Hashtags

#Hashtags: Dominion

#museums #empathy #posthuman #Anthropocene #environment

Recent headlines demonstrate that human beings are consistently terrible to one another, and it can be tempting to reject the human altogether. Drained by a year of public and private deaths, numb with exhaustion after having a child and returning to work, I entered Diana Thater’s mid-career retrospective at LACMA and found that those worldly concerns quickly fell away. Thater’s lush visuals and tranquil tone are a balm for shattered nerves, evocative of minimalist light sculptors like James Turrell and Anthony McCall, but rich with representational, political content. Thater’s work with animals suggests that what is universal about human beings is best understood by looking at the other creatures with whom we share the planet. For Thater, it is not enough to promote a caretaking vision of the planet, which would preserve the place of the human as the owner of all living things. In her work with animals and insects (including monkeys, dolphins, bees, and butterflies), she attempts to renegotiate the relationship between observer and observed. The human is present but not the priority when she is filming the works, and the presentation seems at times intended to introduce gallery visitors to the animals’ points of view. This work anticipates a posthuman future, in which we still exist but our dominance over other living creatures is no longer assumed.

Diana Thater. Life Is a Time-Based Medium, 2015; three video projectors, three lenses, player, and Watchout system; dimensions variable; installation view, Hauser & Wirth, London, 2015. © Diana Thater. Courtesy of Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Alex Delfanne.

One of the core beliefs held by all Abrahamic religions is that the creator specifically chose human beings to be the wardens of the Earth and all of its abundant life. Some interpret these doctrines as advocating a caretaking role toward the environment, while others have taken them as permission to consume natural resources with abandon. Different belief systems give representatives of the natural world equal stature to anthropomorphic deities, but Abrahamic faiths situate man at the pinnacle of a hierarchy that includes women, animals, insects, and plants. Maria Sibylla Merian and Rosa Bonheur, among others, used this myth of women’s closeness to nature to develop careers as artists on the basis of their depictions of plants and animals, at a time when other women were not permitted to pursue artistic practice professionally. Thater’s work resonates with this historical context, being both informed by and disinterested in the fact of her gender.

Diana Thater. Untitled Videowall (Butterflies), 2008; six video monitors, player, one fluorescent light fixture, and Lee filters; dimensions variable; installation view, 1301PE, Los Angeles, 2008. © Diana Thater. Courtesy of 1301PE, Los Angeles. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

Thater’s mid-career retrospective at LACMA has many things in common with 2014’s blockbuster Pierre Huyghe exhibition at that museum, including modified architecture, immersive projections, and live animals as subjects. Huyghe, I have argued, subjugated animal actors, including an Ibizan hound, hermit crabs, and honeybees, to his own and the audience’s desires by removing them from their typical environments and introducing them into unnatural situations in the galleries. Calling herself a “National Geographic wannabe,”[1] Thater’s approach is to introduce images of animals in their home environments into museum and gallery spaces that she modifies both physically and perceptually through projection mapping. These installations transform viewers’ sense of self through scale and location. Thater’s base in Los Angeles permits her access to professional documentary and cinematic techniques and aesthetics. Her work is motivated by her concern for representation as a site of potential objectification, a tendency that she claims to counteract by foregrounding the subjectivity of her animal sitters. “I’ve always been fascinated by nature and who animals might be, not who we make them into,”[2] she explains. It’s questionable whether an artist can really do this while still creating artworks for and by humans. Still, Thater does not appear to treat her animal subjects like performers or interfere with them while filming.

Diana Thater. Knots + Surfaces, 2001; five video projectors, sixteen-monitor video wall, six players, and Lee filters; dimensions variable; installation view, Dia Center for the Arts, New York, 2001. © Diana Thater. Photo ©Fredrik Nilsen.

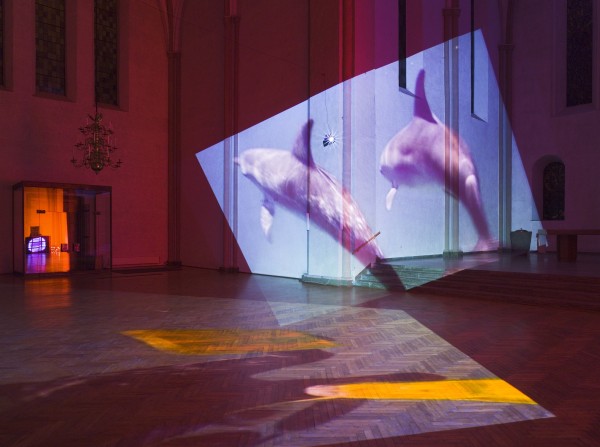

The artist encourages visitors to negotiate one another within the gallery spaces. Entering the blue-tinted lobby, one feels an immediate cooling-off from the persistent LA sun. There is another sun here, a cool one, burning green on a monitor. Immediately, what viewers know as a normal relationship to color and light has been interrupted. Another set of monitors stacked in a grid displays an array of six suns in isolated primary and secondary colors, casting a glow that can be seen from an adjacent gallery. In the projected space of Knots + Surfaces (2001), audience members are dwarfed by dancing honeybees; the bees’ environment and dance is derived from the writing of mathematician Barbara Shipman, who used honeybees as a model for understanding time in six dimensions. “Shipman realized that bees are actually speaking about six dimensions, so that to read the dance of the honeybee is to read information about quantum fields in their natural state,”[3] the artist explains. In a different gallery, Delphine (1999) consists of multiple projections on the walls, ceiling, and floor depicting dolphins at play; the existing architecture is renegotiated to align human movements in the space with the dolphins’ movements and environment. As in open water, the animals pass above, below, and alongside the bodies of viewers.

Diana Thater. Delphine, 1999; four video projectors, five players, nine-monitor video wall, and Lee filters; dimensions variable; installation view, Kulturkirche St. Stephani, Bremen, Germany, 2009. © Diana Thater. Photo: © Roman Mensing/artdoc.de.

Another work, Chernobyl (2010), incorporates footage shot at the eponymous site of a catastrophic nuclear accident in 1986. Drone footage reveals that much of the 120-mile circle of the now-uninhabited Chernobyl Exclusion Zone has been overtaken by plants and wildlife. Thater explores the new inhabitants and the human remnants of this lost place. The installation, projected onto three walls, is immersive, and its subject is mythic and terrifying. The detritus of abandoned towns speaks to the insignificance of our time as individuals, and as a species. The disinterested glances of wild horses milling about remind us that our capacity to control our surroundings is more limited than we like to think.

Life Is a Time-Based Medium (2015) is a massive projection of a temple built into a cliff face near Jaipur, India. The structure is a façade, appearing inaccessible to humans but populated by a community of monkeys who climb between arches and pillars. Their tiny bodies can occasionally be seen crawling up the temple’s face. The huge scale of the Galtaji Temple, dedicated to the Hindu monkey god Hanuman, situates the human at the level of monkey and at a distance from the divine. Inside a scallop-cut doorway, a more intimate perspective on the monkeys is offered, but still at a remove. The close-ups are framed within a movie screen, complete with a row of seats, a wry nod to the reality that all of this will be simply entertainment to most visitors. Despite her self-referential gesture, Thater’s rumination on the monkeys opens up the possibility of a spiritual plane accessible only to nonhumans.

Diana Thater. Life Is a Time-Based Medium, 2015; three video projectors, three lenses, player, and Watchout system; dimensions variable; installation view, Hauser & Wirth, London, 2015. © Diana Thater. Courtesy of Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Alex Delfanne.

In contrast to Huyghe, whose work situates animals within artificial contexts in the manner of an aestheticized circus, Thater appears more concerned with representing the animals’ uninterrupted existence to her audience. She works against the Enlightenment inheritance that plagues Huyghe, who encourages exploitation of animals for the benefit of human contemplation and entertainment. Neither artist can claim to be any closer in proximity or understanding to the animals they represent than the other. While Huyghe consistently positions animals as foils for reflection upon the human, Thater means to liberate us from our self-absorption. Both artists create spectacular visions, dazzling in their technical and visual splendor. Thater’s strength is in her ability to recede and allow her subjects to take the lead. If we are to survive the Anthropocene as a species, we will have to learn to follow her example.

Diana Thater: The Sympathetic Imagination is on view at LACMA through February 21, 2016.

#Hashtags is a series exploring the intersection of art, social issues, and global politics.

—

[1] Friere Barnes, “Diana Thater Interview,” Time Out London, April 7, 2015: http://www.timeout.com/london/art/diana-thater-interview (accessed December 13, 2015)

[2] Ibid.

[3] Melinda Barlow, “Sculpture and Architecture in Dialogue: A Conversation with Diana Thater,” Sculpture Magazine (Vol. 20, No. 8, October 2001): http://www.sculpture.org/documents/scmag01/oct01/thater/thater.shtml (accessed December 13, 2015)