Help Desk is an arts-advice column that demystifies practices for artists, writers, curators, collectors, patrons, and the general public. Submit your questions anonymously here. All submissions become the property of Daily Serving.

I’ve been meeting with a commercial gallery in my city for some time, and they’ve extended me an offer to come aboard. I’m excited about the idea of professional representation, having a platform to promote myself to a larger audience, and further opportunity for sale of work. I feel strongly about some of the work the gallery represents, but some of it is totally not my style, which is to say, artwork that favors more commercially viable subject matter or style at the cost of exercising any real dynamic or conceptual verve. How much should this influence my decision to join the gallery? I think deep down I’m afraid my work may be negatively evaluated against some of this work in question, and will affect my just-budding career moving forward. How crucial is it that a potential gallery fully affirm your conceptual ideal as an artist?

This is a great question, one which I am definitely not qualified to answer. Accordingly, I sent this query to a half-dozen represented artists and below are the replies I received.

Despite the fact that these artists are speaking from viewpoints all along the career continuum, their answers overlap considerably. They range from mid-career artists with New York and international representation plus several important museum shows, all the way to an artist in a second-tier city who has been represented for less than a year. I vowed to protect the identities of these artists in exchange for their candid replies, but I would like to thank them here for their thoughtful contributions.

-BG

* * *

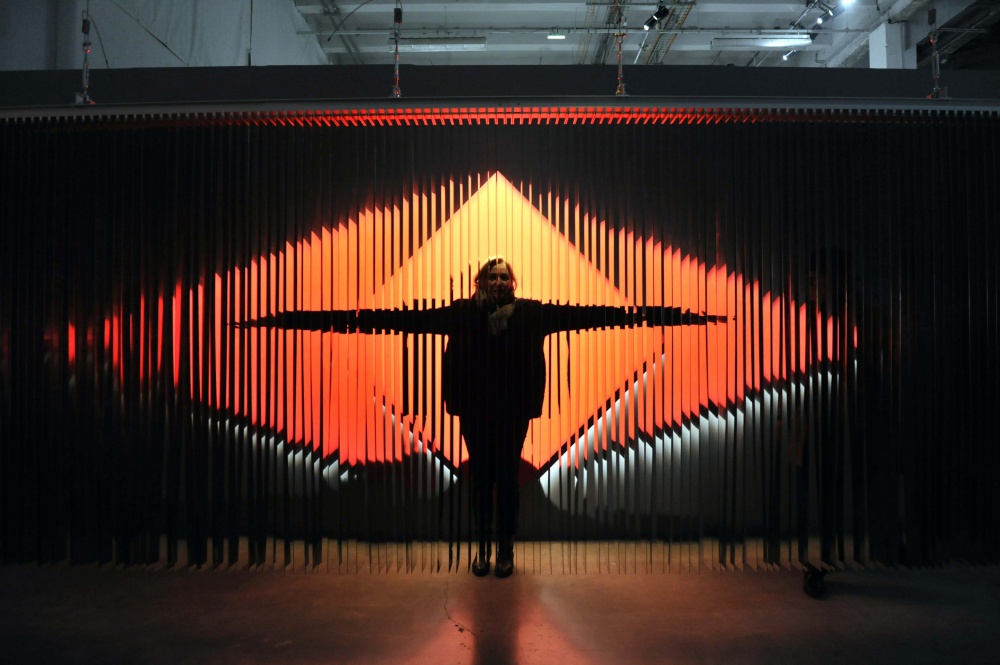

Lothar Hempel, installation view of “Cafe Kaputt” at Gio Marconi Gallery, 2009

This is a legitimate concern, but it’s only one among a number of questions an artist should consider when deciding to work with a gallery. It’s certainly important to feel as though your work and the gallery’s program are in sync, but that consideration exists in a nexus with other issues of equal or greater importance. First and foremost among these might be, do you like and respect the people running the gallery? Do you trust them, feel that they understand your work, and that they are both interested in and capable of promoting it in a way that will advance your career? Do you feel that they understand the business, and have done well for the other artists that they represent? Do you know any of those artists, or talked with them about how they feel their career is doing? Remember that you are entering into a business partnership with these people, possibly for an extended period of time. Do you have a clear sense of what your expectations and theirs are regarding this relationship?

Bear in mind that it’s generally unlikely that you will love all the gallery’s artists. If you like/respect/are excited by at least half the artists represented, that’s probably the best ratio you can hope for. A gallery is essentially a retail store, selling a very rarefied product to a capricious clientele. If the owners of the gallery make all their money solely from the gallery’s sales (as opposed to coming from a lot of money, or generating the bulk of their income from selling on the secondary market) they will almost certainly have to diversify their inventory, especially if they are based in a city without a strong collector base. While it is to be hoped (and should be expected) that a gallery “stands behind” every artist that they represent equally, the reality is also that there are some artists a gallery works with not because the work is especially cutting edge, but because the owners know they can move it and thereby pay their bills. (If you want a window into what this looks like, try watching the movie “Untitled,” which, while far from great, depicts some of these interior art world mechanisms at work). In other words, the presence of some artists will lend credibility and “edginess” to a gallery’s roster, while others may make sure the rent gets paid.

* * *

Pay attention to how conceptually aware and involved the gallerists are. If they seem to be supportive of your practice and any risks you might take with your work, that could trump what other more commercial work they might represent to keep the lights on. However, if you feel that they could stifle your drive, or set limits to your work, or get in the way of what makes your art something you feel is conceptually brave and forward thinking, then you should re-evaluate the agreement and possibly very cordially end the conversation. It’s good to see these opportunities as steps toward something greater, and if you are given free reign and a platform of exposure, it could be very beneficial down the road. It is smart to be mindful of these decisions though, because if you find yourself hemmed in and next to work you don’t respect, that can only lead to artistic and professional frustration.

* * *

Lothar Hempel, installation view of “Cafe Kaputt” at Gio Marconi Gallery, 2009

This topic has confronted me before—in general it’s a pretty common discussion amongst artists with commercial representation. Generally, galleries have to maintain a roster of artists that differ from each other in order to cater to a range of potential clients. So some artists on the roster may be considered more “commercial” or easily sold than others, or the artists may appear to be diverse and not necessarily relating to each other. But that’s not necessarily a bad thing—I’ve had several gallerists tell me that some of the artists they represent are considered the “bread and butter” ones—the ones that sell well and thus support the ability to show or represent the other artists who are less commercially viable but whose work the gallery wants to support for other reasons. Overall, you just want to make sure that the gallery you work with has a taste that you resonate with in general and that if push comes to shove, they can speak about your work in an enthusiastic way without you having to be there. Perhaps not all the artists in the roster are to your liking, but that is a common situation. If you think the gallery has BAD taste however, then by all means run in the opposite direction.

I have left a gallery before that I felt was not in line with my work, and it took a while to come to that decision because it was a very respectable blue-chip gallery. But in the end I wanted to work with a smaller, perhaps scrappier gallery because I felt their roster better reflected my own concerns of politics and social issues. There are definitely artists in the current gallery’s roster that I don’t care for, but I let that go because I know [the owner] works hard for me and represents me well.

I suggest that artists resolve this issue for themselves by asking several questions:

-Does the gallery you are considering seem to thoughtfully pick their roster of artists, or is it a hit-or-miss affair?

-Can the gallery understand what your work is about and represent it lucidly?

-Can you identify what the gallery’s “taste” is, and understand why they choose their artists?

-Will you cringe or feel embarrassed when asked who your gallery is?

-Do the other artists appear so “left field” that your peers will wonder why you are showing with them?

-Will it confuse clients as to why you are with that gallery?

-Do you feel comfortable showing up to the openings of the other gallery artists to support them and the gallery?

If this is all too much and you don’t feel enthusiastic, then it is best to wait for better representation to come along. If you are working hard and making good work, this is not your only shot at working with a gallery.

* * * Read More »