Cleveland

In ___ We Trust: Art and Money at the Columbus Museum of Art

Curator Tyler Cann’s In ___We Trust: Art and Money is a fresh and imaginative approach to exhibition making. The title definitively removes higher moral or spiritual motives—so often claimed in art making—from the framework of the exhibit, and it seems especially fitting that Andy Warhol, a lover of all things material and monetized, opens the show. Hanging on the first wall are three works: the print One Dollar Bills (1962), the drawing Five Dollar Bill (1962), and a project by Komar and Melamid called Souls Project: Andy Warhol (1979), in which Warhol sells his soul to the duo for zero dollars. Though these objects feel a bit thin as historical context, they operate alongside the title wall to underscore the interdependence between contemporary art and money.

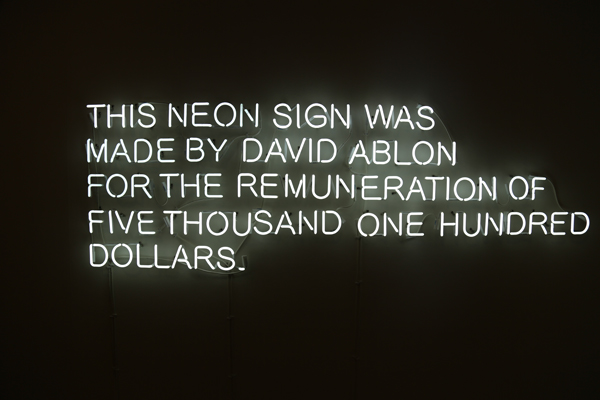

Claire Fontaine. This Neon Sign Was Made By…, 2009; back-painted neon, 6400k glass, cables, fixtures and transformers; 19 11/16 x 118 1/8 in. Courtesy of the Artist and Metro Pictures, New York. Photo: Erin Fletcher.

As a whole, the exhibition doesn’t seek to be subversive in its mode of delivery or to propose solutions to the underlying tensions that are activated. However, several of the works use activist tactics, or use their cultural position as art to create commentary on ethics. A tone of doubt and mistrust toward the international banking system is set by Superflex’s Bankrupt Banks (2008–present). Seventeen oversize panels list the names of all the banks, as on a mass grave, that collapsed due to the financial crisis. Between each panel is a banner (thirteen in total) of an iconic image that was part of a bank’s branding, meant to build trust but now stripped of a name and institutional affiliation to back up the promise. These line the halls outside of the galleries like tapestries, and visitors pass them as they enter and exit. In Insertions Into Ideological Circuits 2: Banknote Project (1970/2014), Cildo Miereles uses currency for its ability to circulate stamped messages and questions that would be censored in everyday speech by a dictatorship.

Superflex. Bankrupt Banks, 2008 – present; banners: paint on fabric, 79 x 79 in; panels: vinyl on painted MDF, 79 x 39.5 in. Coppel Collection. Courtesy of Nils Staerk and Fundación Jumex Arte Contemporáneo.

Another group of objects use valuable materials as a medium to call attention to notions of value. An installation by Susan Collis called Lavartus Prodeo (2014) appears to be a series of holes and screws in the wall, but on closer inspection these are made from gemstones and other precious materials, calling attention to some notions of value surrounding framed and hung art. Mark Wagner’s collage Liberty Installation (2011) creates a whimsical narrative with the Statue of Liberty as the backdrop, which is composed from 1,121 one-dollar bills. Ester Partegàs’s oversized hand-drawn receipts call out the familiar connection between consumerism and psychology with phrases like “JUST FOR FUN” where each word stands in for a purchased item. Gabriel Kuri’s Untitled (2012) uses skilled labor to turn his restaurant and market receipts from three countries into large, woven hangings, calling attention to wealth’s command of labor. Finally, Claire Fontaine’s This Neon Sign Was Made By… (2009) makes the purchase and cost of the work its subject. All of these works are compelling and thoughtful in approach, though none of them seem to turn the corner from awareness to a deeper reckoning with privilege.

Left to Right: Mark Wagner. Liberty Installation, 2011; currency collage on 13 panels. Ester Partegàs. Detours (Series), 2014; pencil, watercolor, marker, acrylic, paper. Courtesy of Christopher Grimes Gallery and Foxy Production. Gabriel Kuri. Untitled, 2013; hand-woven wool gobelin. Courtesy of the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Center: J.S.G. Boggs. Boggs Bank of Bohemia, 2014; children’s drawings of $1 bills. Photo: Erin Fletcher.

Cann also incorporates a number of participatory works in Art and Money. In addition to creating deeper engagement in the galleries, these moments force viewers to decide whether they wish to support each work’s statement with their participation. We Make Change (2008) by Paul Ramírez Jonas offers a penny-press machine in which to flatten pennies so that they bear the words “TRUST” on one side and “WE” on the other (which can also read as “ME”). Other works like Roger Hiorns’ untitled installation(2012) feel more aggressive, as it spits pennies with the word “GOD” crossed out into the gallery. Gallery-goers can create this same effect with a penny of their own by placing it in a nearby stamping press and hitting the stamp with a hammer. Caleb Larson’s $10,000 Sculpture in Process (2009) accepts bills from viewers for the support of his artistic practice. Of all of these, the most playful is also a work that encourages participants to continue it beyond the parameters of the exhibition. In Boggs Bank of Bohemia (2014), J.S.G. Boggs invites children to draw one-dollar bills and try to spend them.

e-flux. Time/Bank, 2010-present; mixed media; dimensions variable. Courtesy of Julieta Aranda and Anton Vidokle. Photo: Erin Fletcher.

Overall, Cann’s approach is to survey so many different attitudes and relationships between art and money that it leaves the viewer with the sense that the relationship to the topic is one of acceptance and ambivalence. The directness of the address is welcome, but the equivocation as a whole left this viewer with two questions beyond the scope of the exhibition: “What do we trust?” and “What are our alternatives?” Two works speak to these questions. Ori Gersht’s looping video installation Liquid Assets-A Portrait of Euthydemas II, King of Bactrica 180 BCE (2012) presents a shifting puddle of liquid metal that slowly settles into the form of a coin from a lost empire located near modern-day Afghanistan. Like the dynamic and unstable region it represents, this video suggests we can trust that change will happen regardless of money or ruling system. The final installation in the exhibit, by e-flux, Time/Bank (2010–present), builds on the idea of the time bank.[1] Beginning with the Cincinnati-based anarchist Josiah Warren, who operated a time-bank store for three years in 1827, this installation presents an ongoing work with video components, an archive for research, a table for discussion, and a wall filled with ways that people have exchanged their time for services. These two works left me with a lingering curiosity to see where this exhibit could have ended up if it had stretched beyond exposé and oriented toward a deeper social, psychological, historical, and political analysis of the relationship between wealth and culture.

In ___ We Trust: Art and Money is on view at the Columbus Museum of Art through March 1, 2015.

Erin Fletcher graduated with an MA from John F. Kennedy University in Museum Education and Interpretation in 2010 and an MA in Curatorial Practice from the California College of the Arts in 2011. Her research interests are in gender and performance, art in public space, and the relationship between art and activism.

[1] E-flux describes a time bank as “a tool by which a group of people can create an alternative economic model where they exchange their time and skills, rather than acquire goods and services through the use of money or any other state-backed value.” http://e-flux.com/timebank/