New York

Zero: Countdown to Tomorrow at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

In Düsseldorf, West Germany, amid the tumultuous aftermath of the Second World War, two German artists—Heinz Mack and Otto Piene—founded Group Zero in 1957. Later joined by fellow German artist Günther Uecker in 1961, the three sought to reinvent art in the postwar era and create a vision toward a transformed future through myriad artistic forms: performance, painting, sculpture, exhibition, publication, film, and installation. In the years following 1961, Group Zero rapidly spiraled outward to encompass a remarkable network of international collaborators including the likes of Lucio Fontana, Yayoi Kusama, Yves Klein, Piero Manzoni, Jesús Rafael Soto, Jean Tinguely, and Herman de Vries.

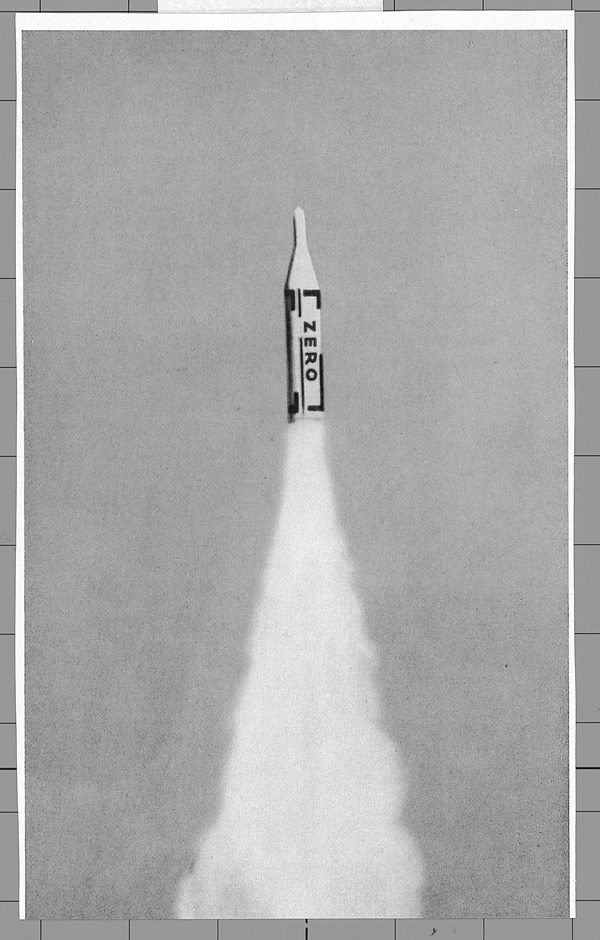

Illustration from ZERO 3, July 1961, design by Heinz Mack. Courtesy of Heinz Mack.

Zero: Countdown to Tomorrow, 1950s–60s, currently on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York (and two others, opening in 2015 at the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam), is the conclusion of a three-year research project undertaken by the Guggenheim, Stedelijk, and the Zero Foundation in Düsseldorf. Due in part to the exhaustive research efforts of the Guggenheim, Stedelijk, and Zero Foundation, Group Zero’s extensive network, and the ambitious material, social, and conceptual scope of their vision, the Guggenheim iteration of the exhibition is vast and informative.

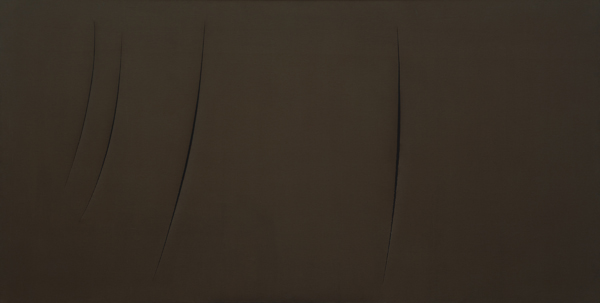

Lucio Fontana. Concetto Spaziale, Attese, 1959; synthetic paint on canvas, olive green; 125 x 250.8 cm. Courtesy of David Heald. © The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

The Guggenheim, as a large-scale exhibition space, is dynamic, inspiring, and wholly unwieldy. Seeing exhibition after exhibition confront the drama of Frank Lloyd Wright’s rotunda with renewed vigor reminds one of the importance of forgetting and of starting anew. Group Zero itself, an ungainly yet remarkably influential and hopeful constellation of artistic activity, is, at least conceptually, perfect for the Guggenheim. What better venue for Group Zero than one of Modern Architecture’s most famous and ambitious structures, which, further still, was finished in 1959 during the very formation of Zero?

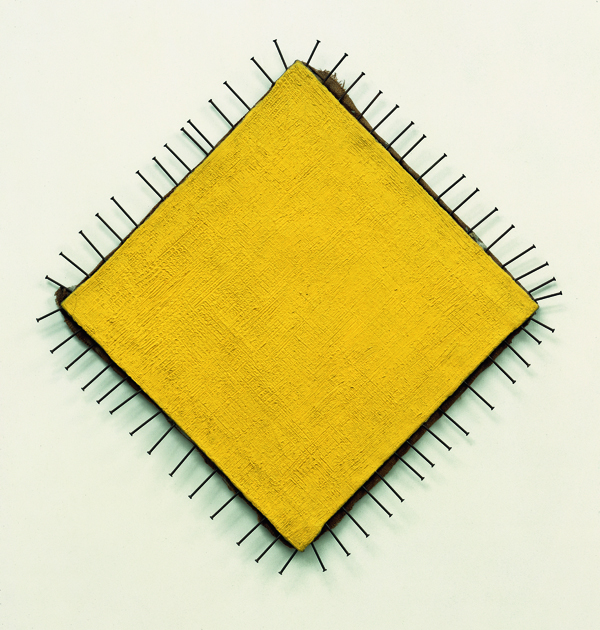

Günther Uecker. The Yellow Picture (Das Gelbe Bild), 1957–58; nails and oil on canvas; 87 x 85 centimeters. Courtesy of Nic Tenwiggenhorn.

In a notably smart gesture, Zero opens in the High Gallery—a small offset space recessed at the beginning of the first twist of the rotunda—with a restaging of the 1959 exhibition Vision in Motion—Motion in Vision, work by Group Zero-affiliated artists that originally took place at the Hessenhuis in Antwerp, Belgium. The Vision in Motion exhibition was an important starting point for Group Zero, and the restaging, complete with black walls, paintings, and sculptures that hang from the ceiling on thin wires, demarcated by the artists’ names written on the floor, opens Zero quite dramatically.

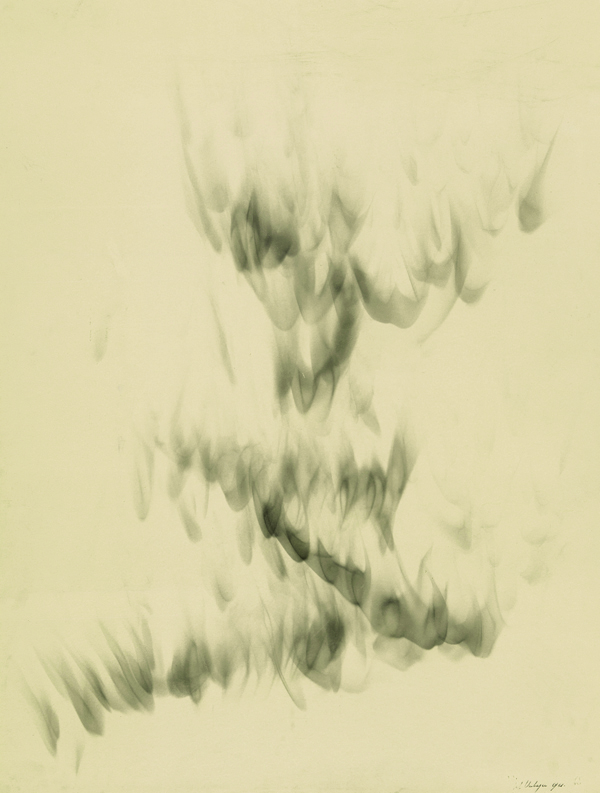

Jef Verheyen. Untitled, 1961; soot on paper; 70 x 53.5 cm. Courtesy of Herman Huys, courtesy Galerij De Vuyst.

As one continues up the rotunda, works by Tinguely, de Vries, Fontana, Klein, and numerous other artists are displayed in small vignettes that detail the new stylistic tropes and forms Group Zero was working to define: monochrome, serial structure, works made with fire and smoke, small kinetic and light sculptures, and three-dimensional sculptural painting that often included grids made from nails, corks, and thread.

Otto Piene. Light Ballet (Light Satellite) (top) and Light Ballet (Light Drum), 1969; chrome, glass, and light bulbs; sphere diameter: 38 cm; drum height: 45.7 cm, diameter: 124.5 cm. Courtesy of Moeller Fine Art, New York.

As the exhibition winds upward in seemingly unceasing spirals, these small vignettes—which also incorporate ephemeral material, documentation, and short films—begin to benignly overlap and wash one another out, leaving only the truly vibrant and strikingly kinetic works in the mind. Among these standouts is Günther Uecker’s New York Dancer I (1965), a totemic standing sculpture made from white cloth with long nails punctured through the surface with their sharp points protruding out, draped over an electric motor that activates every few minutes to shake the nail-laden cloth to create an incredible cacophony—simultaneously musical and chaotic yet almost functional and utilitarian in nature.

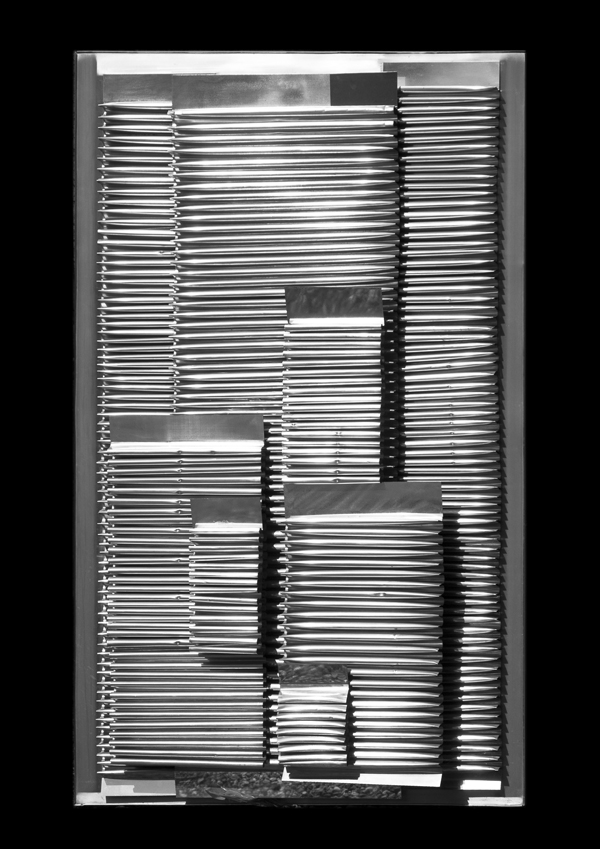

Heinz Mack. New York, New York, 1963; aluminum on wood;160 x 100 x 20 cm. Courtesy of Heinz Mack.

Yves Klein’s impossibly visual Pure Blue Pigment (PIG 1) (1957), re-created for the exhibition, was astounding. The work is a bed of pure Klein Blue pigment laid directly onto the floor of a recessed section of the uppermost level of the rotunda. The recessed floor, covered evenly in the pigment, is slightly angled; the point furthest away from the viewer is slightly higher than entrance. The combination of Klein’s blue pigment and the off-white walls of the Guggenheim make the work wholly engrossing.

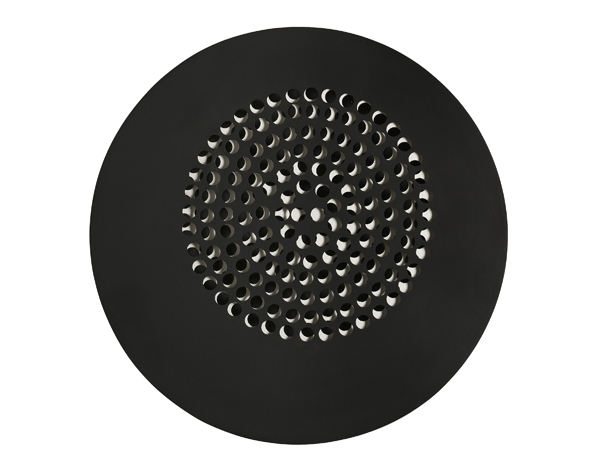

Pol Bury. Punctuation (Ponctuation), 1959; wood and electric motor; diameter: 70 cm. Courtesy of Patrick Derom Gallery, Brussels.

The high point and conclusion of the exhibition, literally and figuratively, is the re-creation of Light Room: Homage to Fontana (Lichtraum: Hommage à Fontana), which was originally presented at Documenta 3, Kassel, West Germany in 1964. Light Room is composed of nearly a dozen moving installations and sculptures made of wood and metal that incorporate movement and light. One work in the Light Room, titled Punctuation (1959), incorporates a flat wooden wheel standing nearly seven feet tall atop a wooden plinth like a solid rounded pinwheel. As the motor-driven wheel slowly turns, small slivers of light and shadow dance on the walls through a series of small holes carved in the face. The room, set like a stage, is filled with works like Punctuation, which turn on and off in unison a few times per hour. They emit a suite of lights and shadows that dance—swinging and tapping—along the curved, slightly cavelike wall in the gallery, offering a final bit of performance for the viewer who so laboriously climbed the rotunda’s path. Importantly, this room includes the only two works made collaboratively by the trio of Piene, Mack, and Uecker—a fitting culmination for an exhibition about the art movement instigated by the three.

Zero: Countdown to Tomorrow, 1950s–60s is a cacophonous and highly illustrative view into an often-overlooked and unheralded art movement. While the exhibition doesn’t fully convey Group Zero’s ideas, and becomes monochromatically muddy at times, it does extol the importance of Group Zero and its fundamentally hopeful, ambitious, and creative platform.

Zero: Countdown to Tomorrow, 1950s–60s is on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York though January 7, 2015.