Summer Reading

Summer Reading – The Past Is Present: The Curatorial Act of Exhibiting Exhibitions

Today’s selection for our Summer Reading series comes from our friends at un Magazine. Author Pippa Milne examines curatorial reconstruction, noting that it “emphasi[zes] the relevance of the exhibition as a singular, unified cultural and historical phenomenon; an irreducible embodiment of the relationship between curator, artist, and artwork.” This article was originally published in issue 7.2.

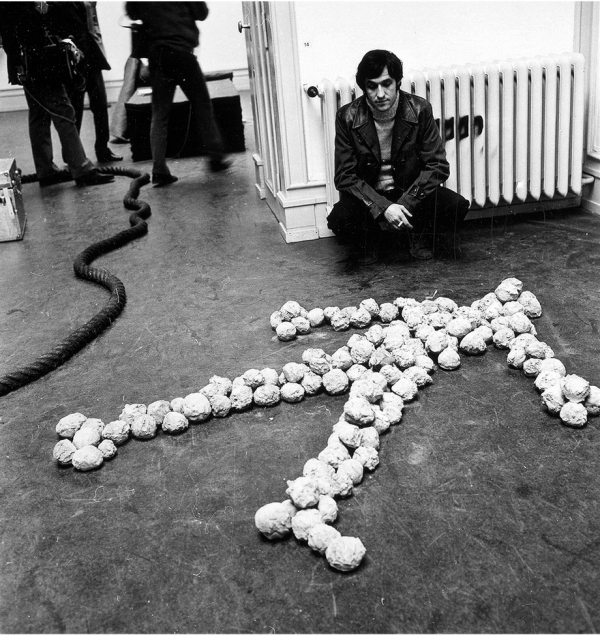

Alighiero Boetti with lo che prendo il sole a Torino il 19 gennaio 1969 (Me Sunbathing in Turin, 19 January 1969), 1969, from ‘When Attitudes Become Form’, Kunsthalle Bern, 1969 photograph: Shunk Kender, ©Roy Lichtenstein Foundation.

It sounds like an art-world joke: What do you get when you pluck a 1969 exhibition from a German Kunsthalle and reconstruct it in an 18th-century Venetian palazzo, forty-four years later? Add some gallery attendants in Prada suits and an audience fresh from Massimiliano Gioni’s 55th Venice Biennale, and you have an answer that, due to the arcane specificity of its starting point, might only be interesting to in-on-the-joke art academics and curators. But to them, it’s an intriguing, extravagant, and ludicrous experiment.

Bear with me a moment. You’re in Venice. You’ve walked into Ca’ Corner della Regina, entering from a back street near San Stae Vaporetto stop rather than via the private jetty. After being greeted by an immaculately dressed attendant from Fondazione Prada with a neutral expression and a lilting accent, you walk through the classical foyer and up the stairs, past a square of wall that has had the plaster removed from it, past several sacks of coal, grains, and beans, and under some black wires. You’re following the vocal intonations of Josef Beuys as he chants “Ja ja ja ja! Nee nee nee nee!” There is a strange sense that this construction is a diorama of a past environment—as though you are standing in front of a group of antelope, set in their painted wilderness in a wing of the Museum of Natural History. The habitat is recreated as succinctly and loyally as possible; the objects of interest have been placed in their most natural positions, as per the investigative research conducted by curators and historians. But it still doesn’t look real. It’s a bit stuffed. There are small gaps between the fresh, constructed walls and the ornate architraves and frescoed panels. The stage set is obstinately obvious, saving it from fetishism. This is not Madame Tussauds. This is a conflation of two spaces, two temporal instances. It’s convincing, but not trickery.