New York

Alone Together: Newsha Tavakolian at Thomas Erben Gallery

“We are all so much together, but we are all dying of loneliness.”

This quote by German theologian Albert Schweitzer captures a universal truth about the human condition, but its poignancy is particularly acute for city dwellers. Feeling lonesome while contemplating the vastness of the ocean or looking at the night sky is one thing; feeling isolated while surrounded by a crush of people on a packed subway platform or navigating a crowded sidewalk is quite another. The presence of all of those unfamiliar bodies—millions of unconnected souls coexisting in such close contact—only intensifies one’s psychic isolation.

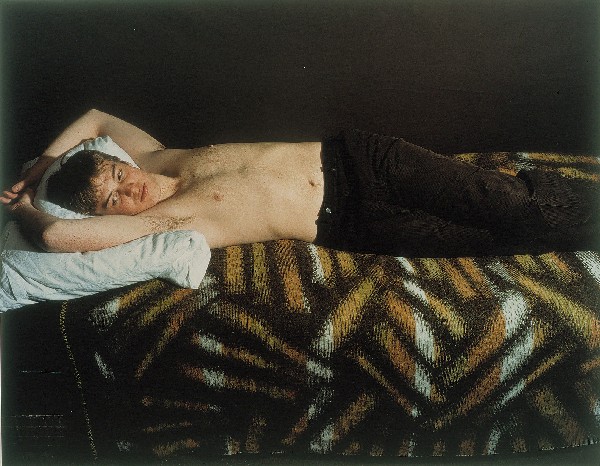

Newsha Tavakolian, “Look,” 2012. Inkjet print, 41 x 55 in., courtesy the artist/Thomas Erben Gallery

Look, the most recent series by Iranian photographer Newsha Tavakolian, personalizes this pervasive urban phenomenon. Currently on view at the Thomas Erben Gallery, the exhibit features large format portraits of Tavakolian’s neighbors in the Tehran apartment building where she has lived for the past ten years. Though the residents have spent significant time in close proximity—riding the same elevator, sharing the same view out their wide picture windows—they remain strangers. In its relentless documentation of individual solitude, Look serves as a contemporary, Iran-specific take on a classic modernist subject: the isolation and alienation of urban life.

“I wanted to bring to life the story of a nation of middle-class youths who are constantly battling with themselves, their isolated conformed society, their lack of hope for the future and each of their individual stories,” Tavakolian notes in the exhibition’s press release.

The framing of the photographs emphasizes what is shared among their young middle-class subjects. Shot over a period of six months, the portraits are almost identically composed. Each subject sits alone in the center of the frame before large wall-to-wall windows, which give out on a view of monolithic high-rise apartment buildings. Taken at 8 pm, as evening falls and the sky darkens, the photographs are infused with a cold, bluish light. Almost half of the subjects appear to be crying.

Newsha Tavakolian, “Look,” Installation view, courtesy Thomas Erben Gallery

Tavakolian’s project is driven by her desire to illustrate the difficulties of daily life in modern Iran. In response to President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s ongoing nuclear program, the US and the UN have imposed harsh new rounds of economic sanctions over the past three years, many of which specifically target the nation’s highly profitable petroleum industry. As a result, Iran has been plagued by high rates of unemployment and hyperinflation, and soaring prices have limited supplies of basic foodstuffs and medications. Despite unprecedented access to technology—several of Tavakolian’s subjects are shown with smartphones—Iran is increasingly cut off from the rest of the world.