Today From the DS Archives we bring you a piece written by Daily Serving’s new managing editor, Bean Gilsdorf, from her weekly column “Help Desk.” Although only eight months old, the subject matter of her entry “The Social Disease” is still fresh. Featured in the article is work by artist Justin Kemp whose collaborative group Jogging has a new exhibition “Soon” at the Still House in Brooklyn, on view May 24- June 14.

This article was originally published on September 3, 2012 by Bean Gilsdorf.

Help Desk is an arts-advice column that demystifies practices for artists, writers, curators, collectors, patrons, and the general public. Submit your questions anonymously here. All submissions become the property of Daily Serving. Help Desk is cosponsored by KQED.org.

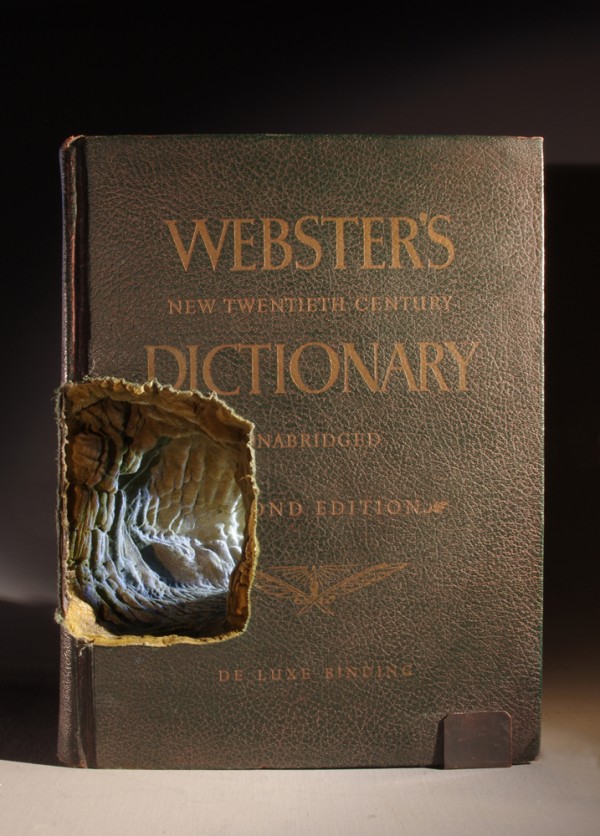

This week’s column features the smart, funny work of artist Justin Kemp (in particular, I love his adding to the internet project, which was too big to be included here). I found his work on the Rhizome ArtBase,”an online home for works that employ materials such as software, code, websites, moving images, games and browsers towards aesthetic and critical ends.” Check it out!

I have never approached a gallery or reached out to the art world beyond maintaining a basic website because I haven’t had a body of work I felt the least bit thrilled with–until now. Meanwhile, my best friend–a successful radio morning-show guy–spent the wee hours of his recent 40th birthday accusing me of being an ivory-tower artist and insisting that I was insane not to be promoting myself on Facebook and other social media. Any defense I could mount sounded elitist and snobby despite my best intentions. It’s been a few days and I’m still having a hard time articulating my reservations. On the one hand, of course I want vast numbers of people to see my work for its own sake and make of it what they will. On the other hand, I am repulsed by the idea of jumping into the public pool just because all the other lemmings did, naively unconcerned with the ramifications of having their lives irreversibly put on public display, just to play trite ego-games in an environment controlled by big business, monitored by government, and all of it propped up by nuclear-energy-guzzling machines made in places with questionable labor and environmental practices, whence they ultimately return on toxic waste barges.

Leaving my paranoia aside, I also feel that an artist today would do well to cultivate a little mystique. Despite my friend’s imploring to the contrary, I feel that yes, I will indeed be somehow rewarded someday for not succumbing to social media, because I feel that a gallerist wants to be the discoverer of the artist as a diamond in the rough, and how can you “discover” someone who already has 3,000 “likes” or “friends?” Am I an e-prude?

Golly. I can’t tell if you’ve come to the absolute right place or the wrongest of wrong places for an answer. Like you, I’ve eschewed most forms of social networking, and while I’m maybe not quite as paranoid (at least on the good days), I do share some of your concerns about privacy and what you winningly call “ego games.” So my answer might be a little bit preaching-to-the-choir, but I’ll do my best to help you puzzle through your current situation.

Justin Kemp, proclaiming my love at a scenic overlook on top of a mountain, 2010. Tree carving; video on website 1’30”

First, let’s deal with practical matters. If you really want to attempt a defense that doesn’t sound elitist, you could cite the studies on Facebook and anxiety and what it does to your self-esteem. Or you could try a more pragmatic tack by talking about how fast technology turns over (remember MySpace and Friendster?), something that the techno-pundits are already discussing. You could mention that Facebook’s IPO was miserable compared to financial projections, the site is losing users, and co-founder Dustin Moskovitz and board member Peter Thiel are dumping millions of shares of stock from their portfolios—not a good sign. And in case you thought FB was the only villain, Twitter is now going to be spamming everyone’s feed with “promoted tweets” based on their interests. Because nothing in this world is truly free, all social media moves in the direction of targeted advertising, which they accomplish by tracking your data.

But really what you need to do, instead of mounting an airtight defense, is to stop comparing yourself to your friend—and stop letting him compare his situation to yours, because they’re completely different. He has a vested interest in being a part of social media: as a radio-show host, he’s a public figure with a specific message. Radio stations are supported by advertising, which the radio station sells to businesses by telling them how many people will hear their ads. They can increase that number of listeners, and then sell ads for more money, by using social media to market the show. By tweeting his political views or NOM NOM sushi lunch, your friend could be ultimately ensuring that he has a job next month. (Just as I’m sure that my editors are reading this right now and thinking, Yes, darling, get a damned Twitter account already and help us sell some advertising so we can keep on cutting checks for this column. But I digress.)

Justin Kemp, surfing with the sand between my toes (after brian wilson), 2010. Sandbox, Mac Pro, desk and chair in living room

Of course, you are an e-prude, at least by today’s standards. If that makes you feel insufferably bad, you’re either going to have to give it up and get publicly naked on the internet or else cultivate a sense of pride and learn to wear your smug, elitist, aloof moral superiority (because that’s certainly what you’ll be accused of) as a badge of honor. If you opt for the latter, recognize now that you may never get to have a normal conversation about the Internet again. No matter how neutrally you frame it, some people will look upon your lack of social media presence as a negative assessment of their own habits and get defensive and preachy. I spent ten years without a television, and learning that fact never stopped anyone from first heartily vowing that they never really watched TV either, and then following that up by recounting the plot of some idiotic sitcom that they were convinced I would just adore. I expect it’ll be the same with social media—your obvious expression of disinterest won’t make the proselytizers go away, so if you hold your ground just resign yourself to having that chat. But you’re a creative person, right? So surely you can figure out a creative way to get people looking at your work without compromising what you believe in.

Read More »