Los Angeles

Stan VanDerBeek: Poemfield at the Box

From the malevolent mainframe of 2001’s “Hal” to the proliferation of remote-controlled, drone-delivered destruction, dystopian visions of technology exist in abundance. Even contemporary artists who work with technology, like Cory Arcangel and Wade Guyton, tend to focus on its glitches and limitations. By contrast, the Box’s dazzling exhibition of computer-animated films by Stan VanDerBeek offers a hopeful perspective on the promise of technology, one that still captivates almost fifty years later.

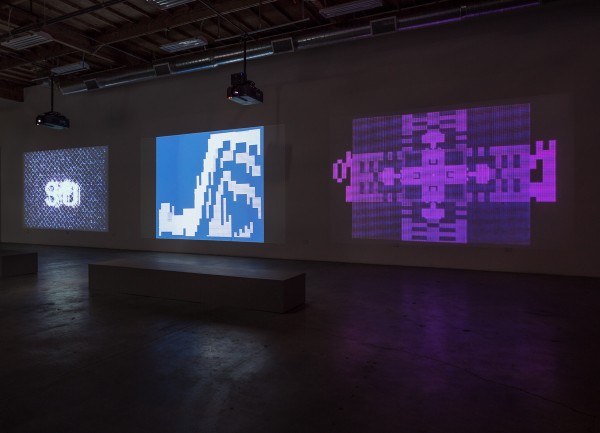

Stan VanDerBeek: Poemfield at The Box, Los Angeles; installation view. Courtesy of the Estate of Stan VanDerBeek and the Box, L.A. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

On view are five of the eight films that compose VanDerBeek’s Poemfield series, created between 1966 and 1971. They combine poetic texts and abstract graphics designed with an early computer language. Words emerge from a glittering mosaic of colored pixels, and then fade back into the blinking, swirling digital ground. With the exception of Poemfield No. 5 (1968), which uses footage of skydivers, all of the films represent purely computer-generated landscapes. The graphics transform and flicker at a frenetic pace while the poems slowly unfold over about five minutes. The visuals entrance and draw viewers in, but it is the enigmatic texts that hold the attention. VanDerBeek likened his films to illuminated manuscripts, wherein gilt illustrations would entice the reader to focus on the word.

The artist made these films at Bell Labs in collaboration with engineer Ken Knowlton, through Experiments in Art and Technology (EAT), an organization founded in part by Robert Rauschenberg. Knowlton had developed BEFLIX, perhaps the earliest computer animation language, which they used to write the scripts for the Poemfield films. These scripts were then run through a computer and channeled into a cathode-ray tube output that was filmed. Artists Bob Brown and Frank Olvey added color. The Box has transferred the original 16mm films to video and restored Poemfield No. 1 (1967) in HD; the difference is striking. The other films jump and stutter with wobbly focus, so that making out the words is a challenge, but the HD version is clear and sharp. This is especially true in a two-tone variant, Poemfield No. 1 (Blue Version), which strips away the color so that the original programming is highlighted. Restorations of the rest of the Poemfield series are hopefully underway.

Stan VanDerBeek: Poemfield at the Box, Los Angeles; installation view. Courtesy of the Estate of Stan VanDerBeek and the Box, L.A. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

VanDerBeek viewed technology as a source of potential liberation and empowerment, not alienation. This was true for the creation of art as well as for its ability to reach a wide audience. “What spellbinds me as an idea is that I’ll be able to sit someplace in a railroad station and write a movie, or maybe even pick up a telephone eventually and write a movie,” he said in the 1968 film Incredible Machine. He saw the ubiquity of television as an ideal vehicle for the dissemination of artwork. “If the world of the future is a world of ephemeral TV programs and houses which we change as often as we change cars, it may be a world which calls for an art as ephemeral as much of the music which eighteenth-century composers provided for social occasions. Art is more than eternal masterpieces,” he wrote in a 1969 document included in the exhibition catalog.

On the cover of the catalog are images of the punch cards VanDerBeek used to program his films, all numbers and raw data. They resemble the punch cards in Errol Morris’ film The Fog of War, cards that Robert McNamara employs in his coolly efficient planning of the Vietnam War. Technology is not inherently good or bad, but it has the potential to be used for vastly different ends. VanDerBeek realized this dichotomy, noting that his work offered “a possible way to replace ‘war’ games with ‘peace’ games.” The most lucid example of this is Poemfield No. 7 (1967-8), which reproduces the poem “There is no way to Peace – Peace is the way” by anti-war activist A.J. Muste. The most serene film in the show, the poem’s words unfold across a cruciform mandala that recalls multiple spiritual sources.

Stan VanDerBeek: Poemfield at the Box, Los Angeles; installation view. Courtesy of the Estate of Stan VanDerBeek and the Box, L.A. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

The one drawback of the show is the works’ sonic environment. VanDerBeek used notable musicians like John Cage and Paul Motian to create soundtracks for each film, but the sounds are not isolated, and in the Box’s cavernous main space they play over each other in a sea of aural cacophony. In adjoining galleries, other films are played on monitors that have headphones, making it all the more apparent how important the unique soundtrack is to each work.

Despite this limitation, the exhibition is a welcome restoration of a digital pioneer whose work bridged high art, progressive ideals, and technology. Instead of encouraging isolation, VanDerBeek saw the computer and the cinema as tools to connect people and enable communication. As he writes in an article on “Disposable Art” (also included in the catalogue), “I believe that motion pictures and related image-thinking holds out a hope for ‘seeing’ ourselves and thus to evolve the ecology most suitable for life, for living…can you see me! can you hear me!”

Stan VanDerBeek: Poemfield is on view at the Box in Los Angeles through November 1, 2014.