San Francisco

Women in Performance: Rigorous Ecstasy – Language & Performance, Part I

Today from our friends at Art Practical, we bring you the first installment of the new column “Women in Performance,” which kicks off with an interview between author Jarrett Earnest and artist Carolee Schneemann. To quote from the column’s introduction: “Impelled by painting, Schneemann has plumbed the history of images, embodiment, and language since the 1950s, creating pioneering performances, films, installations, sculptures, and drawings. This two-part interview focuses on her relationship with writing, drawing, teaching, and the evolving nature of performance today.” This part of the interview was originally published on September 15, 2013.

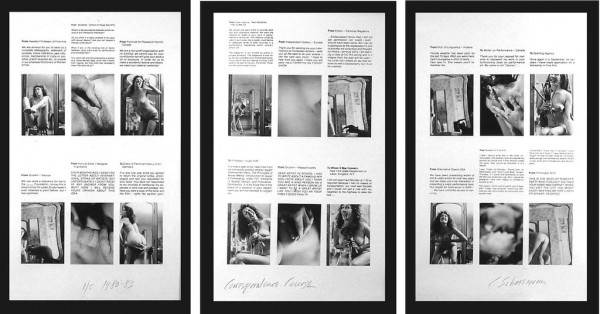

Carolee Schneemann. Correspondence Course (triptych), 1980/1983; self-shot silver prints mounted on silk-screened text; 30 x 20 in. Courtesy of the Artist and PPOW Gallery, New York. © Carolee Schneemann.

Jarrett Earnest: One thing that has been important for the deeper understanding of your work has been the publication of your letters and writing. When did you start writing, and how do you see it in relation to your visual art?

Carolee Schneemann: I wish I could grasp the writing. When I write, I cannot remember what I wrote. Writing is so difficult; it’s like a terrible kind of sculpture. But I was writing from the time I was a kid. I had Bruderhof neighbors who had a little printing press, and one year for Christmas, they printed a book of my poems—probably about cats, water, and birds. I was nine or ten. In school I was always writing; when I had a good teacher, they were respectful of it.

JE: The great thing about the publication of your letters is that it shows how important fiery missives are as part of your work: “This is not how you talk about my work. That is not what I was doing.” You are allowing people to have their own ideas; you are just insisting that they properly understand what’s actually going on. That means getting the words right.

CS: It is especially difficult the more these enclosing terminologies establish themselves as irrefutable. You can’t even talk about what you do unless you go through this nightmare of linguistic intervention. I’m doing a lot of writing now about these deformations of language—for instance, references to studio process as “practice.” I wrote an enraged letter once saying: “Dentists have to practice. Ballerinas practice. Visionary artists do not practice! We enable. We enact. We realize.” Also, we do not have ‘careers.’ What language-devils have evolved to substitute “unpacking” for “research”? I have a whole list of hateful language problems. I received a beautiful but bewildering essay this week from an English graduate student comparing Woolf’s The Waves and my Fuses (1965). It kept referring to the “film plate.” What? The sausage and eggs on a plate? It uses this expression over and over. I didn’t know what it was, so I wrote to her: “You are in the same coven—the moldering den of academics—destroying our ability to think straight with these deformed expressions!” I was very harsh, and she wrote back and said: “I’m only 22, and I’m at Oxford, and I don’t have anyone with imagination here, but I believe I’m a good thinker.” Bless her heart! She’s a very good thinker, and I can’t wait to meet her.