Help Desk

Help Desk: Participatory Project

Help Desk is an arts-advice column that demystifies practices for artists, writers, curators, collectors, patrons, and the general public. Submit your questions anonymously here. All submissions become the property of Daily Serving.

I’m an artist working with a poor family on a participatory project at a local museum. They are Latino. The project is about their perceptions of art. Who might I talk to or where might I look for similar projects, or even guidance on working with this population? I’m not Latino or poor (or low-income, opinions vary widely on terminology).

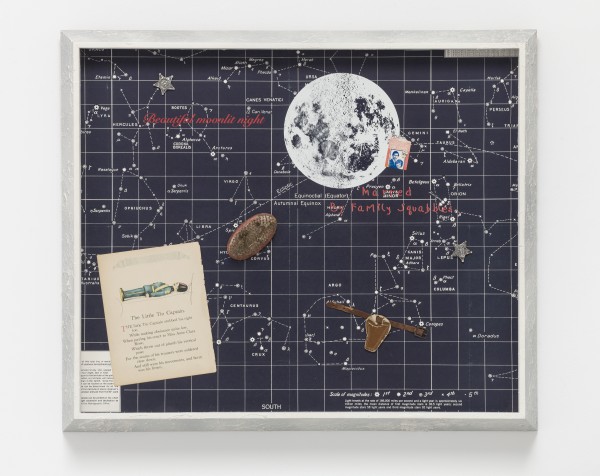

Joav BarEl. Center of the World, 2014; installation view, Tempo Rubato Gallery, Tel Aviv.

The Thanksgiving holiday is just behind us, but I want to begin by stating my sincere appreciation for this question, because it supplied me with the opportunity to contact some of the most generous people in the Western Hemisphere. Given the events of the last few weeks, the following warm and thoughtful responses are especially welcome right now, and it’s the right time (is there ever a wrong time?) to be talking about socially aware art projects and communication between groups of people.

Because of his extensive practice and his knowledge of working within institutions, it seemed only right to reach out to Pablo Helguera first. This is his response:

“I think this artist would be best served by working with the education department of that museum—usually people in the education department are professionally trained to work with various groups of people, and regularly do outreach and other programs that involve them in a conversation about art. But first the artist perhaps needs to define the goals for this project, and exactly the kind of participation he/she is aspiring to get. Second, if the project is about [the family’s] perceptions of art, there are an infinite amount of programs that involve communities in that. The artist would need to determine why or how this is not an education program versus a socially engaged art project (i.e., Is the family going to learn something about the museum, or is this artist going to work with them to develop a new project?). Depending on what this artist is hoping to achieve, there are many successful programs at other museums that may be of interest, such as SFMOMA, Queens Museum, etc. Not being ‘Latino or poor,’ as this artist says, should not be a limitation if one is working as a professional in the field. It is more about the recognition of difference and how this is communicated that matters.”