Haverford

The Female Gaze at the Atrium Gallery at Haverford College

The Atrium Gallery at Haverford College is a smaller venue than the works of Diane Arbus and Carrie Mae Weems have seen in the past year; their works have appeared in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, respectively. Yet here they are in the periphery of Philadelphia, along with the likes of Nan Goldin, Vivian Maier, and Tacita Dean, in the exhibition The Female Gaze: A Survey of Photographs by Women from the 19th to 21st Centuries.

Carrie Mae Weems. Untitled (Woman and Daughter with Make-Up), 1990; silver gelatin print, black and white; 10.24 x 10.24 in. Courtesy of Haverford College, Haverford PA.

Centered on the premise of female photography from the past 150 years, the show yields an interesting spectrum of established, canonical artists aside mid-career artists such as Rachel Papo and Jessica Todd Harper as well as those known better for photojournalism, like Sue Sojourner-Lorenzi. The question figuratively hanging in the brightly lit atrium is: What does it mean for a woman to look at something, and to record her observations? Does she impart her supposed womanliness onto said views, and if so, how would we know? Given the historicity of the exhibition, it’s impossible not to imagine the constraints women photographers faced, as well the freedom a lens might grant.

There is a raw intimacy prevalent in the selected works, which is played up through their close vicinity in the salon-style installation. To the left of the entrance is perhaps the boldest section—though the individual works are modest in scale—which leads with Arbus’ Albino Sword Swallower at a Carnival (1970). The grayscale silver gelatin print depicts a woman of indeterminate age, in layers of richly textured clothing, arms spread Jesus-style with half an ornate sword down her throat. With a backdrop of a dark, billowing tent, one can imagine the performed act as a personal favor to Arbus, part-braggadacio, part-trust fall; a secret exchange behind the carnival scenery.

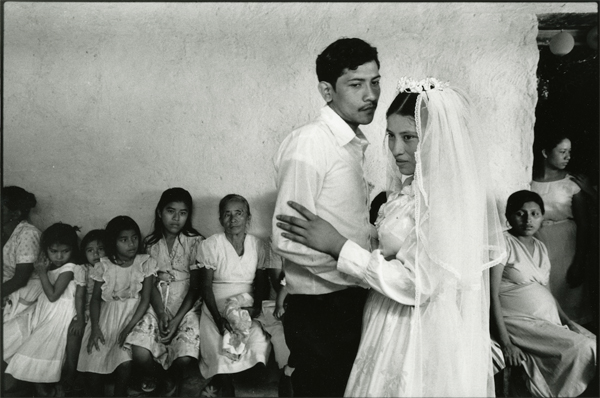

Susan Meiselas. Wedding, El Salvador, 1983; silver gelatin print; 11.9

by 17.7 in. Courtesy of Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

The walls are crowded, which imparts an odd hierarchy of vision in which the most sensational works (the Sword Swallower’s Christ-on-the-cross pose), as well as the extremely reticent in subject matter, jump out of the mostly black-and-white collection. One piece that fulfills both extremes is Sailor and Girl (1940) by the inimitable Lisette Model. Here, Model has caught the breath before romantic intimacy, the girl demure, with eyes downcast and a smile playing at the edge of her lips; a flower in her coiffed hair and eyebrows drawn on like razors heighten the mid-century glamour. The sailor moves in, eyebrows furrowed and mouth slightly parted. How Model got in this close with a camera is astonishing—the distance was probably only about two feet, the girl’s cigarette foregrounded as to almost break the frame. The curious part is the role Model must have played in the social scene: immersed but with arms raised, eyes open, catching the heart that shines through the sly debauchery of her subject matter.

In the far corner of the space are Susan Meiselas’ Wedding, El Salvador (1983) and Helen Levitt’s Mother and Child, N.Y.C. (c. 1930). As with many of the works here, the subject matter is domestic—even ritualistic. Susan Meiselas, a Magnum documentary photographer and MacArthur fellow, presents the first dance of a newly married couple, the bride bedecked in white lace and the groom having the air of someone who hates to dance. A row of bored children slump against an older woman behind the couple, while to their right a very pregnant guest sits staring at them, foreshadowing their next step in life. But at this moment in time, the bride and groom stare off in opposite directions, waiting for the spotlight to dim. This scene is a small familial respite in Meiselas’ politically charged series El Salvador. Training of Atlacati Battalion hangs above Helen Levitt’s urban mise-en-scène of an African American mother in a housedress gesturing to her child, old enough to be walking but young enough to unspecified in gender, on the steamy concrete of New York City streets. These two black-and-white silver gelatin prints, both only eleven by thirteen inches, seem intrusive yet welcoming. A wedding is public presentation of an ostensibly private decision, while the intimacy of mother and child plays out on the stage of a city sidewalk. These photographs function as traces of an undoubtedly subjective, even implicit, witness.

Helen Levitt. Mother and Child, N.Y.C., c. 1930; gelatin silver print, black-and-white; 11 x 13.8 in. Courtesy of Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

All of this historicizing demands a look forward, provided in one of the (oddly unnecessary) vitrines of the exhibition. Deana Lawson’s Coulson Family (2008) is small—seven-and-one-half by ten inches—but the questions of composure and assembled identity it raises makes it seem more expansive. An African American mother sits with crossed ankles between her two young sons. In stiffly pressed Sunday best, they pose dutifully for the camera; the younger boy smiles adorably with his hands behind his back. Behind is a cobalt-blue faux Christmas tree, adorned with gold and white tinsel, and the walls of the living room rise up in a cerulean wash. Stacks of DVDs in the entertainment center to their left support a mantle of wood-framed photographs, angled jauntily. The image is both familiar and posed. Deana Lawson, one of the youngest artists in the exhibition, is known for her visual exploration of black culture, of what it means to take on an identity and perform it, of what performativity means in larger social systems.

The other “women photographers” here are also performing roles. In this exhibition, the position of the photographer is also constructed: She is an inside outsider, and the subject as well as the image maker; she explores the duplicitous nature of the photograph itself, a representation of a moment irretrievably gone and a promise of new modes of perception to come. As illuminating as this exhibition is, I look forward the end of these gender-specific shows—when we can just say photographers, and artists, as sex disappears from its supposed role as a pre-determinant of subject and style.

The Female Gaze: A Survey of Photographs by Women from the 19th to 21st Centuries is on view at the Atrium Gallery at Haverford College through November 30, 2014.