Help Desk

Help Desk: Interviews & Expectations

Help Desk is an arts-advice column that demystifies practices for artists, writers, curators, collectors, patrons, and the general public. Submit your questions anonymously here. All submissions become the property of Daily Serving.

I have an interview with a critic who sent me his questions in advance, and I found them to be leading and directive. How can I approach this type of conversation in a way where I can communicate what I feel is interesting about my work? For many artists, dealing with writers and art reviewers is an inevitable part of showing work. What are some tactics in general for making these conversations go well, for both interviewer and interviewee?

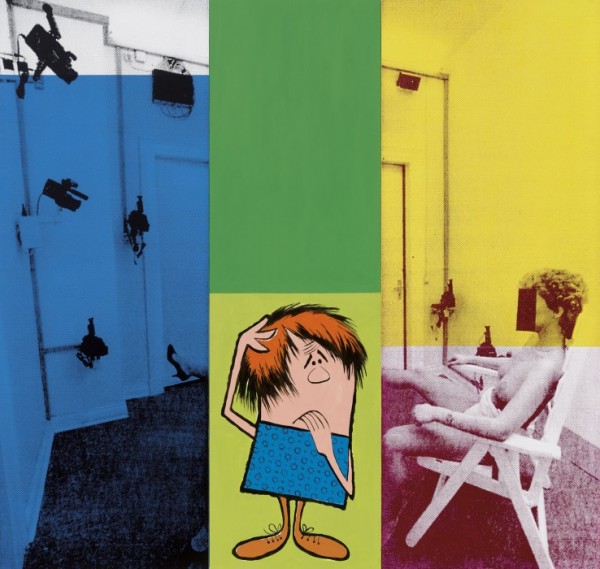

Julia Wachtel. Bleep, 2014; oil, flashe, acrylic ink on canvas; 60 x 73 in. Photo: David Brichford

Interviews can be tough even when the interviewer is sympathetic and savvy. Beyond the questions, so many other considerations are at play—including various hierarchies and a hunger to please your audience—that it can be difficult to think clearly enough to describe your own process. On top of that, if you feel the interviewer has an agenda that doesn’t match your own, the experience is potentially quite uncomfortable. But take heart, there are some strategies that you can use to boost your confidence and make the conversation more pleasant.

First, the basics: Research the journalist’s prior interviews and find out where yours will be published. Be aware that it will almost certainly be tailored for a specific audience (think Artforum versus a local newspaper), and even if you don’t wish to modify your answers for a particular readership, bear in mind that the conversation will be edited before publication. If you’re meeting in person, bring your laptop or iThing pre-loaded to your website—you might answer a question by discussing a piece that the interviewer hasn’t seen before, and images will aid you. Remember to take a slow, deep breath before you reply—and don’t worry how that might appear in the moment, because it’s the final publication that counts and in print no one hears you pause. Keep your answers concise and to the point.