New Orleans

Post-Fordlândia: A Critical Look at a Failed Development

Megs Morley & Tom Flanagan, “Interior American Village Fordlândia”, Lamda print, 20×31, 2011

Post-Fordlândia, the new exhibit at Good Children Gallery, is a palimpsest for modern times: it calls from faded pasts to warn us of an ill-advised future. A series of high-def videos and large format photographs, taken by Irish artists Tom Flanagan and Megs Morley, depict the now defunct and abandoned town of Fordlândia, the mad brainchild of Henry Ford. This experiment in urban and cultural planning for the benefit of Capitalism was built in 1928 in the Amazon jungle of Brazil in order to supply rubber to the Ford production plants in the United States. Flanagan and Morley’s photographs document the disaster of this town as riots and unrest left Fordlândia now a barren, post-apocalyptic wasteland.

Megs Morley & Tom Flanagan, “Plantation Factory, Fordlândia” Lamda print, 20×29”, 2011

Post Fordlândia is a small exhibit, made up of five photographs and two videos. The rich, lushness of the high-def shots make the videos the tours de force of this show. Morley cites French philosopher Jacques Rancière ideas on documentary film as a form of fiction as an influence in the structure of the films. In the video Fordlândia, twenty minutes of ephemeral spaces lulls the viewer into a hypnotized fascination. Imagined stories of the place and its inhabitants grow in the mind as the film progresses. Morley and Flanagan layer present day images and experiences over each other to reveal lost moments in time. Abandoned cities give the viewer the uncomfortable feeling of watching huge chunks of time happening at warp speed. As Peter Schedjahl pointed out recently, “Nothing spoils faster than the future.”[1] In this case, the past and the future seem to intermingle with uncomfortable ease.

Megs Morley & Tom Flanagan, “House, American Village, Fordlândia”, Lamda print, 20×29”, 2011

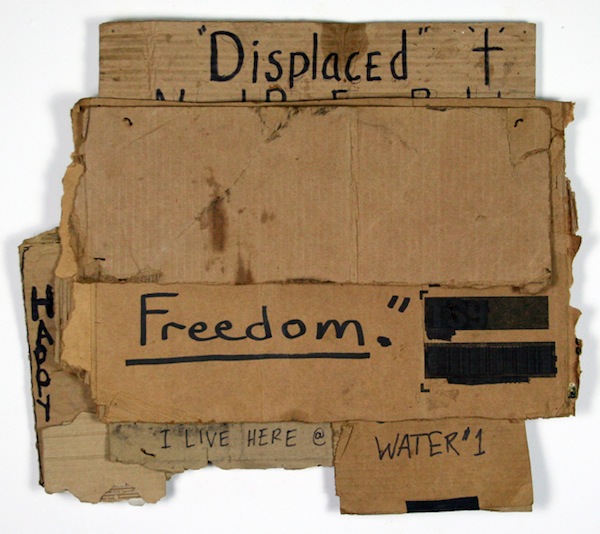

What is so interesting about this exhibit is that, when placed in the context of New Orleans, the images of an abandoned Americana are imbued with an ominous significance. Flanagan and Morley are collaborative artists working with Gallery 126, an artist-run coop based in Galway, Ireland. Malcolm McClay, a founding member of Good Children, is a native of Ireland and worked with Gallery 126 to bring these artists to New Orleans. He pointed out, “When I saw this exhibition in Galway I assumed Post-Fordlândia was Central or South America, yet when it opened at Good Children almost everyone asked me if it was New Orleans. It is a great reminder of how context profoundly affects the audience’s interpretation.”[2]

As New Orleans enters a new phase in its history, one of redevelopment rather than recovery, Post-Fordlândia reminds audiences that top-down cultural and urban planning are sincerely defunct practices. As large swaths of New Orleans are being knocked down to build hospitals and housing developments, one can clearly see the inherent instability of large-scale redevelopment. What happens to the culture lost during rebuilding? Will institutionally developed neighborhoods be adopted and provide cultural continuity or will Cabrini-Greenesque futures ensue? Owners of the 265 homes in Lower Mid-City razed through the Eminent Domain of the State to build a private hospital are unfortunate experiments in this test tube time.

By deciphering the lost history of Fordlandia, Morley and Flanagan present an alternative strategy, one of new criticism and skepticism regarding urban development. Long, poetic shots of Fordlândia’s empty factories and residences underscore not only the economic loss suffered by Ford (over twenty million dollars were lost by the Ford family when Fordlândia was sold in 1945) but also the loss of a physical space for those native to the region. These long shots are painful reminders of not just a recently empty city, but also a impending changes in the fabric of New Orleans as it becomes a bigger, brighter, slightly more sterile version of itself.