Hashtags

#museumpractices: The Museum On My Mind, Part II

Wall labels. Curatorial text. Provenance. Titles (or un-titles, as the case may be). At what point do the words surrounding an artwork serve the work, and at what point do they disrupt it? In terms of the museum, specifically, when do explanatory labels benefit museum-goers, and when do they detract from an individual’s experience? This week, #Hashtags features Part II of The Museum On My Mind, a meditation on the role of museum commentary and what it means to “know” a piece of art. Click here for a refresher on Part I.

Part II: Writing on Water

Famous for using chance operations to compose both musical scores and visual art, John Cage’s goal was not to manifest a “gratuitous” randomness,[1] but to put “the intention of the mind . . . out of operation.”[2] For Cage, non-intention was not unintentional: “If you work with chance operations, you’re basically shifting—from the responsibility to choose . . . to the responsibility to ask.”[3] Cage was influenced by the “whispered truths,” three principle tenets from one school of Zen Buddhism, including, “[Y]our action should be as though you were writing on water. . . . In other words, not to make an impression.”[4] Simple as the principles are, they signal the fundamental endlessness, evanescence, and wholeness that we camouflage with our attempts to limit, preserve, and distinguish experience.

Left: John Cage, Eninka 28, 1986; one in a series of 50 smoked and branded prints on gampi paper chine colle; 25 x 19 inches. Right: John Cage, Without Horizon 33, 1992; one in a series of 57 unique aquatints with etching and drypoint on smoked paper, 7-1/2 x 8-1/2 inches. Both published by Crown Point Press, San Francisco; courtesy of Crown Point Press.

“Writing on water,” whose activity is visible but whose product is not, suggests a method of commentary that acts as a medium rather a mediation—present but silent—and that almost invisibly carries the visitor through the exhibit. If afterward, the personal revelations of a visitor’s experience have obscured the visitor’s memory of the commentary, “commentary on water” will have achieved its goal of making no impression.

The Spirits That Lend Strength Are Invisible

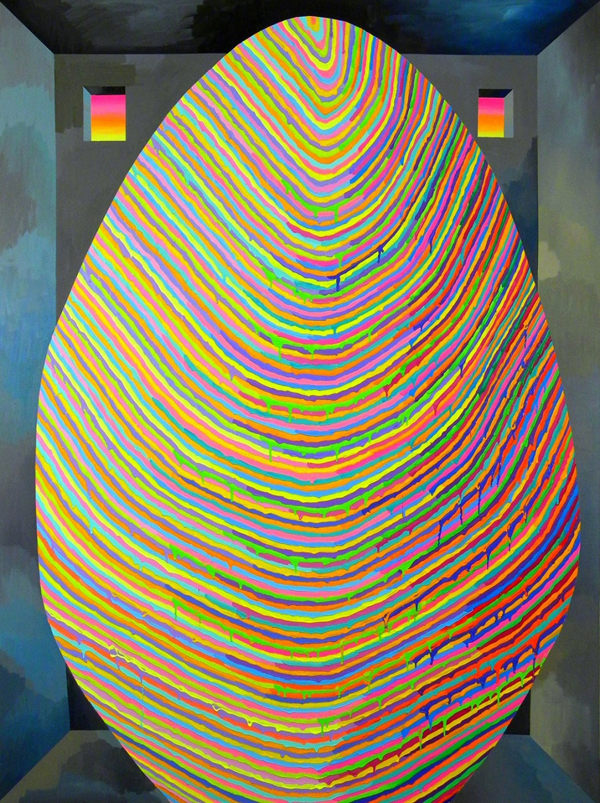

I come upon The Spirits That Lend Strength Are Invisible III (Nickel/Neusilber), Sigmar Polke’s 1988 painting at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. In my mind I see an image, but it’s really a feeling and it’s really in my gut: the expansion of the painting beyond its boundaries. Standing outside of it, I feel suddenly upon it, inside it, traveling through it. All of this happens before I come to the painting’s label.

Sigmar Polke, The Spirits That Lend Strength Are Invisible III (Nickel/Neusilber) (1988), painting, nickel and artificial resin on canvas, 157-1/2 in. x 118-1/8 in. Photos: Saul Rosenfield, ©2012, with permission of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Labels tell me what I might expect to “discover” in the artwork: Polke’s painting is a homage to American Indian culture, evoking both the sense of support, of strength, and the invisibility, the unknowableness, honored in its source proverb; and the image is changeable, its chemical process evolving, thus, time-altering. The language is clear and gentle,[5] but would I have felt as transported had I first read the label, whose words risk displacing—or, worse, standing in for—my experience? This is how the modern art museum has taught visitors to engage art—to frame experience with interpretation—but is the experience of art truly about the words that prepare the visitor for it? If a large part of what a person knows derives from the gifts of knowledgeable others, the part most likely to stick comes from—to paraphrase Cage—the questions that each of us asks during an entirely personal quest, and the answers each discovers during that quest.[6]