Buenos Aires

Más Allá del Sonido [Beyond the Sound] at MUNTREF

Built in Buenos Aires during the first decade of the 20th century and active until 1952, the Hotel de Inmigrantes (Immigrants’ Hotel) was an immigrant checkpoint and a temporary shelter for exiles and expatriates from overseas. Today, the historic building fosters the National Direction of Migration and the Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero Museum, Centro de Arte Contemporáneo (MUNTREF). Within the building’s aseptic white tiled walls, ample hallways, and long corridors reverberate the sounds from the current exhibition, Más Allá del Sonido [Beyond the Sound]. Including five installations by six artists of different nationalities—Edgardo Rudnitzky (Argentina–Germany), María Negroni and Pablo Marín (Argentina), Eddie Ladoire (France), Steve Roden (USA), and Tintin Wulia (Indonesia)—guest curator Anne-Laure Chamboissier’s vision defies the exhibition space’s prototypical use as a container, and instead turns the building into an essential component of the pieces’ making. With each step taken through the exhibition, the symbolic weight of the venue’s history builds a dialogue with the works and visitors as a way to reinterpret paths and wanderings. From images to texts, to sounds and movements, migration becomes a strong leitmotif, not only in its historical dimension, but also as a perceptive experience.

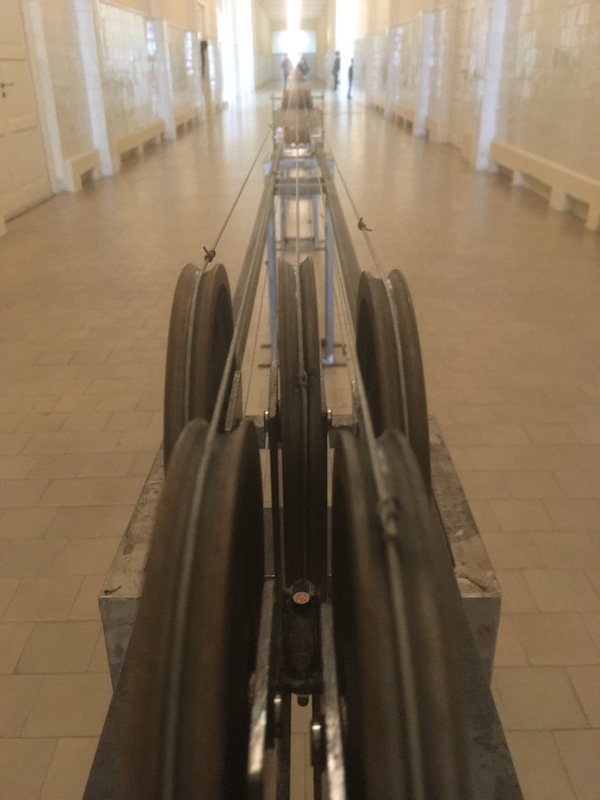

Edgardo Rudnitzky. Border Music, 2016; steel, iron, barbed wire (custom made), 4 melodikons, wooden resonators, bronze, motor; 78.7 x 5.9 in. Courtesy of MUNTREF. Photo: Tania Puente.

Participating artist Edgardo Rudnitzky has said that “sound is never a private thing; in natural terms, sound is always a public matter. We cannot avoid it. One can actively suspend the understanding, but not the faculty of listening to something.”[1] In this sense, his installation Border Music speaks powerfully to the politics of migration and the experience of crossing the border. Border Music is made of a 20-meter rotary machine powered by an engine. Five lines of barbed wire are sent from one side of the machine to the other. The barbs emulate music notes on a staff, and the wires traverse various sound checkpoints where contact with four melodikons and wooden resonators create fragile bell sounds. Within the piece’s intimidating steel frame, the subtle, submerged melody lulls listeners into an ambient contemplation that demands attention to the many tragedies caused by fences and walls that separate nations and communities. The physical divide of space that Border Music creates may be real, but the sounds it emits have no parameters, and will not remain silent.

Edgardo Rudnitzky. Border Music, 2016; steel, iron, barbed wire (custom made), 4 melodikons, wooden resonators, bronze, motor; 78.7 x 5.9 in. Courtesy of MUNTREF. Photo: Tania Puente.

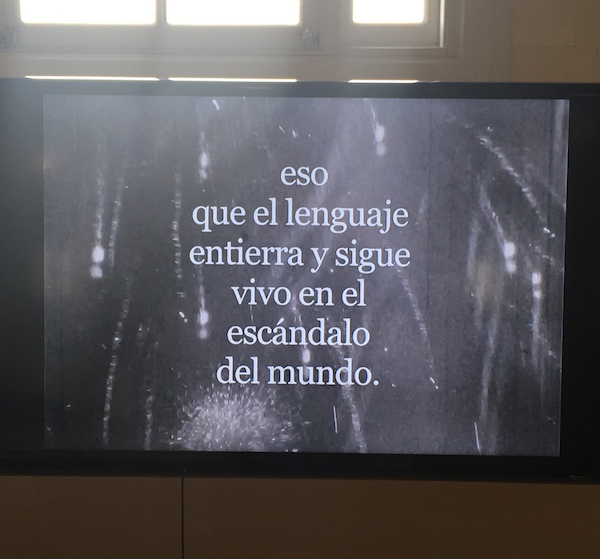

Through the hallway where Border Music is located and into the middle of the main room, which is surrounded by large windows that offer views of the river, is the video installation Angelus Novus. Poet María Negroni and filmmaker Pablo Marín present a two-minute, forty-nine-second video that alternates between visual reels and sound loops excerpted from Negroni’s poem “Exilium.” Walter Benjamin’s studies on Paul Klee’s drawing Angelus Novus are a clear reference for this piece; both address terms of catastrophe and the ruins of history. In the video, Negroni’s sampled voice is repetitive but never quite completes the full loop. The correspondence between her audible declamation and the written text displayed onscreen is never achieved. The text is accompanied by found footage and homemade videotapes that give the viewer the sense that they are entering into a very intimately selected archive of what is lost and found in exile. Although the experience of exile eludes being portrayed in an audiovisual, albeit poetic piece, the medium resonates strongly and impregnates its narrative with empathy and melancholy.

María Negroni and Pablo Marín. Angelus Novus, 2016; two-channel video installation, variable length, color, sound; loop. Courtesy of MUNTREF. Photo: Tania Puente.

Tintin Wulia’s sound installation Babel makes us wonder: Is an immigrant shelter a tower of Babel on its own? In a place where people from different parts of the world, and in considerably vulnerable states, gather in search of assistance, is there a possibility for cultural exchange and a will to understand? Located by one of the building’s two staircases, sixteen speakers play a variety of unintelligible spoken recordings simultaneously. While it is possible for a singular speaker to broadcast each reproduced testimony clearly, the cacophony of all sixteen projecting at once make the messages incomprehensible. What happens to the experience of otherness when all hierarchy is diffused? Can it be grasped? Does it exist? In between speakers and steps on the staircase, the artist has placed small linen pillows that materially invite visitors to stop and listen; with this gesture, Wulia demarcates a space for consciousness, one that demands concentration and compassion.

Tintin Wulia. Babel, 2013; 16-channel synchronized sound installation; 11:45. Courtesy of MUNTREF. Photo: Tania Puente.

Steve Roden’s pieces find a correlation with this question. In his videos, Lines and Faces (2014) and Disorder (2016), audio is barely perceptible, forcing spectators to focus and challenge their preconceived expectations while watching actions that are most often accompanied by loud sounds, such as tearing sheets of paper. Also on display is a series of drawings and collages on sheet music titled Water Music (Drumming), and a series of serigraphs titled Cascade (made in collaboration with Leandro Jacob) that utilizes song lyrics about the rain in different languages. Everything in Roden’s installation speaks about sound, but the artist denies visitors the opportunity of ever listening to it. The room incubates an anxious, outsider feeling.

Exhibition view with art installations by Steve Roden. Courtesy of MUNTREF. Photo: Tres Consultores.

As its title accurately states, Beyond the Sound not only takes the sense of hearing into visuality, literature, and movement, but expands its vehicle to the museum and its history. MUNTREF doesn’t operate merely as a venue for this exhibition—it has an essential role to play in completing the pieces conceptually. The building’s architecture and its various uses throughout history, together with the works installed, craft a sonic palimpsest that holds as many stories as the layers that comprise it.

Más Allá del Sonido will be on view through December 30, 2016.

[1] Spoken at the conference “En los Bordes de lo Real,” 10º Meeting Sur Global, MUNTREF, September 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d26r7mtko9k&feature=youtu.be.