Mexico City

Gilberto Esparza: Cultivos at Laboratorio Arte Alameda

Sheltered by darkness, a mysterious octopus-like artifact lies in the nave of the Laboratorio Arte Alameda, a contemporary art museum housed in what was once an ancient convent. Capable of creating light and life by itself, the machine artifact operates by complex mechanisms. Twelve cylinders containing microbial fuel cells are connected to a main Plexiglas tank that houses plants in its interior. Every cylinder carries wastewater from various rivers and sewers of Mexico City and its suburbs. The bacterial communities living in each cell establish a symbiotic relation with the apparatus core, producing electricity through their metabolic processes. The resulting light allows the plants inside the main tank to photosynthesize. Despite the sci-fi atmosphere, we are not in film set, but in Mexican artist Gilberto Esparza’s installation PLNT_S TFTSNTTC_S. Plantas Autofotosintéticas [Autophotosynthetic Plants] (2013–2014)—one of the three main projects in his exhibition Cultivos [Cultures].

Gilberto Esparza. Plantas Autofotosintéticas [Autophotosynthetic Plants], 2013-2014; polycarbonate, carbon fiber, stainless steel, silicone, acrylic, electronic circuits, waste water, and aquatic ecosystem. Courtesy of Laboratorio Arte Alameda.

As stated by curator Tatiana Cuevas, Esparza mixes robotics, engineering, biology, and art, creating hybrid prototypes in order to imagine new solutions for environmental issues, such as our increasing amount of technological waste and water pollution. The zoomorphic robots and lab experiments in Cultivos [Cultures] emphasize parasite strategies, as well as sustainable devices that aim to reverse the destruction in many ecosystems.

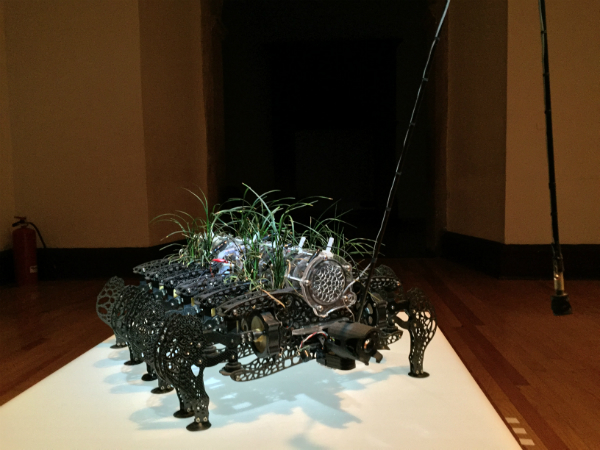

In PLNT_S NMD_S. Plantas nómadas [Nomad Plants] (2008–2014), an autonomous, multi-legged robot plays a leading role in the utopic quest for the improvement of polluted water and the rescue of native flora. With a special hose, this crawling device has the ability to suck wastewater and transform it on many levels. The water is filtered by microbial communities in charge of biodegrading organic wastes and eliminating toxic substances. With the energy this process creates, the mechanical critter recharges its battery and can walk around to look for more polluted liquid sources. On its back, many autochthonous plants grow, and the required and essential nutrients for their growth are obtained through the filtered water stored in the robot’s structure. A series of drawings that resembles a codex, MMVIII Fitocresta Errantis (2014), illustrates the robot’s origins, functions, and future hopes. A video of the piece being tested by the Santiago riverbank in Jalisco is also on display.

Gilberto Esparza. Plantas Nómadas [Nomad Plants], 2008-2014; carbon fiber, graphite, stainless steel, acrylic, silicone, crystal, electronic circuits, sensors, plants. Courtesy of Laboratorio Arte Alameda. Photo: Tania Puente.

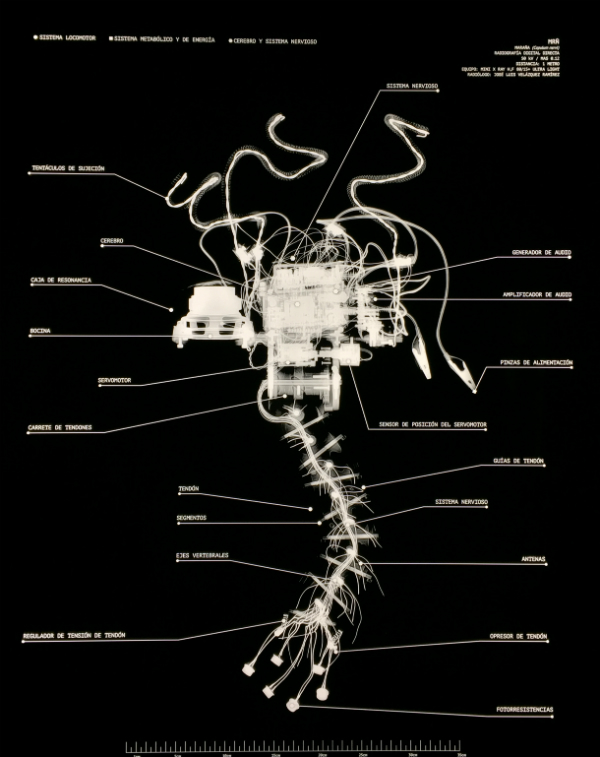

PRST_S RBN_S. Parásitos Urbanos [Urban Parasites] (2006’2007) completes the triad of works. As if humanity’s trash-disposal problems weren’t enough, technological waste now represents a new and more destructive threat to nature and civilization. Gilberto Esparza and his team collected circuits, pipes, wires, cells, panels, motors, and other mechanical and electronic components to build robotic organisms, “urban parasites” capable of feeding from power lines and communicating with fellow machines. In a subtle but noticeable way, with their movements and functions, these robots cast sounds that broaden the rich and complex urban soundscape, interfering with the city’s regular soundtrack. In the exhibition, these recycled technological critters are kept inside display cases. As with Plantas Nómadas [Nomad Plants], there is also a video that shows how these robots interact as undercover agents, gliding through power lines and encountering other parasites, producing sounds, and taking advantage of their renewed life. If visitors feel curious about their structural design, they can take a look at X-rays that specify the body parts and metabolic systems of these urban parasites.

In the early 19th century, when science was taking shape as a rational discipline and when the theories and frameworks of museums as we know them today hadn’t yet been created, cabinets of curiosities stood as spaces and vehicles for the public display of astonishing objects and experiments. Since travel was a rare activity for the masses, the cabinets provided an opportunity for individuals to get a glimpse of previously unimagined natural and human treasures. Scientific interest tended to dictate the way curiosity cabinets were assembled; objects such as fossils, plants, and monstrous vestiges were expected to be included, and imagination would be the key in speculating or deciphering their mysteries.

Gilberto Esparza. Maraña (Capulum Nervi), 2007; X-ray. Courtesy of Laboratorio Arte Alameda. Photo: Tania Puente.

This perplexing feeling can be found in Cultivos, where Gilberto Esparza’s works are accomplished with the highest degree of quality and enviable technique. His artifacts were invented to imagine solutions for our gigantic and barely reversible environmental issues. Nevertheless, the exhibition becomes a cabinet of wonder, since the very much needed reflection on these universal problems is relegated to a secondary place by the exoticism implied in the robots. Even several features of the 19th century era appear, like the Latin taxonomies assigned to every machine and the display arrangements for the pieces; by being placed inside cases and cabinets, these objects evoke fossils and civilizational remains from a distant time. Viewers may find themselves marveling at the construction of these devices while struggling to understand the scientific and technological background that sustains the projects. The information provided can be strictly technical for everyday people, and not quite complete or deep enough for specialists. Despite conceiving of the museum’s ground as a center for knowledge, Cultivos falls short on the reflective process for visitors acknowledging their responsibility, role, and required action on these environmental issues.

Gilberto Esparza: Cutivos is on view at the Laboratorio Arte Alameda in Mexico City through February 21, 2016.