Help Desk

Help Desk: Interviews & Expectations

Help Desk is an arts-advice column that demystifies practices for artists, writers, curators, collectors, patrons, and the general public. Submit your questions anonymously here. All submissions become the property of Daily Serving.

I have an interview with a critic who sent me his questions in advance, and I found them to be leading and directive. How can I approach this type of conversation in a way where I can communicate what I feel is interesting about my work? For many artists, dealing with writers and art reviewers is an inevitable part of showing work. What are some tactics in general for making these conversations go well, for both interviewer and interviewee?

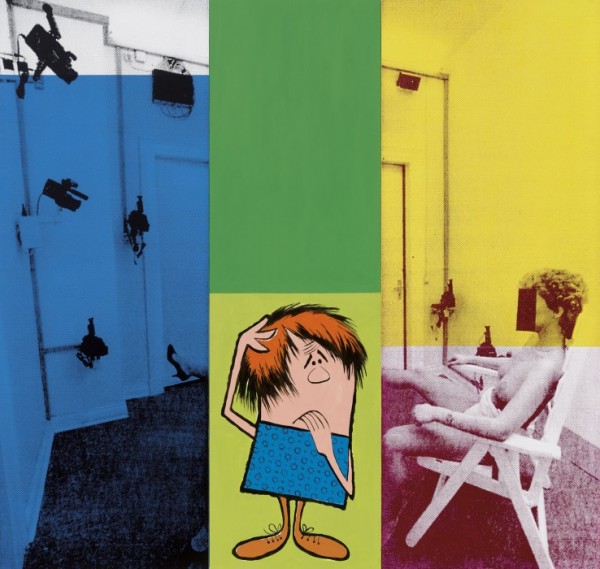

Julia Wachtel. Bleep, 2014; oil, flashe, acrylic ink on canvas; 60 x 73 in. Photo: David Brichford

Interviews can be tough even when the interviewer is sympathetic and savvy. Beyond the questions, so many other considerations are at play—including various hierarchies and a hunger to please your audience—that it can be difficult to think clearly enough to describe your own process. On top of that, if you feel the interviewer has an agenda that doesn’t match your own, the experience is potentially quite uncomfortable. But take heart, there are some strategies that you can use to boost your confidence and make the conversation more pleasant.

First, the basics: Research the journalist’s prior interviews and find out where yours will be published. Be aware that it will almost certainly be tailored for a specific audience (think Artforum versus a local newspaper), and even if you don’t wish to modify your answers for a particular readership, bear in mind that the conversation will be edited before publication. If you’re meeting in person, bring your laptop or iThing pre-loaded to your website—you might answer a question by discussing a piece that the interviewer hasn’t seen before, and images will aid you. Remember to take a slow, deep breath before you reply—and don’t worry how that might appear in the moment, because it’s the final publication that counts and in print no one hears you pause. Keep your answers concise and to the point.

But since you’ve already seen this interviewer’s questions and find them to be “leading and directive,” you’re going to have to be somewhat more Machiavellian than you ordinarily might. Remember former President George W. Bush? Journalists would ask him questions, and he would reply in a way that pushed his own agenda forward, even if it meant that the answer didn’t match the query. Here’s an example from a 2006 interview with Bill O’Reilly:

O’Reilly: Do you think Hillary Clinton is soft on terrorism?

Bush: I think—first of all it’s very important for me never to, you know, question anybody’s patriotism. I believe there’s a group of people here in Washington, however, who have a different view of this war. They view it as a law enforcement matter.

Notice how the question elicits a yes-or-no answer, but G.W.B. sidesteps it entirely, using it instead as an opportunity to introduce the notion of patriotism. If the Bush White House gave us anything (aside from bad governance and a forever war), it was an eight-year master class in evasive tactics. His administration was also expert at staying on message; in the same interview, Bush answers three successive questions with, “We don’t talk about techniques,” “I don’t want to talk about techniques,” and, “Well, one thing is that you can rest assured we’re not going to talk about the techniques we use in a public forum.”

Consider how the interview might serve your career and practice. When you take that little pause before replying, think about whether you can answer part of the question in a way that tells your story advantageously. To be clear, I’m not advocating for anyone to be evil, manipulative, or cynical, but if an interviewer has a set of assumptions that don’t serve the understanding of the work, then the artist should try to correct—though not necessarily control—the message. If you’re doing a phone interview, you could even print out a cheat sheet with some key points that you want to communicate.

Interviews are sometimes intimidating, and even when they are fun, they are demanding. We want journalists to ask just the right questions that will allow us to present the best parts of our work and practices, highlight how articulate and brilliant we are, and make us look interesting and cool. But if that’s not happening, don’t be combative. Instead, focus on damage control: you can ask the critic how he/she sees your work, and then you’re free to respond with, “That’s interesting, because I’ve never considered that—I see my work as…” or some such. If the interviewer uses a particular description to ask about a piece and you don’t agree with the characterization, you can say, “I don’t really think about it like that. For me, it’s more about…” Feel free to contradict the interviewer—gently, politely—because in the end it makes for a more lively read; also, if this is going on the Internet then it will be up forever, so don’t hesitate to represent your work and practice as you see fit. Good luck!