Help Desk is an arts-advice column that demystifies practices for artists, writers, curators, collectors, patrons, and the general public. Submit your questions anonymously here. All submissions become the property of Daily Serving. Help Desk is co-sponsored by KQED.org.

.

As an independent curator also affiliated with the programming of a commercial space, I often find a strange tension during studio visits as to whom the visit is on behalf of. As clearly as I try to communicate that my interest is for personal projects, I frequently find myself reiterating in future correspondence that I am not in fact offering representation or an exhibition opportunity on behalf of the gallery. What is the best way to navigate this sort of conflict without being misleading to the numerous artists I have the pleasure of visiting? While it seems appropriate to communicate this before we even meet, I also feel conflicted as to how an immediate disclaimer reflects on my attitude/open-mindedness. Any advice as to timing and phrasing would be a tremendous help!

Your position is a tricky one, and I appreciate that you want to be on the level with the artists whose studios you visit. It sounds like the message you impart about your role isn’t always being taken seriously, and I wonder if some of the artists you are visiting have clogged ears or an overdeveloped sense of optimism. Perhaps despite all the evidence to the contrary they think that you are just testing them, humbly disguising your real intentions to offer them a solo show at your employer’s gallery if the visit goes well.

John Baldessari, Man with Blue Shape, 1991. Photograph, 77.5 x 122 cm

In any case, it’s going to behoove you to be confident and direct with your message. I know that artists can sometimes seem misguided, but since you say you feel conflicted about making disclaimers, I wonder if you are really being as forthright as possible? You can avoid confusion or hurt feelings by stating your intentions candidly. By making sure that you convey your specific and limited role when you make the initial contact for the visit (by email, that way it will be in writing), and again in person when you begin the studio visit, you can avoid a miscommunication. You don’t need to feel conflicted about this. Personally—and I suspect I am not alone in this opinion—I would rather work with a curator who speaks plainly about her position and interest.

In writing, you might try something like, “Though I do work for Gallery X, my interest in your work stems from my own curatorial practice, independent of my employment.” In person, you might want to start the conversation with, “Just so you know…” “Before we really get into it, I’d like to make it clear that…” or “Because of some confusion in the past, I want to clarify…” By reiterating your position in person, I hope you’ll drive the message home. If you think you might be uncomfortable saying something like this, rehearse it with a friend or in front of a mirror. When you deliver your lines, check to make sure that the artist is nodding or otherwise indicating comprehension before you move on. If an artist asks you about representation or other opportunities at your employer’s gallery, you can just say, “Unfortunately, I don’t have that kind of decision-making power.”

If you’ve outlined your position twice, in writing and again face-to-face, and yet need to reiterate your intentions to a particular artist it might be a warning sign that this person will be difficult to deal with in the future.

John Baldessari, Two Whales (with People), 2010. Screenprint on paper, 32.25 x 23.60 in, edition of 50

I am an emerging artist in the process of a minor transformation and I could use a little advice. For the past ten years I have made sculptures and installations that are mechanically and technologically very complex. Because of this I have always maintained a large studio/workshop filled with tools, equipment, and materials. Lately I have begun to find this approach burdensome in terms of the resources it requires and the accumulation of physical objects that is its natural result. Therefore I have begun to make work that is immaterial and doesn’t require the infrastructure of a studio, like single channel videos, web projects, etc. These projects are working out for me and I am considering ditching my studio altogether. My question is: Can a contemporary artist expect to be taken seriously if he doesn’t maintain a studio? How might I deal with studio visits with curators/gallerists etc.? Am I being hasty and reactionary?

Many artists have gone through a sea change, abandoning one body of work in favor of something new. In 1970 John Baldessari famously burned all his early paintings and made work from the ashes before turning the bulk of his attention to appropriation and photography. Perhaps you are undergoing the same kind of transformation.

It’s not for me to say if you are being hasty and reactionary—that’s an issue you can puzzle out with the friends who know your practice and your work well enough to judge. In fact, it’s difficult to give you hard and fast advice without knowing exactly how you arrived at your decision to stop making sculptures and installation. You might be going through a phase, or you might be on the verge of a whole new life. How do you feel about commitment? If you like to change your style or job frequently, you might want to wait and see what happens before you dump your studio. If you’ve been rocking the same M.O. since high school and tend to follow a course for a long time, this might be an indicator that your days as a sculptor are truly over. Only you can decide if this is a long-term decision or a temporary state of mind.

John Baldessari, The Pencil Story, 1972-1973. Two B-Type prints on board with colored pencil

Can a contemporary artist be taken seriously without a studio? Well, it depends on what kind of artist you are. I can envision, for example, a social practitioner who claims the world as her studio, and I can see the curators of the next Documenta taking that kind of thing very seriously indeed. If your work is strong you can get away with a lot, and I think you could certainly make a case as a conceptual/non-material artist for not needing a physical studio.

But is there a middle ground here, even a temporary one? If you are making videos and want to show them to curators and gallerists you’ll need some sort of place to meet and talk. This could be a spare room in your house or a cleared-out corner of your apartment. You could also consider renting a small space in a large, shared studio or office where you could put a desk and chairs, a place where you could receive visitors without having to clean your bathroom and tidy up your living area. If you have an exhibition, ask the gallery if you can use the exhibition space as a meeting place during off hours. Then you can tour visitors through the exhibition as well as use your laptop or website to show them images of other work.

Perhaps you can put your tools and equipment into storage for a while. It’s cheaper than renting a studio and you can always go back to it if you change your mind. Like the box you never open after moving, if you haven’t gone to your storage space in, say, a year or two, you might feel comfortable letting go of what’s inside. Good luck.

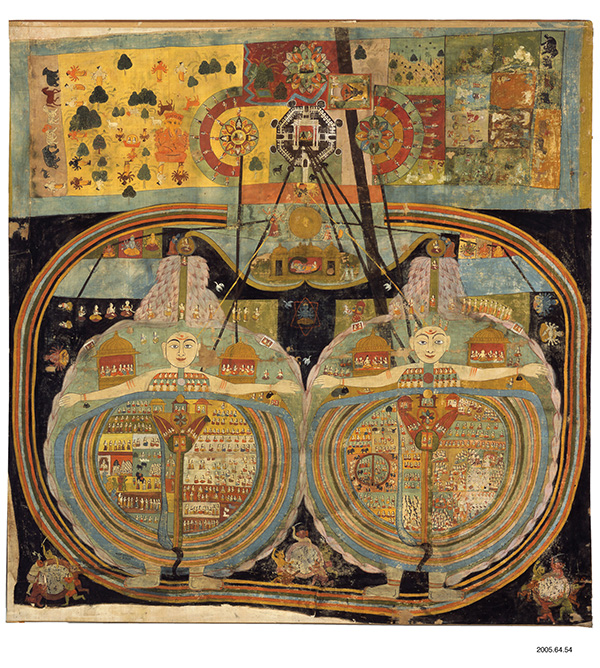

The first piece that caught my attention was Takayuki Yamamoto’s What Kind of Hell Will We Go. Takayuki presented a group of Bay Area children with a painting depicting the Japanese myth of hell, after which each young artist created his or her own hell narrative and accompanying diorama. While I do not think that all children’s art is great (sorry, moms and dads), there is an undeniably profound phenomenon that occurs when the unadulterated freedom of childhood confronts ideas like mortality, or good and evil. In one example, titled “Bad Word Hell,” the speaker of bad words is repeatedly burned and then thrown in with the sharks. The piece alludes to the way in which children cope with the things they learn about the world, and how those ideas can be treated playfully while also acknowledging their seriousness.

The first piece that caught my attention was Takayuki Yamamoto’s What Kind of Hell Will We Go. Takayuki presented a group of Bay Area children with a painting depicting the Japanese myth of hell, after which each young artist created his or her own hell narrative and accompanying diorama. While I do not think that all children’s art is great (sorry, moms and dads), there is an undeniably profound phenomenon that occurs when the unadulterated freedom of childhood confronts ideas like mortality, or good and evil. In one example, titled “Bad Word Hell,” the speaker of bad words is repeatedly burned and then thrown in with the sharks. The piece alludes to the way in which children cope with the things they learn about the world, and how those ideas can be treated playfully while also acknowledging their seriousness.