From the Archives

VERSUS

In this week’s “From the DS Archives”, we link two photographers’ projects which discuss the relationship between a son and his parent, and coping with the effects of age on the brain and the renewed relationships between aging parents and their aging children. Joshua Lutz’s new show “Hesitating Beauty”, which opened April 11th at Clampart, with a new monograph of the same title, creates an intensely intimate portrait of the artist’s mother, whose mental illness dissipated with the onset of dementia. In a similar vein, today we revisit the work of Phil Toledano, whose work has been covered in Daily Serving here and below. A piece from his project “Days with my Father” is pictured below.

The following article was originally published on January 28, 2010 by Allison Gibson

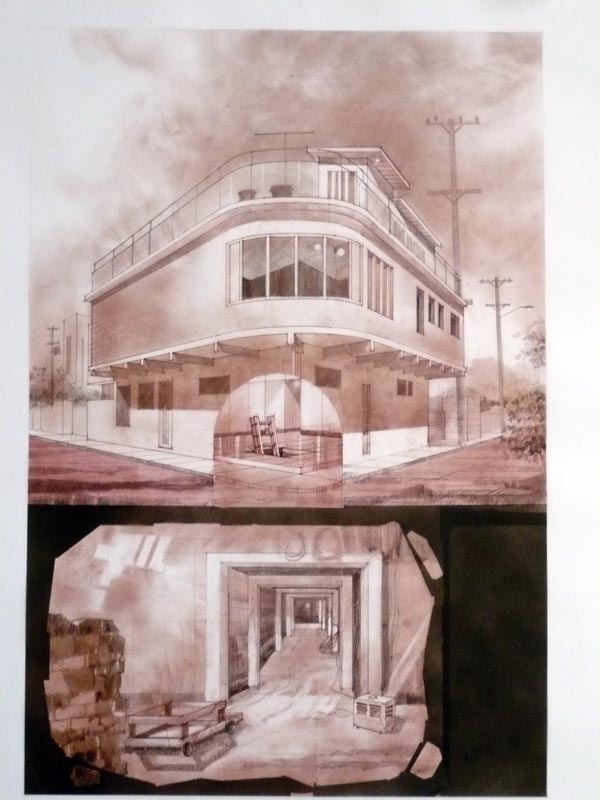

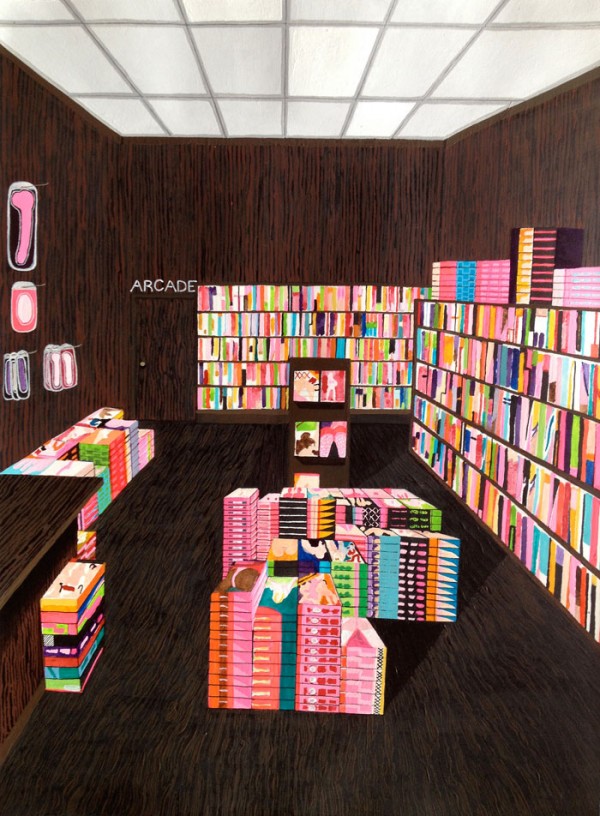

Currently on view at Hous Projects in New York is the exhibition Versus—a unique sort of survey featuring 18 seminal photographers of our time. Curated by Ruben Natal-San Miguel, whose work is also exhibited in the show, Versus pairs these emerging and established contemporary photographers with one another according to similarities—and striking contrasts—in subject matter, theme and aesthetics. The photographers explore ideas of ideal beauty, subjects of idolatry in America, relationship dynamics, juxtaposing stages of life and architectural and environmental moods. Some of the comparisons and contrasts between the paired photographs are more subtle, while other times the images seem to mirror one another. The visual motifs presented by the photographs on view are equally striking. Deep shadows conceal some scenes while others employ repetitive pattern to contrast with meek looking portrait sitters.

Ty Ennis,

Ty Ennis,  Ty Ennis,

Ty Ennis,