From the DS Archives: First-Person Reality: I Am Not Free Because I Can be Exploded Anytime

Today, From the DS Archives takes another look at Sterling Ruby‘s 2011 solo exhibition at Sprueth Magers in Berlin. Early next month Ruby’s work will be in a group exhibition titled Cellblock I & Cellblock II, curated by Robert Hobbs at Andrea Rosen Gallery in Los Angeles. Cellblock I & Cellblock II will also feature works by Peter Halley, Robert Motherwell, and Kelley Walker.

The following article was originally posted on April 20th, 2011 by Heather Van Winckle.

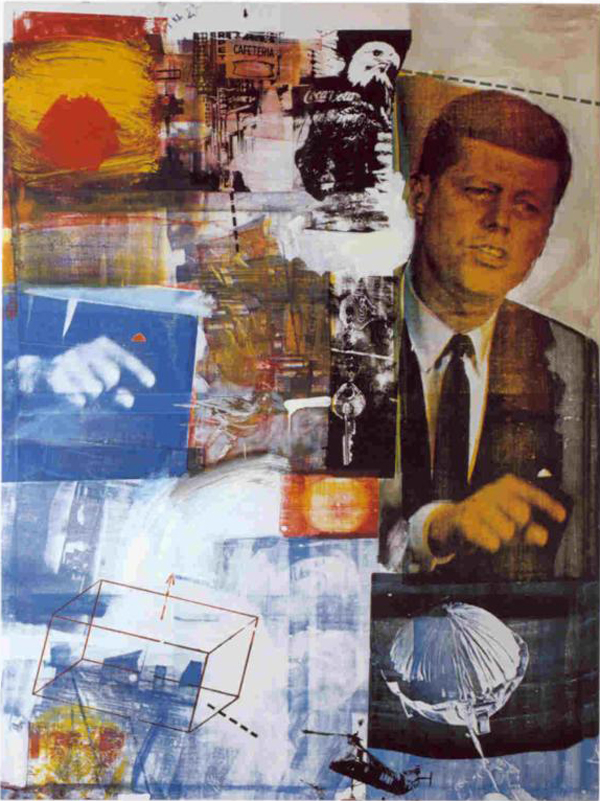

Installation view, 'Sterling Ruby. I AM NOT FREE BECAUSE I CAN BE EXPLODED ANYTIME', Sprueth Magers Berlin, 2011, © Sterling Ruby Courtesy Sprueth Magers Berlin London

The year is 1999. Television has adapted to the more violent nature of man.

Sterling Ruby‘s solo show at Sprueth Magers drops you into a space reminiscent of the real world, but reflected through an alternate lens. The main room feels overwhelming in scale, full of over-sized and crudely modeled ceramic sculptures, towering red dripping sculptures that look like some sort of giant animal’s tendons freshly ripped from its body, and spray-painted canvases hanging on the walls. As well, there are hanging fabric pieces in the shape of drops that both mock and confirm violence with their suggestion as blood drips in such a comically literal fashion.

Sterling Ruby SP151, 2010 Spray paint on canvas 125 x 185 x 2 inches 317.5 x 469.9 x 5.1 cm, © Sterling Ruby Courtesy Sprueth Magers Berlin London

The most popular form of television remains the game show.

The video game Wolfenstein 3-D (1992) introduced gamers to a three-dimensional environment where the camera is your eyes, a now popular point of view with the proliferation of first-person shooter games. Ruby’s spray painted blocks and wall hangings seem to reference the aesthetic of these 90’s video game graphics that place the viewer in this familiar world where you’re still a normal human, but, due to technological limitations, non-essential information, such as concrete walls, aren’t highly rendered. This room is quiet, and the suspended animation of the fabric sculptures puts the situation on pause. It’s calm, but horrific, as if your character has just faced an incredibly dangerous situation and through violent acts, defeated the level. Instead of moving to the next environment however, you’re suspended in this room to examine all of the carnage that has been created. While Wolfenstein and its ilk were often criticized for their violence, there was at least a noble purpose for the bloodshed. The player, the narrative’s clear protagonist, was forced to deal with the situation placed upon him. That sense of urgency is not apparent here, as if the violence has no purpose.

One show in particular has dominated the ratings. That show is Smash T.V. The most violent game show of all time.

Two lucky contestants compete for cash and prizes. Each contestant is armed with an assortment of powerful weapons and sent into a closed arena.

In a first-person game, instead of pressing buttons to make an avatar respond from a distance, the line between reality and the game’s universe is blurred as the player is sharing a pair of eyes with the avatar. When a trigger is pulled, the bullet blasts out from in front of you, and in some cases, due to technological advancements made to heighten the game experience, you can feel a rumble or a recoil as the shot is fired. Your character didn’t shoot as you watched from the god perspective, you made the kill. Ruby argues that we don’t need these alternate worlds to tell us to be violent. By presenting this aesthetic in our real space, the over-the-topness of video games is used to highlight far worse atrocities of man that we regular people may ever have to encounter. In a world where wars are sold with technologies that are meant to separate us from the violence we cause, the hyper-violence suggested in Ruby’s shows drags back the more personal connection linking the offenders and the victims.

Installation view, 'Sterling Ruby. I AM NOT FREE BECAUSE I CAN BE EXPLODED ANYTIME', Sprueth Magers Berlin, 2011, © Sterling Ruby Courtesy Sprueth Magers Berlin London

Nowadays, simulated experiences are, if not completely believable, able to pique and maintain our interest while allowing us to play out fantasy scenarios that we may not want to carry out in reality. The problem comes when these simulations are based on reality and these traumatic and horrific scenarios do exist in our world. In Ruby’s show, it is as if our fused eyes have been pulled from this structure where our sole mission is to defeat the bad guys, into the complex ‘real world’ full of grey areas and complicated matters. This environment within the confines of the gallery, has all of the gore, but none of the background information or context. The entertainment value of gameplay has been stripped away, forcing us to acknowledge the reality we exist in.

The action takes place in front of a studio audience and is broadcast live via satellite around the world.

Video games are violent and make the players of them violent. While the validity of this statement is highly contested, that’s a common argument anytime a kid decides to bring a gun to school and take out his aggressions on the student body. The assertion is that once we find out how fun it is to see something die at our hands in a simulated situation, we are going to get a taste for blood that we need to quench in the real world.

Be prepared.

The future is now.

Sterling Ruby Monument Stalagmite/Survival Horror, 2011 PVC pipe, foam, urethane, wood, spray paint and formica 216 x 63 x 36 inches 548.6 x 160 x 91.4 cm, © Sterling Ruby Courtesy Sprueth Magers Berlin London

Ruby’s show seems to be the antithesis of the much discussed videogamafication of military operations in the media since the first gulf war. He takes the look of the hyper-violence that is all but commonplace in our media and makes one ‘level’ out of the gallery space. When your reality is like the virtual world, and you a video game character, a sudden shift in what is deemed an acceptable violence level tends to occur.

You are the next lucky contestant.

Italicized and bolded headings are quotes from the opening cutscene of the videogame Smash T.V. (1990)