Dhaka

Five Emerging Artists from Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, the 2016 Samdani Art Award exhibition (one of seven shows that was part of the Dhaka Art Summit) provided a survey of some of the most engaging young artists working there. Daniel Baumann, director of Kunsthalle Zürich, selected thirteen artists from over 300 applicants. In his introduction to the show, Baumann wrote that he had the sense that “something was going on there” when he visited to meet the short-listed artists and curate the final exhibition. Looking at a handful of these artists will elaborate just what that “something” might be.

Zihan Karim and Chang Wan Wee. Habitat, 2013; installation view. Courtesy of the Artist, Dhaka Art Summit, and Samdani Art Foundation. Photo: Jenni Carter.

Even before entering the exhibition gallery, viewers are confronted with a video work by Zahin Karim and Chang Wan Wee on a large flat screen. Habitat (2013) has a Beatles soundtrack, and as viewers listen to the refrains of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band, they watch images of children living in the squatter settlements of Chittagong, Bangladesh’s second-largest city. The project was made in response to the destruction of a previous settlement, which was bulldozed to make room for an airport. A text included in the video explains that the new settlement is on public land that might be developed in the future, so these inhabitants are living with no money and very little security. Bangladesh, the birthplace of microfinance, is a poor country, yet Habitat is not a form of poverty sensationalism, but a moving treatment of its citizens’ lives, and was created by Bangladeshi and Korean artists. It was difficult to tell if the soundtrack was chosen as a feel-good lure to make people watch, or if it was meant to elaborate the excitement felt by the children, who did not despair but in fact enjoyed mugging for the camera and showing off their village.

Gazi Nafis Ahmed. Inner Face series, 2014; installation view. Courtesy of the Artist, Dhaka Art Summit, and Samdani Art Foundation. Photo: Jenni Carter.

This impulse to document social issues was also central to Gazi Nafis Ahmed’s photos of gay Bangladeshis in his project Inner Face (2013–2014). According to the artist, the acceptance of sexual diversity in Bangladesh is very low, and the LGBT community lives in the margins. His work follows a photojournalistic aesthetic of cropped black-and-white shots with strong contrasts; quotidian images that feature lovers in casual contact introduce an intimacy between the artist and his subjects that is passed on to the viewer. The artist movingly, compassionately captures the inner lives of his subjects, and his explicit intention is to use photography to advance social inclusion and acceptance of these marginalized people.

Rasel Chowdhury. Railway Longings, 2011-2015; installation view. Courtesy of the Artist, Dhaka Art Summit, and Samdani Art Foundation. Photo: Jenni Carter

Rasel Chowdhury, who won the Samdani Art Award, presented an extensive series of small landscape photographs titled Railway Longings (2011–2015). Born in the town of Jamalpur but now residing in Dhaka, Chowdhury determined to walk the 181-kilometer stretch of rail line that was once the only way of traveling between these two towns. The artist is interested in the rapid pace of development and environmental change in Bangladesh, and the impressive series of photographs he presents chronicles these changes in complex and perceptible ways, mixing nostalgia with a fascination for a landscape in transformation. The artist photographs station buildings and the people he meets along the tracks, and he uses the orthogonal of the rail lines in every imaginable way. The most impactful images are those that feature industrial buildings and shantytowns that crowd the railway lines when they reach the capital.

Shumon Ahmed. When Dead Ships Travel series, 2015; installation view. Courtesy of the Artist, Project88, Dhaka Art Summit, and Samdani Art Foundation. Photo: Jenni Carter

In another series of photographs, When Dead Ships Travel (2015), Shumon Ahmed presents another side of landscape and change in Bangladesh through the subject of shipbreaking. The industrial practice of taking cargo ships apart piece by piece has been memorably chronicled by Edward Burtynsky, but Ahmed’s images are less didactic and more replete with pictorial complexity. These images are, for the most part, blurry, and a single panoramic image can be broken into multiple exposures so the shoreline is repeated and seems to stretch on forever. It is not merely that the artist is toying with the border between abstraction and documentation; the nature of his imagery points to a difficulty in perception and to the impossibility of grasping the work of taking apart by hand an industrial structure the size of a small city. The pictorialist aesthetic that the artist sometimes employs references Stieglitz and Steichen, who were celebrating the arrival of modern life in New York; Ahmed seems instead to salute its demise on the shores of Bangladesh.

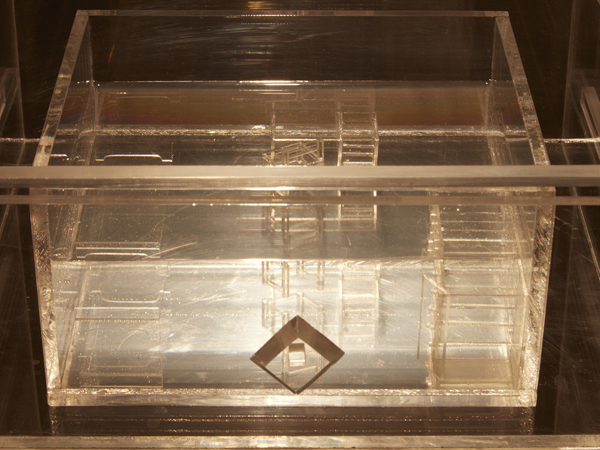

Shimul Saha. Rebirth, 2012; installation view. Courtesy of the Artist, Dhaka Art Summit, and Samdani Art Foundation. Photo: Jenni Carter.

The documentation of social forces is not the only refrain in Dhaka. Another view is provided by Shimul Saha, whose sculpture Rebirth (2012) is a transparent dollhouse of Plexiglass. Saha is an artist who experiments widely with materials and light, but this work is both a basin and a model of the artist’s bedroom, representing the two lives he has lived, both in the world and in his mother’s womb. The dual nature of life the artist addresses, combined with the crystalline beauty of the transparent model house, brings to mind the ideal conditions of an artistic life. To make art is to make an alternative world, and this perfectly calibrated object generates an apparent beauty and a vivid energy. Looking at the world reveals many complexities, but it is sometimes necessary to look inside to seek the principles that move the artist to create. In this sincere and haunting evocation of life, it is clear that “something was going on there.”