Los Angeles

Jack Goldstein’s Peaks and Valleys

Artist Jack Goldstein and his dog, 1986. Image copyright Peter Bellamy.

“Jack Goldstein is currently at work on a new film called “The Jump.” It is to be nineteen seconds long and will show a diver performing a somersault from a high board. But the high board and the water into which he plunges will be absent from the finished film…Goldstein is performing a set of operations that isolate, distill, alter, and augment the filmed recording of an actual event. He does this in order to impose a distance between the event and its viewers because, according to Goldstein, it is only through a distance that we can understand the world. Which is to say that we only experience reality through the pictures we make of it.”[1]

So begins Douglas Crimp’s famous 1977 “Pictures” essay, which introduced not just a show, but a movement of young artists determined to draw attention to and capitalize on the way images mediated the late 20th-century experience. Fittingly, “Jack Goldstein x 10,000,” at the Orange Country Museum of Art, also opens with the now-iconic film, which features the glowing red figure of a diver against an all black background. The diver bounces on the invisible board, twists, and disappears smoothly in the nothingness of the erased water. The motion feels effortless and also exhausting.

“Jack Goldstein x 10,000” consists of thirty-plus years of work. The early films that put Goldstein on the map as a member of the Pictures group are there (including “The Jump,” 1978, and “MGM,” 1975), as are several immersive sculptures, text works, and records—not to mention the enormous, black-and-white paintings of the ‘80s and the paintings that followed.

The main draw continues to be the films, perpetually repeating and acting as counterpoints to each other. “A Nail,” 1971, “A Glass of Milk,” 1971, and “A Spotlight,” 1972, play opposite “Jack,” 1973, (amongst others); we see the artist agonizingly and slowly pull a nail out of a piece of wood with his teeth, empty a glass of milk by pounding his fist on a table, and try to run away from a spotlight. In the same moment, we watch a cameraman slowly back away from Goldstein, step by step, until the artist is engulfed entirely by the landscape.

In the next room, Goldstein’s edits keep the famous MGM lion repeating its roar, and in the room beyond a foot in a ballet shoe collapses when the ankle ribbons are untied (“Ballet Shoe,” 1975); a china pattern of birds comes to life and circles a dinner plate, trapped (“Bone China,” 1976); a dog barks and barks and barks (“Shane,” 1975); a knife fills with reflected color, empties, and fills again (“The Knife,” 1975). As mundane and tedious as all these actions are, the tension is captivating.

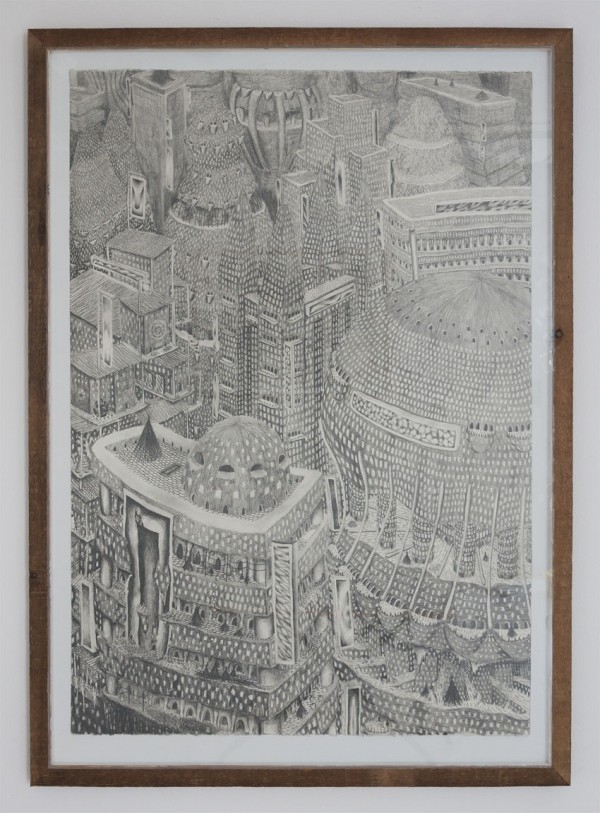

Much has been made of the fact that Goldstein used outside labor for his work, hiring animators for his films and using illustrators to complete the series of paintings that followed—wall-sized, black-and-white images of aerial raids, or the spectacular effect of lightning over Western skies. The technique allowed Goldstein’s conversation with his Pictures colleagues to continue; aesthetizing images of damaging events such as the 1941 bombing of the Kremlin. As Los Angeles Times critic Christopher Knight puts it, “It’s as if Goldstein’s photo-based works chronicle the upheaval caused by mesmerizing mass media, the daily blitz of modern life.” All with the hand of the artist removed.

From "Jack Goldstein X 10,000, "Untitled," 1981, acrylic on canvas. (Brian Forrest, Orange County Museum of ARt / July 12, 2012)

The exhibit wraps up with several abstract paintings that resemble thermal maps with the mapped object long gone, a more recent film in which Goldstein cuts between various sea creatures at the moment they pause in motion, and “Aphorisms,” written fragments presented as highly-designed images as well as less polished chunks of text that vary in between upper- and lower-case, bold and regular face.

On the whole, the exhibit is complicated and almost amorphous. Unlike his peer, Cindy Sherman, whose retrospective is currently on view at SFMOMA, Goldstein did not maintain one specific and particular focus or style. One can certainly map an obsessive fixation on time and nature, something obvious enough to be commented on but downgraded as a priority in the various conversations on Goldstein’s work. The exhibition pamphlet points out that much of the focus on Goldstein continues to be on his relationship to images and the idea of the spectacle, themes leftover from his association with Crimp and subsequent writing on the Pictures group. Honestly, what I see in “Jack Goldstein x 10,000” is an artist questing for his voice again after tiring of being stuck in the same loop. Unfortunately, we lost Jack Goldstein in 2003, but curator Philipp Kaiser provides a nuanced overview of his peaks and valleys.

[1] Douglas Crimp, Exhibition Catalogue, “Pictures,” Artists Space, New York, 1977.