Atlanta

Sheila Pree Bright: 1960Now at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia

1960Now, on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia, is an expansion of photographer Sheila Pree Bright’s continued interest in naming and documenting the unknown leaders of African American social movements: the influential agitators, groundbreakers, and activists whose names might not have been Rosa, Martin, or Malcolm. In her latest photographic project, Bright points to a new generation of faces experiencing frustrations and conflicts that are as new as they are old. Comprising photographs, films, and an interactive project, 1960Now carves out a world of images that connects individuals, struggles, and stories from previous and ongoing civil-rights movements without conflating or collapsing the specificity of those histories. In Bright’s work, the old and new are unshakably connected by the dialectical and ever-changing “now.”

Sheila Pree Bright. 1960Now, 2015; installation view, the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia. Courtesy of the Artist.

Neither scattered nor arranged, spontaneous nor precise, oversized black-and-white photographs lie on the floor, inches away from the gallery’s outer perimeters. The powerful presence of voices, faces, and traces of the bodies captured within these images are immediately striking. Brightly lit faces sit square within the repetitive rectangular form—awake, alive, and uncompromising. The installation refuses the normal conditions of visual engagement in two-dimensional art—an engagement that normally demands an equal confrontation and leveling of space between the viewer and the viewed. Through this gesture, Bright demands that we turn our heads down to look at and regard individuals who command and reclaim our gaze. The experience is as profound and poignant as it is uncomfortable. Illuminated in front of a stark white background, Bright’s work collapses the conditions of the studio portrait and the uniformity found within institutional photography (passport photos, mug shots, photo IDs, driver’s licenses) to create images that carry the weight of the shared history and contingent experiences of these individuals. Size and scale play an important role as well in the filmic element of the exhibition that gives voice to the unique experiences and perspectives of these social agitators, thus animating the photographs that lie powerful in their silence around the room.

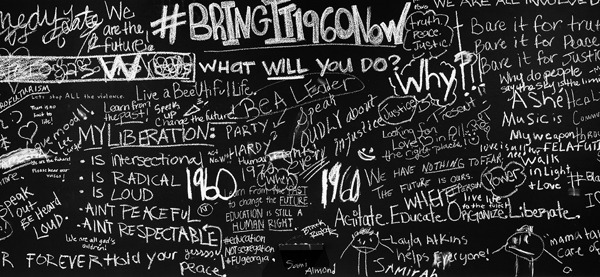

Sheila Pree Bright. BringIt, 2015; chalkboard; installation view, 1960Now, The Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia. Courtesy of the Artist.

BringIt is an interactive project consisting of blackboards that stretch across the open wall space. Interrupting the floor space of the photographs, the ever-evolving piece is scrawled with chalk-written notes, which electrify the room with a visual language that embodies contemporary activism today. Filled with hashtags, slogans, mantras, and graffiti written by the people for the people, BringIt opens up the static portraits to a world constantly in the process of being written and connects the struggles of bodies across the nation and throughout the world. Undertaken and activated by the community, the project creates paths of inclusiveness within the gallery, turning text into indexical affirmations of the spaces and sites outside of the context of the museum.

Bright’s work refuses all notions of the passive subject—a difficult outcome to achieve, given the rocky historical relationship between the media and social movements across the span of the last century, from the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire in New York City in 1911 to Ferguson, Missouri. The gap between what is represented as “documentary” evidence by the media and the reality of the experience on the ground is a problem that continues to inform the history of civil dissent, particularly when it involves media coverage of institutionally marginalized and oppressed groups. Bright’s photographs weigh in on the loaded politics of the African American objector in representation by recoding the inherent nostalgia of black-and-white photography and film. By using genres that call up powerful emotions of past struggles that continue to shape our understanding, Bright ambiguously provides the affinities and ruptures between past and present race struggles.

Sheila Pree Bright. 1960Now, 2015; installation view, the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia. Courtesy of the Artist.

In his groundbreaking text on the photographic documentation of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, Maurice Berger highlights the determined efforts of the white press to frame any acts of black resistance as nonthreatening, thereby casting blacks in roles of limited power, and minimizing the bravery and accomplishments of those who were risking their lives on a daily basis.[1] Even within the photographs that captured the physical violence of white supremacists, blacks were cast as passive victims within a black-and-white image world, with the effect of “focusing white attention on acts of violence and away from historically rooted inequalities.”[2] Projected across the upper ridge of the gallery wall, Bright’s films refuse the media’s emptying of meaning and objective in acts of resistance, and reverberate with the experiences of those who witnessed and participated in the trajectory of protests, old and new. The videos allow actors and agents of protest movements to speak for themselves, with testimony and footage unbound by the biases, perspectives, and edits of the 24-hour televised news cycle.

Bright’s careful mediation of and attention to contemporary eruptions of African American action—bodies in the streets, moving forward, united in rage and care for the other—asks us to break our notions of difference between past and present, passivity and progress, in order to see that the cause of Martin, Malcolm, and Rosa is both continuous and discontinuous, aligned while moving forward toward its own unique position.

[1] See Maurice Berger’s Seeing Through Race: A Reinterpretation of Civil Rights Photography (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011).

[2] Ibid., pg. 34–35.

Sheila Pree Bright: 1960Now is on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia in Atlanta through November 28, 2015.