Hashtags

#Hashtags: Heart of Darkness

#imperialism #appropriation #representation #environment #postcolonialism #revolution

Throughout the 56th Venice Biennale, one finds national pavilions that have taken up the postcolonial mantle of Okwui Enwezor’s central exhibition within the contours of their own relationships to imperialist histories. Among the most successful of these are Vincent Meessen’s Belgian pavilion, Personne et les Autres, and Fiona Hall’s Australian pavilion, Wrong Way Time. Both pavilions consider how the definition of nationalism has expanded in the past twenty years to include representations of communities formerly excluded, while using that newfound inclusion to reinforce rather than reexamine the power structures that historically promoted exclusion. In short, they consider—and in some ways demonstrate—how cultural appropriation has developed as a nationalist strategy in an increasingly post-national world.

Vincent Meessen. One.Two.Three, 2015; video. Courtesy of the Artist and Normal, Brussels. © Vincent Meessen. Belgian Pavilion, 56th Venice Biennale.

At the Belgian pavilion, Meessen and curator Katerina Gregos have invited nine other international artists to contribute works that question the European origins of Modernism in the context of global trade and conquest. The artists—Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc, Sammy Baloji, James Beckett, Elisabetta Benassi, Patrick Bernier & Olive Martin, Tamar Guimarães & Kasper Akhøj, Maryam Jafri, and Adam Pendleton—represent Africa, Latin America, South Asia, the United States, and Western Europe. Historically, Belgium was the first nation to open a pavilion in the Giardini at Venice, financed by the regime of King Leopold II with funds gained through brutal colonial oppression in the Congo. Today, Belgium is the seat of the European Union, and a country that struggles to reconcile its two distinct linguistic and cultural populations (Dutch-speaking Flemish and French-speaking Wallonians) with an influx of economic and political migrants from Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa. Inspired by these contexts, the exhibition reflects the manner in which the International Style of art and architecture, developed in the 20th century, succeeded and failed in its ideal of fostering utopian conditions around the globe during the era of postcolonial liberation.

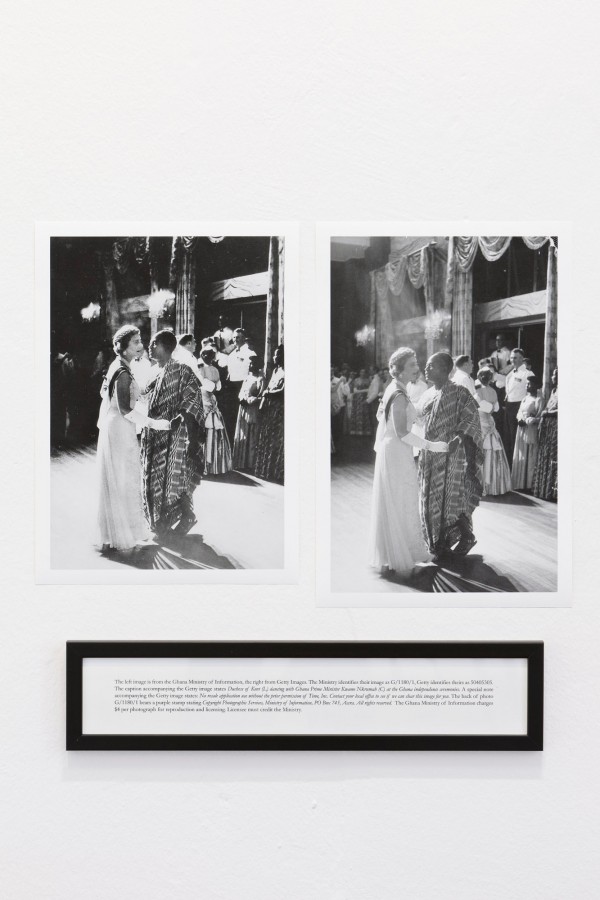

Maryam Jafri. Getty Vs. Kenya Vs. Corbis, 2012; installation view (detail), Belgian Pavilion, 56th Venice Biennale. © Maryam Jafri.

This is an enormous undertaking, resulting in a pavilion that feels overstuffed with clashing forms and volumes of archival content. The most successful include Elisabetta Benassi’s live reading of Mark Twain’s King Leopold’s Soliloquy, a satire of European colonial rhetoric read from a train-stop shelter composed of massive plaster bones; and Maryam Jafri’s photo and text installation, which contrasts documentary footage of the political transitions of midcentury African independence movements with the historical record as presented by multinational corporate information conglomerates such as Corbis and Getty Images. The question of who owns historical narratives is central to both works. Tamar Guimarães and Kasper Akhøj present an installation of minimal wall sculptures and slides that juxtapose the formal lexicon of Modernism with fragments of idealized rhetoric around cultural difference. The grouping of this work with James Beckett’s roboticized library of standard Modernist architectural forms, and Sammy Baloji’s use of archival photographs to demonstrate the use of mapping as a tool for segregation in urban planning, is poignant. The three artists underscore the limited ability of rational systems such as those promoted by Internationalist artists and architects to undo entrenched social and racial biases, pointing to how such methods may instead reinforce discrimination by cloaking it in objectivity. Meessen’s own contribution links political emancipation in Congo with Marxist-inspired liberation movements throughout the Global South and the May 1968 student uprising associated with the Situationist International, a group whose genuinely international origins (including a number of Congolese) have been obscured by Francophone nationalism in the ensuing decades.

Sammy Baloji. Essay on Urban Planning, 2013; twelve color photographs; 80 x 120 cm 320 x 360 cm. each; installation view. Courtesy of the Artist and Galerie Imane Farès, Paris. © Sammy Baloji. Photo: Alessandra Bello. Belgian Pavilion, 56th Venice Biennale.

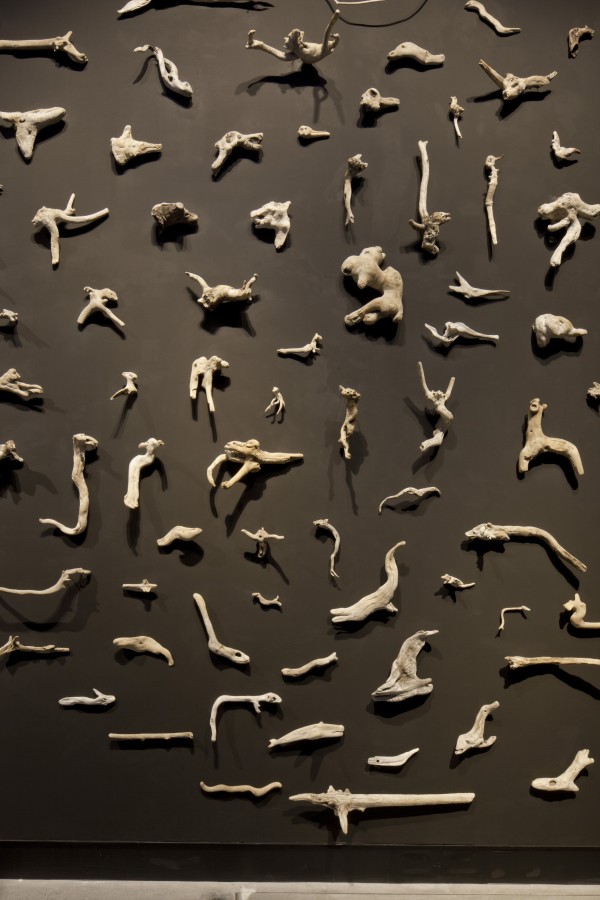

While the Belgian Pavilion is the oldest national venue in the Giardini, the Australian pavilion is the newest, debuting in 2015 with a solo exhibition by Fiona Hall curated by Linda Michael. Hall expands on the “hunting lodge” that she created for Documenta 13 in 2012 with a collection of sculptures based on the forms of indigenous folk art and archaeological collections. The interior of the pavilion is lined with glass display cases that connect Hall’s installation to Victorian-era museology, highlighting how these widely adopted systems of collection and display of art and visual culture are anchored in the values of the colonial period. Unlike Belgium, Australia has no history of conquest beyond its borders—rather, like the United States until the 20th century, its colonial project has occurred within the confines of its own land mass through systematic incarceration, brutalization, and cultural oppression of its Aboriginal people. In response to critique of this history, which included displacing a generation of Aboriginal children into boarding schools where they were stripped of their linguistic and cultural heritage, Australia has in recent years represented itself internationally through a collection of symbols drawn from indigenous sources. It remains to be seen whether this newfound appreciation of Aboriginal culture extends to improved opportunities and visibility for members of this deeply injured community.

Fiona Hall. Wrong Way Time, 2015. Australian Pavilion of the 56th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia, All the World’s Futures. Courtesy of la Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Alessandra Chemollo.

For her installation in Venice, Hall collaborated with eleven members of a collective of Aboriginal artisans known as the Tjanpi Desert Weavers, women from the Central and Western Deserts of Australia who employ traditional methods of sculpting animals from natural fibers, including native grasses. These materials, supplemented by shreds of Australian and British military uniforms supplied by Hall, were employed to create the forms of desert animals that have been eradicated by human population growth and climate change in the women’s lifetimes. The erasure of these animals parallels the decimation of Aboriginal communities. Says weaver Niningka Lewis, “I have a theory that our meat animals disappeared when we started to eat mai (white flour, sugar, and tea) […] These were our foods, and as soon as we switched foods to white people’s foods, the animals all disappeared.”[1] The loss of culture and the loss of nature are interconnected.

Fiona Hall. Wrong Way Time. Australian Pavilion. 56th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia, All the World’s Futures. Courtesy of la Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Alessandra Chemollo.

Hall’s installation resembles a historical display, but the title Wrong Way Time suggests that she is not concerned simply with resurrecting the past. The archive of objects and materials that she creates is instead a way of pointing out the magnitude of history and culture that has been lost to the colonial project. The gaping absence wrought by systematic erasure cannot be undone by creating new forms to replace the ones that were lost. Instead, the new forms become markers wrested from provisional materials, such as paper scraps and driftwood, that point to the impossibility of replacing what is missing. Both the Australian and the Belgian pavilions are anchored in the knowledge that the brutality of the colonial era cannot be undone through contemporary gestures toward reconciliation. Instead, contemporary artists wishing to engage with these themes must explore and reveal how overt colonial structures have become covert, yet still entrenched, in the postcolonial period.

All the World’s Futures—The 56th Venice Biennale is on view through November 22, 2015.

#Hashtags is a series exploring the intersection of art, social issues, and global politics.

[1] “Tjanpi Desert Weavers,” Fiona Hall: Wrong Way Time. Linda Michael, ed. (Australia Council for the Arts, Piper Press, 2015), 53.