Best Of 2012 – Weaving, Not Cloth: Mark Bradford

Most of you know of Bean Gilsdorf as the author of DailyServing’s popular art advice column, Help Desk. However, occasionally Bean will step away from Help Desk to contribute an interview, article, or review. Today’s Best Of 2012, Weaving, Not Cloth: Mark Bradford, was written by Bean Gilsdorf and selected by DS contributor Emily Macaux.

“In Weaving, Not Cloth, Bean offers a nuanced and penetrating treatment of Bradford’s work, conveying its material richness and extraordinary tactility.” -Emily Macaux.

——————————————————

The difficulty in viewing photographs of artwork is that the camera flattens the object in its focus, relinquishing subtleties in order to capture a whole. Because his oeuvre is very subtle indeed, Mark Bradford’s work requires a viewer’s presence to be fully appreciated. Very little of the slender lines of collage, delicate papers built up in thin layers or washes of paint almost completely sanded away is apparent in reproduction. Each of the more than forty of Bradford’s works now on view at SFMOMA calls out to be felt, if not by the hand of the viewer then by the eye. They elicit a state of tactile vision, a reminder that visual perception is also connected to the faculty of touch.

Mark Bradford, Potable Water, 2005; billboard paper, photomechanical reproductions, acrylic gel medium, and additional mixed media; 130 x 196 inches; collection of Hunter Gray; © Mark Bradford; photo: Bruce M. White

In the scholarship regarding his work, much has been made of the condition and location of Bradford’s studio practice. He grew up (and still lives) in South Central Los Angeles, a mainly black neighborhood mythologized for its urban decay. Bradford worked at his mother’s hair salon before attending art school, learning skills that he would adapt to his practice: hard work, repetitive actions and tactile processes. He gleans his materials from the posters, billboard papers, and hair salon permanent-wave end papers that are still part of his environment. And while all this information surely contributes to an important analysis of his work based in socio-economics, race and culture, it ignores the physicality and lushness of the actual surfaces and the connection of Bradford’s work to textiles.

Mark Bradford, Value 47, 2009–10. Billboard paper, photomechanical reproductions, acrylic gel medium, carbon paper, nylon string, and additional mixed media on canvas; 48 x 60 inches; courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York; © Mark Bradford; photo: Fredrik Nilsen

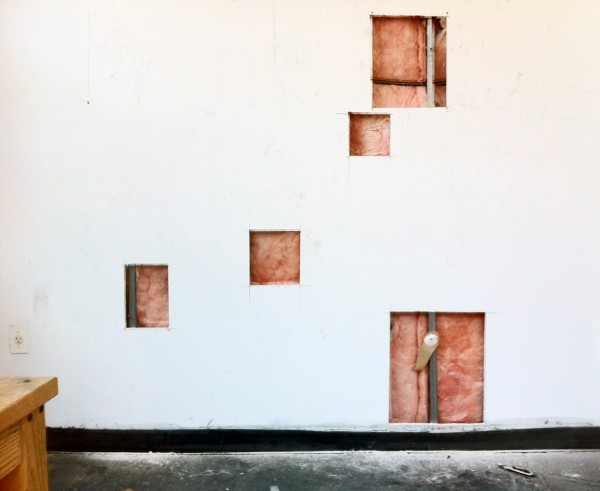

Up close, the dense materiality of each piece intrigues with a kind of sumptuous dissolution; there is tension between order and chaos, rigid geometries and decay. Layers and layers of papers and paint built up over time manifest the tactile nature of his working process, while the sanding between layers wears away the visible to the point of ruin. Each surface affirms Bradford’s physical presence, because these are techniques that can only be achieved by putting sinew and muscle in service of production. Though he calls them paintings, Bradford’s work more precisely exists in the productive space between painting, collage, and textiles. Many of the smaller and mid-scale collages are built on stretched canvases, allusions to the image-framing and containment of the traditional painting. However, several larger works are created on unstretched canvas that adds a layer of dimensionality to the form. For example, the surface of You’re Nobody (Til Somebody Kills You) undulates like fabric—it’s not really flat at all—and the edges are ragged and crusted with cracked paint. Though I include a photograph of the work below, the camera fails to capture the tangible thicknesses at the edges of torn papers, the white areas sanded smooth, the divots and pockmarks in the grids, or the directional marks of a brush dragged through thick gel medium. These surfaces create the haptic character of the work.