For this edition of Fan Mail, Iavor Lubomirov of London has been selected from our worthy reader submissions. Two artists are featured each month—the next one could be you! If you would like to be considered, please submit your website link to info@dailyserving.com with ‘Fan Mail’ in the subject line.

What kind of elation do you get from your study of mathematics? You have taken a journey from studying mathematical systems to producing unique visual analyses of that data. How might you square up the concept of free will with a seemingly deterministic universe?

Mathematics to me is an expression of the inner workings of our animal thought machine. It can do things like laugh and catch a ball and we know why, to some small immediate extent, and with mathematics we glimpse a little bit of the how. A tiny tiny tip. We humans know so little mathematics, though it’s ever so much. To me, mathematics does not have that deterministic quality which it is standard to associate with it. I see the fuzziness in its structure. At its core it is based on a notion of duality – things are or they are not – and I believe, or rather feel, that reality quite comfortably exists in contradiction, that this is not the exception but the rule. The ancient Platonic conception of the perfect mould in heaven and the imperfect instances of it on Earth to me is entirely the reverse of reality. Perfect objects are intensely complex and human attempts to simplify them produces imperfect shadows in our minds, which we call logic. So for me there is no dichotomy between determinism and free will. They are two faces of a hugely complex shape.

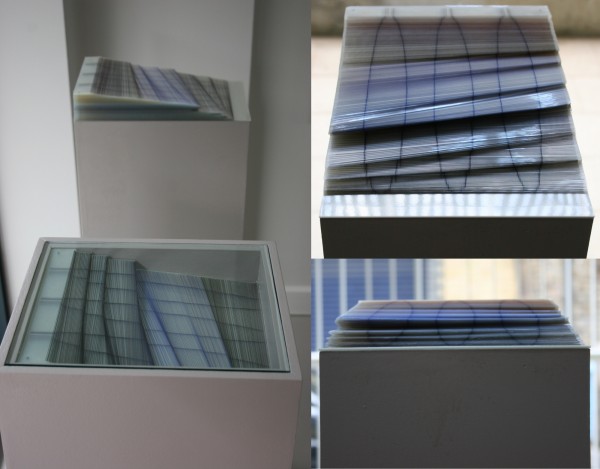

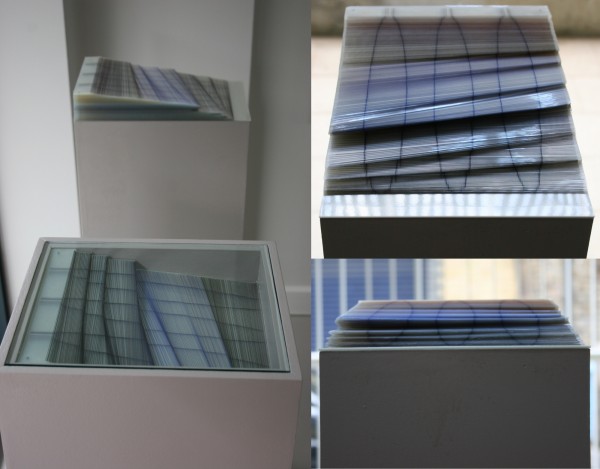

Iavor Lubomirov, Three-Phase Cylinder I & II, 2012, 100 Micron Clear Film 21 x 27.9 x 4.6 cm.

“The origin of conic sections is unknown – the earliest reference we have is in the work of Apollonius of Perga around 200BC. Traditionally, Apollonius and the spate of mathematicians who followed in his footsteps over the centuries, used a cone sliced by a plane to define the circle, ellipse, parabola and hyperbola. Three-Phase Cylinder departs from the reductivist approach used to isolate these regular shapes and instead flirts with the methodology itself, letting a whimsical curling plane (mathematically defined by oscillating trigonometric functions) intersect three regular cylinders to produce a mathematically inutile set of shapes.”

This method of playing with a shape in physical reality as a means to grasping some mathematic complexity before it was written symbolically shows how these generalizations are functional and elegant. It reminds me of a trip that I took to see Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia church in Barcelona earlier this year where I saw Gaudi’s method of understanding the form and load-bearing capacity of his arches by making upside-down string models hung with weights. It allowed complex mathematics to be used and understood in a simple and direct way.

Iavor Lubomirov, Ersatz Biblical Synaesthesia, The First Book of Moses called Genesis, 2012, Giclée Print on Hahnemühle 21 x 27.9 cm.

“The works are composed by a computer program which processes the numerical ASCII codes of the characters in the English text. The program uses a bespoke logic to convert the resulting numbers into hexadecimal RGB colour codes, with which it colours a square digital image pixel by pixel. A typical Old Testament book will contain around 200,000 characters, resulting in a seemingly random, highly pixelated image, which nonetheless is a faithful rendering of the King James text. The fact that a human will not be equipped to ‘read’ this visual text is an important comment on the nature of translation and the long history of a text which has so often been inaccessible to people whose lives were nonetheless deeply affected by its substance, interpretation and political appropriation.”

I imagine that you must enjoy the detail and tedium of your works–some artists might say it brings them to a meditative state–do you have that kind of spiritual component of your life? In light of your ‘Ersatz Biblical Synaesthesia’, I’m curious to know what kind of beliefs you hold about religion, Christianity, spirituality, and/or the mind/body problem. The content of ‘Ersatz’ seems to be the mutability and evolution of these texts through translation.

Going on to religion, spirituality and existence, I find myself a bit overwhelmed as to how to begin to answer such a complex and rich matter. I have read a lot of historical and scientific texts on Christianity – both about the small Jewish sect founded by Jesus under Roman occupation of Jerusalem and about its later transformation into a European spiritual religion, primarily through the early writings of St. Paul, who brought us the myth of the resurrection. I have also made some researches into Islam and to a very small extent Hinduism and Buddhism. What interests me in the major religions is their influence on the overwhelming majority of contemporary world society, which can remain enmired in these early and simple forms of human philosophy even while living in an age of radically evolved understanding. Reality is of course immeasurably grand, inhuman and terrifying – much more so than a vision of a universe ruled by a compassionate and essentially human maker. I don’t deny god – that would be arrogant indeed. But nor can I seriously allow myself to believe in medieval and ancient conceptions of what god is and which have been shaped for centuries by the political and philosophical conveniences of their day.

Iavor Lubomirov, In Hind Sight, Fabriano Watercolour Paper, 2006-2009.

“‘In Hind Sight’ considers objects in 4-D space (3-D space with time) and tries to show them from a new visual perspective. Its starting point is a video of a 34 second movement performed by two artists in an empty space and filmed at 25fps. The video was decomposed into 850 individual stills, each was cut out of paper and the whole was then assembled.”

A work such as ‘In Hind Sight’ seems like it would take quite a lot of work to cut by hand and the edges are so perfect.

It took me over a year to cut and assemble ‘In Hind Sight’, with some more and some less intense periods of work. The hardest part is finding the time to indulge such an inexplicable activity. One might expect that it would be the tedium of cutting – which you perceptively see as a source of joy rather than pain – but this in fact is largely mitigated by the observation of the slow evolution of the work and its many beautiful hidden moments, which are revealed and then obscured by the process.

Upon first viewing ‘In Hind Sight’, I saw what immediately resembled a Chinese lion dance costume to me. The analysis of two bodies in motion is not something I would have guessed from looking at the work, but that content was there in an intuitive way. How did you deal with the negative space between the figures—did you need to smooth out the lines to make it work?

The negative space in the piece is accepted honestly and there is no trickery designed to evade it. Some of it is hidden inside the work. Other negative spaces simply make it quite fragile in totality. The two dancers worked very close to each other in a confined room, so they did not create very large gaps between their bodies for this short piece.

Your ‘Prototype for a Romance’ brings back an architecture space from a 2-D rendition into real space. The collaborative process and the meeting of two minds is like a romance. We can never unify or see through another’s mind but we insatiably try.

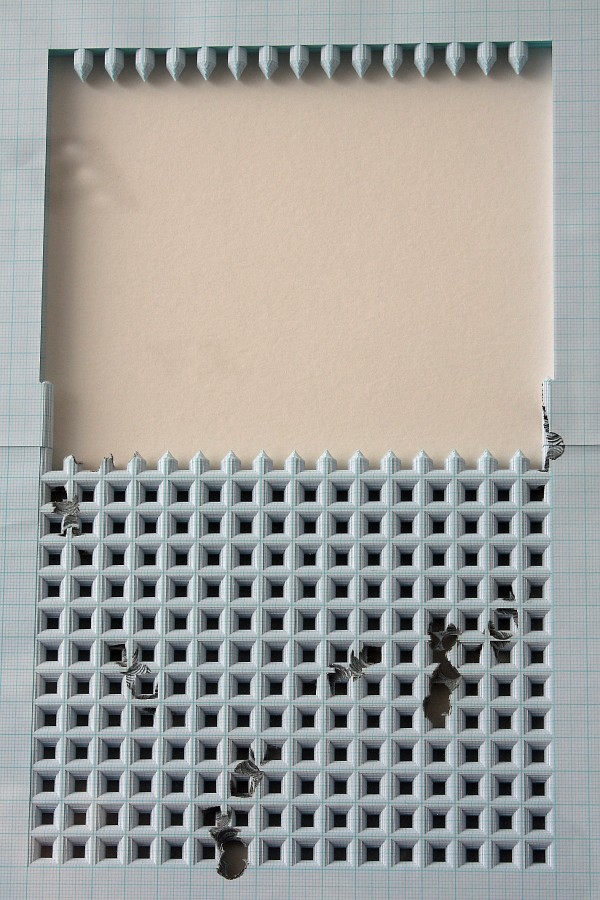

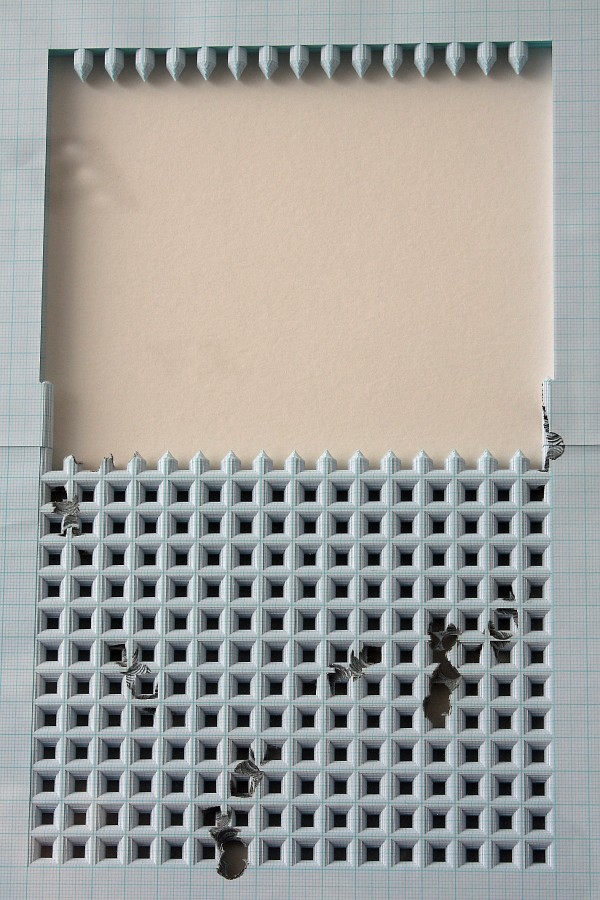

Iavor Lubomirov, Prototype for a Romance in Many Dimensions, 2012, Multiple Giclée Prints on Card Four pieces, each 21 x 27 cm.

“This series of four architectural works is a prototype for a planned collaboration with painter and printmaker Bella Easton. It was created by hand, using 359 identical prints of Easton’s ‘Rule 174′….Lubomirov and Easton take calm stock of the visual and compositional purpose of the grid established last century. They accept its validity as an overt presence…” Bella is currently creating 180 finely graded prints which I will shape into a sculpture.

Your website suggests that the grid is a kind of scaffolding for art rather than a constraint. It makes me wonder about your relationship to the landscape in general. A sense of place is often defined by our artifacts, and when considering the grid, I think of the city laid out over the land, and the grid is a structure that makes a vast city comprehendible and navigable. But there are layers of landscape before/below/inside/above the grid. The grid has a capacity to wipe out history or to let a place evolve and learn from itself in a strategic way.

Iavor Lubomirov, Heliothis.zea, 2007-9 graph paper 45x55x3 cm.

“In the gallery, the work was placed on a small white desk, into which a rectangular hole was cut, very slightly larger than the grid in the pad. Thus, when a viewer sat down to examine the graph pad, they were able to see their own legs through it and through the desk.”

Iavor Lubomirov, Schema for a New Grid System (Liverpool), 2008, graph paper 45x55x3 cm (installation view).

I missed your question about my relationship to the landscape. To me it is incidental. Fishes swim in the sea, birds in the air, worms in the earth. Crabs and humans crawl about on the bottom and occasionally look up. Each substance is a sea and a landmass, depending on your own incidental density and the speed of time. If you put a piece of lead on the ground and speed up time so that a thousand years is like a second, you will see it sink down like a rock thrown in the sea. You see these old houses with stone fences that lean after a hundred years and you realize that they have been built on mud and are floating and bobbing on top of it. Everything is fixed and in constant flux too. Time is just a dimension. Nothing ever disappears.

Iavor Lubomirov was born in Bulgaria completed his degree and Masters in Mathematics at Oxford University in England and his BA in Fine Art at University of East London. Part of his ‘Three-phase Cylinder’ will be on show at the all inclusive CGP Gallery Open show opening on Sunday, November 11th. His selected solo and group exhibitions include: Vegas Gallery (2012), Angus-Hughes Gallery (2011), The Magnificent Basement (2010), August Art Gallery (2009), Calvert 22 (2008), Liverpool Independents Biennial (2008), and The Royal Academy Summer Exhibition (2007). Iavor is a co-founder of the art network ALISN, supporting emerging artists in the UK and abroad. In 2012, with painter Isabella Easton, Iavor opened the Lubomirov-Easton Project Space.