Columbia

Remix at the Columbia Museum of Art

The recent curatorial trend of probing the fringes of art history for artists who have been eclipsed by the canon of white, European, male artists is a noteworthy one. While shows that feature such artists—in many cases, those who are Black—are becoming more prevalent, organizers must take care to contextualize the work without reinforcing myths that persist. The curators of Remix: Themes and Variations in African-American Art at the Columbia Museum of Art achieve this with their exhibition. Featuring a diverse group of artists and meticulous contextualization, this show helps to elucidate the creativity and motivations of African American art from the past several decades.

Fahamu Pecou. Rock.Well (Radiant Pop, Champ) (After Norman Rockwell’s Triple Self Portrait), 2010; acrylic on canvas; 48 x 48 in. Courtesy of Scott and Teddi Dolph and Columbia Museum of Art, South Carolina.

Taking the concept of the remix as a theme, the show features forty artists who recontextualize familiar visual forms in their own works. Several works interpret famous pieces from art history and popular culture. As such, the show exemplifies a dialectic model in which the works are synthesized through the artists’ engagements with art history. Instead of focusing on collage and digital media—two formats closely aligned with the concept of the remix—the curators also present works in more traditional media, such as painting and drawing, that evince the diversity of creativity.

In the exhibition, the artworks that plainly cite famous predecessors introduce the idea of the remix. One of the first such works encountered is Fahamu Pecou’s Rock.Well (Radiant, Pop, Champ) (After Norman Rockwell’s Triple Self Portrait) (2010). Pecou’s version of the popular painting replaces Rockwell’s artistic influences (Dürer, Rembrandt, Picasso, and van Gogh) with his own: Muhammad Ali, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Andy Warhol. Bob Thompson’s Bathers (1964) is a scintillating amalgamation of similar erotic scenes painted by Europeans such as Paul Cézanne and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres; Thompson’s insertion of Black bodies into the picture reminds the viewer of the exploitive, exoticist paintings of the late 18th century. Similarly, Robert Colescott’s brilliant and sardonic Between Two Worlds (1992) blurs racial boundaries by portraying the figure in Diego Velazquez’s famed Toilet of Venus (1647, known as “the Rokeby Venus”) as a Black woman with a White reflection; her palpable angst in this scenario anticipates the country’s current inability to reconcile racial differences more than two decades later.

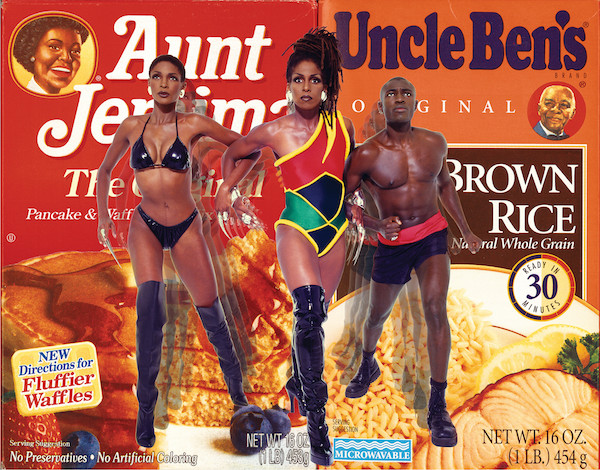

Renee Cox. Liberation of Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben, 1998; dye destruction print, mounted on Diasec; 48 ½ x 61 ½ in. Courtesy of the Artist and Columbia Museum of Art, South Carolina.

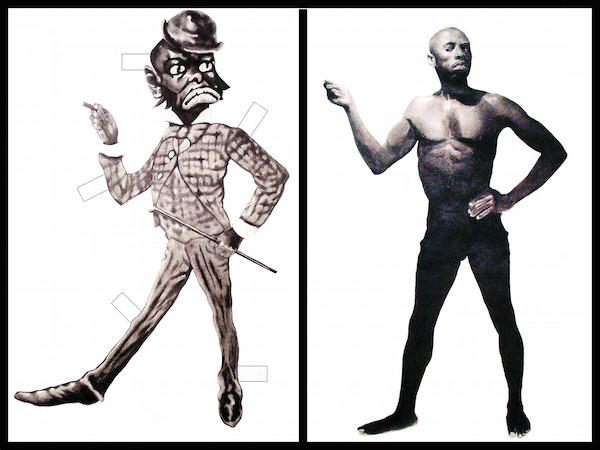

A number of artists use pop-culture references within their work, and the majority of such works specifically engage the facets of the dominant culture that marginalize and caricature Black bodies. Damond Howard’s Untitled Diptych from his Wearing the Mask series (2007) features two large charcoal drawings that juxtapose his own body with a blackface caricature. The artist’s pose mimics that of the inflammatory cartoon, but his performance of it forcefully establishes his own identity as a Black man. Krista Franklin riffs on the infamous album cover of the Ohio Players’ 1975 release Honey, which features a nude woman seductively consuming the eponymous substance. Whereas the original image presents the woman as an object of desire, Franklin’s collage Oshun as Ohio Player(s) (2013) extrapolates from the album cover, portraying the woman as the Yoruba goddess Oshun. Iona Rozeal Brown’s A3 Blackface #65 (2003) is reminiscent of a Japanese woodblock print of a female entertainer: The woman in blackface presents a stark contrast to the typically white makeup of a geisha.

Damond Howard. Untitled Diptych from Wearing the Mask series, 2007; charcoal on paper; each 84 x 57 in. Courtesy of the Artist and Columbia Museum of Art, South Carolina.

In the exhibition’s final gallery is a juxtaposition that encapsulates the central conceit of the show. On one wall stands a massive work by Mickalene Thomas, Three Graces: Les Trois Femmes Noires (2011). Using vivid colors and rhinestones, Thomas’s rendition updates the classical trio of nude figures as a monumental portrait of three powerful black women. Opposite this work is Tarleton Blackwell’s Hog Series CCX: Las Meninas (Diptych) (1999), an imaginative version of Velazquez’s 1656 masterpiece. Replacing the Spanish royal family with his own family—and several hogs—in this exuberant painting, Blackwell positions himself as Velazquez, collapsing the divide between one of Spain’s most famous painters and a contemporary artist living in a small town in South Carolina. Blackwell’s expressive, painterly style and jocular humor contrast with the power and grace of Thomas’ painting, yet both works synthesize facets of the art-historical canon with the artists’ experiences as African Americans in Western culture.

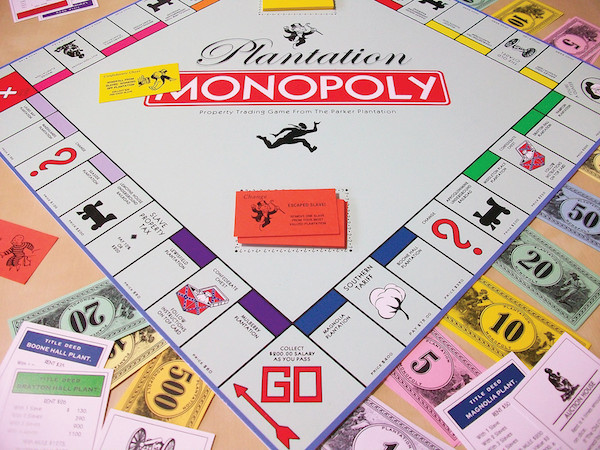

Colin Quashie. Plantation Monopoly, 2012; mixed media; 20 x 20 in. Courtesy of the Artist and Columbia Museum of Art, South Carolina.

With a multitude of works on display, the exhibition presents the results of this dialectical model. In an essay for the catalog, the independent curator Jonell Logan emphasizes that “the artists participating in the exhibition are not borrowing from western culture; they are of western culture [sic].”[1] This distinction is crucial to understanding the work of artists who have historically lacked access to mainstream institutions. The nuance elucidated by this show will help as curators continue to erode the barriers and mythologies that persist in a global art world.

Remix: Themes and Variations in African-American Art is on view at the Columbia Museum of Art through May 3, 2016.