New York

Here and Elsewhere at the New Museum

Here and Elsewhere, the New Museum’s colossal survey of contemporary art from the Arab world, sets for itself an impossible task. The curatorial strategy, as stated in the exhibition’s press release, is to work “against the notion of the Arab world as a homogenous or cohesive entity.” Though able to present a range of Arab identities, regionalisms, and geographies, the sprawling installation self-organizes and familiar tropes begin to emerge. As every archetype is anchored in a truth, the images of war-torn streets, monuments to fallen dictators, dusty Bedouins in desert landscapes, and gleaming symbols of oil-soaked capitalism here are resonant and believable. Even so, the choice to include forty-five artists and collectives renders the exhibition both overwhelming and incoherent, and the huge number of works strains the already limited functionality of the museum’s signature building.

Rather than impose some significant through-line on the cacophony of voices that make up Here and Elsewhere, despite the curators having opted not to, I will instead focus on a few key works that offer surprising and provocative views of the contemporary Arab experience, while indicating some omissions in our understanding of who is present in the “Arab world.” From the start, the exhibition positions Arab identity as closely connected with post-colonial struggle, from Lebanon to Palestine to Egypt. On the museum’s fifth floor, Ala Younis has curated an exhibition-within-an-exhibition titled An Index of Tensional and Unintentional Love of Land, consisting of contemporary artworks and compelling excerpts from photojournalistic archives in the United States and around the Middle East. This installation provides a framework through which to view the whole of Here and Elsewhere, prefiguring the historically reflexive or even speculative approaches offered by many of the artists on the lower four floors.

In one particularly compelling display case within Younis’ installation, heroes of resistance movements past proliferate in archival photographs, magazine spreads, propaganda films, and official postcards, demonstrating how the Pan-Arabism of mid-century post-colonial liberation movements has sustained a sense of contemporary Arab selfhood as forged in resistance and struggle that persists to this day. Leaders like Gamel Abdel Nasser, the Egyptian president who helped to build a sense of Arab political unity in the 1950s and ‘60s, and the leaders of the PLO in the 1970s reinforced a sense of Arab nationalism as revolutionary militancy against the ongoing Western imperatives of exploitation that have borne heavily on the region for well over a century. Nasser’s socialist/nationalist/modernist promises and those of his successor Anwar Sadat were quite possibly based on an unsustainable basis of economic protectionism and militarism, and their legacies would devolve into turgid corruption and merciless violence under regional leaders such as Hosni Mubarak, Muammar Qaddafi, and Bashar al-Assad. Yet, they may appear attractive to a younger generation precisely because their collectivist dreams were so short-lived. Palestinian leadership, especially the PLO, is idealized in archival photographs showing Palestinian children and teens performing military drills. What these materials make clearest of all is how the construct of pan-Arabism depends on military opposition to Western powers and their Mideast proxy, Israel, to foster a sense of commonality among the largely dissimilar communities who make up “the Arab world.”

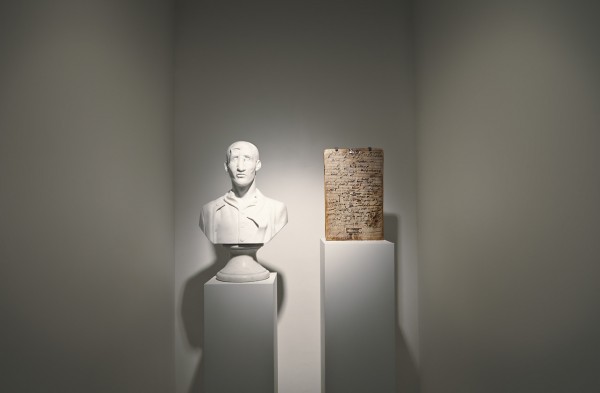

Kader Attia. Repair, Culture’s Agency, 2014; Courtesy New Museum, New York. Photo by Benoit Pailley.

Though I tend to favor intergenerational discourse in contemporary exhibitions as a rule, in the case of Here and Elsewhere the broad range in age across the many artists represented can at times result in a fractured sensibility due to significant differences in artistic styles and discursive frameworks. Artists born in the first half of the 20th century, like Etel Adnan and Anna Boghiguian, display an ethos akin to that of Negritude-affiliated artists in Senegal or the Bombay Progressive Group in India—modernists forged in a nationalist crucible as a cultural counterpoint to economic policies supporting local manufacturing and agriculture. This mode of working positions Pan-Arabism as self-sufficiency, described through a Western-imported formal language run through with culturally specific symbols and motifs. Younger artists make work shaped by the values of the global biennial/art fair circuit: photography, short-form video, assemblage, appropriation art, process art. More importantly, senior artists seem at ease in the slipstreams of globalization while younger ones—even, or especially, those born in the US and Europe—tend to problematize mobility of this kind.

Bouchra Khalili. The Mapping Journey Project, 2008–11; Courtesy New Museum, New York. Photo by Benoit Pailley.

Among the latter group, Kader Attia and Bouchra Khalili offer cogent examples of this mistrust of global trajectories, experienced from within. Attia is among the most prominent artists of this generation, having exhibited a large body of work in the last Documenta that relates to the small works presented here. His interest is in the damage and repair done to bodies and to knowledge at the end of the Imperialist era ushered in by World War I. At the New Museum, Attia pairs a bust of a French soldier bearing sutured facial injuries sustained fighting in North Africa with a child’s wooden school tablet, split in two and reattached. Khalili addresses damages in a different way, chronicling the impact of transnational borders on the lives of migrants who have traversed them out of economic or personal necessity. In a multi-channel video installation, the interview subjects draw their trajectories on paper maps, revealing only their hands and their tales to viewers. A South Asian man describes transiting through construction jobs in the Middle East, only to land in Italy seeking refuge from labor abuses. A Palestinian man details the half-day of travails he experiences each time he goes to visit his girlfriend in Jerusalem, just a few short miles away. Here again, we see how global conflicts and imperialist agendas fracture the lives of individuals. Meanwhile, Khalili’s work also makes visible those denizens of the “Arab world” who cannot participate in Pan-Arabism, such as the Bangladeshi laborer or the Palestinian in Jerusalem or Ramallah.

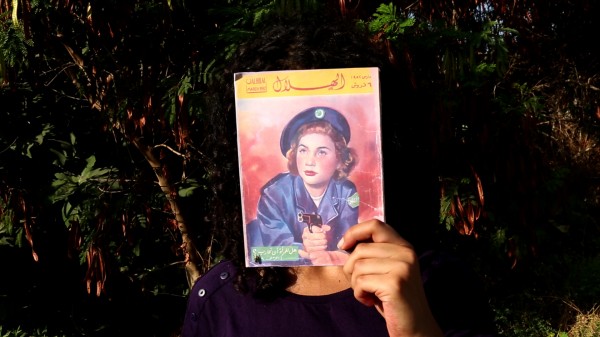

Consider again the alternative to this rootless, displaced fragmentation: Arab nationalism, anchored in struggle. Marwa Arsanios explores this identification to a chill-inducing degree in “Have You Ever Killed a Bear? Or Becoming Jamila” (2012-13), a film about a film, following the thoughts of an actress cast to play Algerian revolutionary fighter Jamila Bouhired. Arsanios considers Bouhired, who is the subject of several biopics, as a cultural icon and an archetype of femininity linked with the non-traditional work of armed resistance. The young actress’ research and physical emulation of Jamila (represented in film by a wide range of physical types) lead to attempts to mentally “get into character” while out in the public sphere of post-civil war Beirut, creating a tension between the militaristic zeal of the would-be café-bomber and the cosmopolitan tranquility of the city, always on the brink of instability.

Here and Elsewhere, named for a film by Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville that began as pro-Palestinian propaganda and evolved into a treatise on the shortcomings of representation, is a show caught between political activism and postmodern multiculturalism. The activism is most stirring when the political beliefs reflected do not comfortably align with those of museum visitors. The multiculturalism is most jarring when the opulence of certain regions of the Gulf is juxtaposed with the impoverishment of Palestinian and Syrian refugee camps. Significant regional undercurrents of feminism and organized labor are addressed obliquely, but not overtly, which adds to the sense that Arab identity continues to be dictated by its most powerful adherents. The true test of this show’s value will be whether the many talented artists who are making their US debut here turn up in future shows wherein their Arabness is not a factor.

Here and Elsewhere is on view at the New Museum through September 28, 2014.