in real life. The glib phrase “it’s who you know” is not quite accurate—you could be on a first name basis with the pope and it won’t make your work any better—but it’s not entirely inaccurate either. If you do pursue and get your work into these registries, see if you can use that as a very deliberate stepping stone to a face-to-face meeting with a gallery you’ve had your eye on.

I’m an artist without an art school background. I’ve made art my whole life but only for me personally, until the last few years, when I began to devote much more of my time to it and to put it out in juried shows and other exhibitions. I’ve had some serious encouragement with a few large sales and two solo shows (one in a high quality art venue, one in a public space) in the four years since I changed course. I remain self-employed in my “day job” which is tangentially related to the art I make in that I carry themes over from one realm to the other. My question is about how to portray myself to galleries as I reach out to them. I want to be honest about my background but I am realistic enough to know that there are some prejudices against those who come later and roundabout to artmaking. I want to emphasize that I am extremely serious about it and hope to make a complete switch if at all possible.

I think you should portray yourself honestly: you have been making art your whole life and have recently produced some bodies of work that have been successful in the marketplace. In terms of gallerists and dealers, why would any other information be germane to the matter at hand? Do I need to know if my dentist has an undergraduate degree in modern dance, or do I want to know if she is experienced, licensed and insured? Capisce? No one (at least no one you’re going to care about) will give a damn about art school if your work is strong and interesting, you present yourself well and have a good statement.