Paris

Edgardo Aragón: Mesoamerica – The Hurricane Effect at Jeu de Paume

In 1527, Olas Magnus drew the Carta Marina, the first detailed account of Nordic geography and the perils plaguing it by land and sea. In the image, life seems threatened mainly by ongoing human conflict and a perpetual battle with weather, but what haunted imaginations for centuries was its depiction of the monsters inhabiting the northern seas. Their presence was a documentary mix of fact and fiction—they represented real animals as sighted and interpreted by fishermen, as well as bad omens relating to the political turbulences of their times.

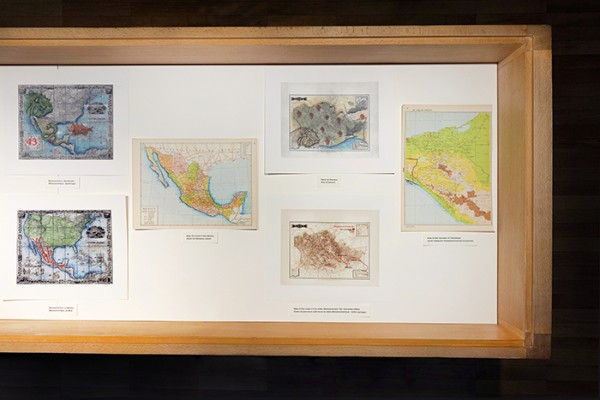

Edgardo Aragón. Mesoamerica: The Hurricane Effect, 2015 (detail of map); HD video, color, sound; 16:20, with 10 maps. Coproduction: Jeu de Paume, Paris, Fondation des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques and CAPC Musée d’Art Contemporain de Bordeaux. Courtesy of the Artist and Jeu de Paume.

Magnus’ monsters take on a new dimension in Mesoamerica: The Hurricane Effect, Edgardo Aragón’s exhibition of maps, a video, and an accompanying publication at Jeu de Paume in Paris. Aragón takes viewers on a journey that starts with an array of ten maps that illustrate the economic and political forces struggling for control of the region comprising Mexico and Central America known as Mesoamerica. Departing from an 1857 map that, as the artist notes in the publication, “interestingly” includes the totality of the region as part of the United States’ territory, we perceive Mesoamerica as a route for the trafficking of people, drugs, and natural resources.

The sea creatures depicted in the maps of yore are used here to represent the main culprits: drug lords, political parties, and mining companies. Although clearly destructive, the beasts in Olas Magnus’ map remain at bay in the vastness of the cold sea, whereas in Aragón’s interpretation they almost cover entire countries, turning them into vulnerable vessels doomed to sink. Three final maps show us Oaxaca, the small town of Cachimbo in the state of Chiapas, and a route traced in red between the two that hints at the trip developing in the single-channel video projected in an adjacent room.

Edgardo Aragón. Mesoamerica: The Hurricane Effect, 2015 (detail of maps); HD video, color, sound; 16:20, with 10 maps. Coproduction: Jeu de Paume, Paris, Fondation des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques and CAPC Musée d’Art Contemporain de Bordeaux. Courtesy of the Artist and Jeu de Paume.

The first image—a wind turbine tower ablaze, its white blades still turning in the air—sets a gloomy, disturbing tone. Viewers follow Aragón on a road trip from Ocotlán to Cachimbo, encountering on the way a hydroelectric plant, a wind park, and their surrounding stories of social injustice. Contemplative shots of a silent, deserted landscape alternate with views of the road and the artist’s smartphone screen, where he shows us maps and hashtag searches relating to local news of industrial accidents. The role of social media in the dissemination of otherwise ignored local scandals echoes the now internationally known murder of forty-three students from the neighboring state of Guerrero in 2014.

The story of Cachimbo resonates throughout the region thanks to policies like the North American Free Trade Agreement signed between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico in 1994, and the Mesoamerica Project, a development plan with dubious long-term goals established in 2008 by then-president Vicente Fox. In line with the reality of these policies, Cachimbo—a town regularly battered by hurricanes—is surrounded by sources of energy and natural wealth, yet the locals have no access to any of it. Aragón’s mission to bring to this town some much-needed electricity, if only in the form of what appears to be a small motorbike battery, is as absurd as it is significant.

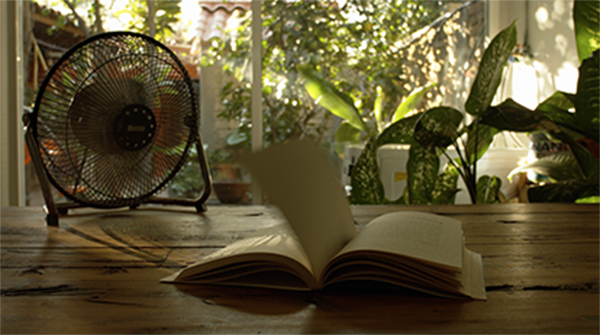

Edgardo Aragón. Mesoamerica: The Hurricane Effect, 2015 (detail of video); HD video, color, sound; 16:20, with 10 maps. Coproduction: Jeu de Paume, Paris, Fondation des Arts Graphiques et Plastiques and CAPC Musée d’Art Contemporain de Bordeaux. Courtesy of the Artist and Jeu de Paume.

The profusion of references employed by the artist may prove challenging for a public who may know only the generalities of the complex and idiosyncratic relations of power and capital in Latin America, yet the artist’s choices seem to be an appeal and an insistence to be read and understood in his own undiluted terms.

Aragón lays out a final, if impossibly thick, layer of meaning in a beautiful last scene in which a fragment of Andrés Henestrosa’s The Men Dispersed by the Dance (1929) is read aloud while a small electric fan whirls, powered by the artist’s battery. Henestrosa’s work is fundamental to the Mexican movement of indigenous narrative, and his prose is used by the artist to point to a conflicting religious syncretism between the ancient Zapotec cosmogony and an imposed Christianity that dictates compliance to adversity, turning tragedy of all kind into an unchallenged part of everyday life.

Contemporary art from Mexico often shows the urgent need of its producers to engage with the social issues in the world around them. As Edgardo Aragón shows in his unapologetic work, these issues are centuries old, scary, and more destructive than any sea monster. Maybe, like Olas Magnus’ creatures, their horrors also precede great social upheaval. Only time will tell.

Mesoamerica: The Hurricane Effect by Edgardo Aragón is on view at Jeu de Paume through May 22, 2016. It will travel to the Musée d’Art Contemporain de Bourdeaux, where it will be on view from September 15 until November 6, 2016.