New Orleans

Ten Years Gone at the New Orleans Museum of Art

In the aftermath of a catastrophe, memorialization and remembrance are inevitably tied to forms of forgetting. These often take the shape of reactionary modes that proclaim an urgent desire to smooth over the eruptive, unresolved conflicts that shape our collective past and place them into digestible modes of representation.[1] However, for the communities that bear witness to the impact of a disastrous event, forgetting is impossible, as the harsh realities of the event continue to manifest themselves economically, socially, geographically, and spiritually.

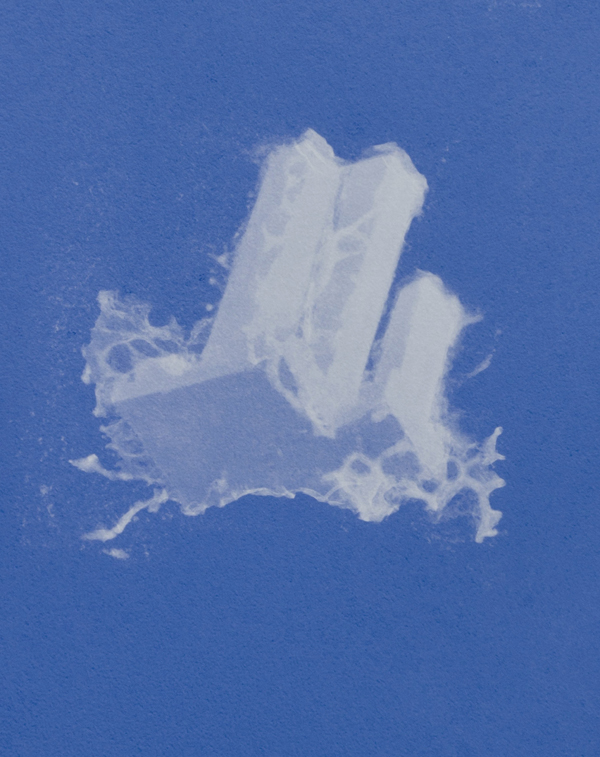

Christopher Saucedo. World Trade Center as a Cloud (No. 5), 2011; linen pulp on cotton paper; 60 x 40 in. Courtesy of the Artist.

The New Orleans Museum of Art’s current exhibition Ten Years Gone—timed to coincide with the tenth anniversary of Hurricane Katrina—draws attention to the phenomenological fabric of disaster by making powerful connections between the messy temporal structures that animate traumatic events, cycles of life, and art itself. Despite strong aesthetic and contextual differences between the six artists chosen for the exhibition, curator Russell Lord has woven together a polyphonic conversation that explores disaster as a way to understand tragedy as something forever in the process of becoming. Here, time oscillates between the roles of organizing principle, conceptual conceit, and metaphor for the untidy “unfinished-ness” that often marks complex events, as the potency and infallibility of art to fully re-present the past is explored with vigor.

Willie Birch. Crawfish Dwelling, 2009; bronze; 6 x 5.5 x 4 in. Courtesy of Willie Birch and Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans, LA.

In an effort to avoid imposing a sweeping narrative of Katrina based on progress ten years from the event, or upon unreflective or sentimental modes of interpretation, many of the works chosen for the exhibit respond to an expansive field of issues, namely, the costs of catastrophe and the fragile equilibriums that sustain life on Earth. The thin net between the losses that continue to injure the citizens of New Orleans—who lost family members, neighbors, homes, personal belongings, and pets to the floodwaters—and the environmental losses brought on by the storm are felt most intensely in the works of New Orleans native Willie Birch. While Birch’s casting in bronze of the natural byproducts of Louisiana’s infamous crawfish population in Crawfish Dwelling (2009) speaks to the ecological losses suffered in the aftermath of the storm, it is also a meditation on the profound interdependency between human culture and the natural environment, casting new light on what is precious in today’s society. Also reflecting on disasters that captured the attention of the international media, Christopher Saucedo’s delicate work World Trade Center as a Cloud, No. 5 (2011) opens up crucial links between the devastations in New Orleans and the catastrophe of 9/11, and invites the viewer to consider the disturbing relationship between the events, namely their mutual grounding in human error, failed standards of government accountability and transparency, and the human costs of long-standing environmental, energy, and shipping policies.

Nicolas Nixon. The Brown Sisters, New Canaan, Connecticut, 1975. © Nicolas Nixon. Courtesy of Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, CA.

The final galleries dissolve the specificity of the exhibition’s tone into a poignant meditation on the cyclical patterns of renewal and transformation that structure human life through the time-dependent media of video and photography. Canadian artist Spring Hurlbut’s 2008 video work Airborne manipulates the material components of death—cremated ashes—into a balletic contemplation of the dynamic impulses animating life, and of the inexplicable abstraction that loss and death involve. However, it is Nicolas Nixon’s long-term photographic project documenting his wife and her three sisters over the span of forty years that proves to be the most irresistible to viewers in its direct and disquieting engagement with the mortality of its sitters. Simple, visually crisp, and equally intimate and coolly combative, Nixon’s finale to the exhibition foregrounds the power of photography to conjure materialist modes of remembrance and duration by documenting the passing of time through the faces and figures of aging individuals. Closing the exhibition with a family portrait—a genre of photography that embodies the act of “coming together”—Ten Years Gone shapes a utopian vision for the future of New Orleans as a city marked deeply by its traumatic past, moving forward nevertheless into the future with hope and love.[2]

Ten Years Gone is on view at New Orleans Museum of Art through September 7, 2015.

[1] For more on the art of commemoration and catastrophe, see: The Politics of War Memory and Commemoration, eds. TG Ashplant and Graham Dawson (New York: Routledge Press, 2013); Patrick H. Hutton, History as an Art of Memory (Hanover: University Press of New England, 1993); and Robert S. Nelson and Margaret Olin’s Monuments and Memory, Made and Unmade (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004).

[2] My deepest thanks must go to New Orleans Museum of Art’s Freeman Family Curator of Photographs, Russell Lord. During a telephone interview on June 29, 2015, Lord referred to the exhibition as an opportunity to “gather these artists together in order to ask questions about what was intended by the commemoration of the ten-year anniversary, and what has and has not been achieved.”