Help Desk

Help Desk: The Ethics of Application Fees, part 2

Help Desk is an arts-advice column that demystifies practices for artists, writers, curators, collectors, patrons, and the general public. Submit your questions anonymously here. All submissions become the property of Daily Serving.

What are your thoughts on application fees for residencies, fellowships, and exhibitions? Typically the odds of being selected are very long, and the vast majority of artists who apply for opportunities aren’t swimming in cash they earn (for making and selling work). I understand that institutions, organizations, and other entities offering opportunities are on tight budgets, and the massive inflows of applications are insane to deal with, but shouldn’t they have to incorporate the expense into their costs of doing business? I know using services like Slide Room costs money, but sticking a fee on an artist with a less than 10 percent chance doesn’t seem quite right.

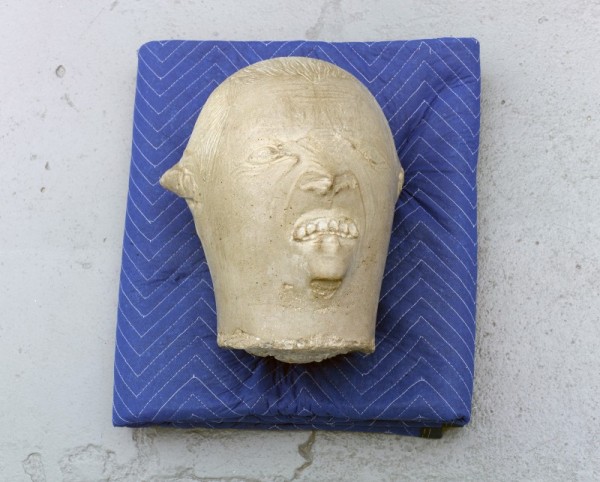

Jean-Luc Moulene. Tronche/Avatar (Paris, April 2014), 2014; polished concrete, blue blanket;

15 x 10 5/8 x 11 in.

Like many artists, my thoughts on application fees are mixed. I’ll happily pay about $25—my personal threshold—for what is essentially an art lottery ticket, but much more than that and I get queasy. Like you, I’m aware that no matter how good my targeting skills are, it’s still a crapshoot. As artist Christine Wong Yap’s blog shows us, the odds are often quite low: a 10 percent chance of securing a 2015 residency at Djerassi; a 3.7 percent acceptance rate for a visual-arts residency at the Headlands Center for the Arts; and a one-in-fifty-six probability—that’s 0.3 percent, so maybe better to call it an improbability—of becoming one of three Emerging Artist Fellows at the Queens Museum in New York City. But the odds are long on almost everything in life, and as a pal of mine used to remind me, “You can’t win the lottery if you don’t buy a ticket.”

I’m familiar with artists’ gripes about entry fees, but I wanted to hear the institutional side of the story. Jason Franz, executive director of the ten-year-old Manifest Gallery in Cincinnati, was eager to engage in a lively email conversation on the subject. He started off by putting the idea of financial risk into context: “The odds of making a masterful work of art that will sell for thousands of dollars with the materials purchased to do so are probably even slimmer than success in submitting to competitive juried exhibitions. Does this mean the art-supply store should give away the materials or in some other way negotiate your risk? For one to say, ‘Shouldn’t [institutions] have to incorporate the expense into their costs of doing business’ shows a severe naiveté. Shouldn’t artists have to incorporate the expense into their costs of doing business? I know I do as a working artist.”

“If ‘sticking a fee on an artist’ with less than a 10 percent chance doesn’t seem quite right, then selling the artist art supplies doesn’t seem quite right, nor does charging tuition for a BFA or MFA. But this assumes that the fee-charging institution, art-supply store, and university are forcing the purchase. But the artist has a choice.”

Franz also provided clarity on exactly why some institutions charge fees: “Our organization is nonprofit, state-recognized, and state-funded. We obtain the limited grant funding we do because we have such a strong record of earned revenue (i.e., entry fees). Grant agencies want to see sustainability and a ‘public vote’ if you will, and artists paying entry fees hits the nail on the head. It means they trust and value what we’re doing. They vouch for us. To remove the entry fee removes the public statement from key constituents (the artists), thereby weakening, if not completely degrading, our grant-writing platform. It also removes one of the most compelling facts about the existence of our organization. As a public charitable entity, we derive a meaningful proportion of our operating expenses from those who stand to gain the most—namely the artists themselves—in small but incremental amounts.”

Franz went on to play devil’s advocate: “Just for argument’s sake, let’s remove the fees. What then? We could sell each exhibit to the highest bidder, but this would mean that instead of paying a small share to actively compete in a rigorous jury process, artists would have to fork over thousands of dollars for an exhibition. This would eliminate all those artists who aren’t swimming in cash and make our principle-driven organization into a vanity gallery. Or we could get lucky and find a wealthy patron to underwrite all our costs, but this patron would likely put qualifications on what we do and how we do it. Suddenly, because a patron is footing the bill, the identity of the organization becomes compromised and tied down by a personal agenda. Who loses in this scenario? The artists, because the venue is no longer about them. Or we could change our goals with the intention of replacing funds from entry fees with sales. As our budget stands this year, this would mean selling about $350,000 worth of art. But we are not salespeople; we’re artists and professors, and this is an incredibly high number for a midsized nonprofit to be reaching for in art sales (I would say it is probably very high for 90 percent of the art galleries in the U.S.). This would inevitably mean two things: First, we would need to fire existing staff, eliminate programs, and hire people expert in selling art. Second, it would mean our selection would be done by a process that considers only salability.”

But really, what are the alternatives for artists? To quote Franz again, “We all have to make informed choices, and there is rarely an absolute rule one can apply to all of them.” Rather than deciding to either heartily endorse or vehemently oppose fees, try applying a rigorous strategy to your process. Start by researching the jurors: Based on their own work or the work they generally curate, are they likely to appreciate yours? How about the venue—what do they usually show? If you can find the past participants for a fellowship or residency, check out their websites and see if your work and CV are on a similar level. You can also find out the likely odds by contacting the organization and asking for previous years’ statistics and the number of people who will be accepted in the current round—though you can’t know how many artists will apply this time, you’ll be able to guesstimate whether you’ll be part of an applicant pool of tens or thousands. Set a yearly budget for application fees and stick to it; it will keep you focused on your best chances.

My personal methodology also involves an genuinely cheerful presumption that I won’t get into anything that I apply for. This may sound defeatist to some, but for me it serves two purposes: First, I’m way less disappointed when I get a rejection letter, which is advantageous for my long-term mental health. Second, it compels me to think of my application fee as a donation; when reclassified as a form of support, I consider it more carefully. Do I want my money to go to a well-regarded institution that provides a lot of free public programming and/or high-quality support for artists, or do I want to PayPal a privately funded space that probably doesn’t need my help?

Of course, there are juried exhibitions and other opportunities that don’t involve fees. For example, here in San Francisco, Southern Exposure hosts an annual show that is fee-free and juried by a reputable curator; there are probably similar exhibitions in every major city. There are also countless ways to make opportunities for yourself, from studio visits to pop-up shows to self-funded residencies. Good luck!

* * *

Update, November 17, 2014: After the deadline had passed, I received a response from the director of an arts organization in New York. For various reasons, she asked to remain anonymous; her comments are below:

“For a small nonprofit whose programs are still in its early stages of development (with limited funding resources), it comes down to a choice of either not offering the services/opportunities at all or asking the artists to chip in until more resources can be secured for the program. Securing funding is a sticky situation, as no one will fund a program that does not exist yet, and hence the program has to be successfully running before funders will decide to support it. We are still at that stage where we are trying to court more funders and donors to support us so that these much-needed resources and services for artists can eventually be offered for free.

“As an artist, one should always be wary of opportunities that ask for an application fee. However, there are good opportunities out there that may still be asking for a fee due to financial restraints, and the artists need to research the organization/hosting entity carefully before deciding if the opportunity is appropriate and worth it for them. Understanding the mission of the organization would be a good start, and researching what kind of artists they work with is essential. For example, there is a very fine line between opportunities involving juried exhibitions that seem to be focused on getting a lot of applicants for financial gain, and ones that are truly trying to benefit the artist by providing greater exposure.

“One example that I can give is from a few years ago: I was organizing an open call involving a museum curator as a juror. Although there was only one winner for the open call, the museum curator asked to take the top 10 artist CVs with him when he left. That itself was a very rewarding moment, to know that a museum curator was introduced to the work of the top nine runners-up and liked them enough to want to remember and continue to follow their work.

“I have also been on a review panel where the jurors discussed the progress that a particular artist was making. One of the jurors had reviewed the artist’s work a couple of times before, saw a huge improvement in the work, and made a point of commenting about it during the judging. Basically, endorsing an artist who may not be the best but had great potential. So not all paid application opportunities are a lost cause for artists who don’t get ‘selected’ for a show, fellowship, or residency.

“As a professional artist, your first instinct would be to avoid any opportunities that require payment. However, if there seems to be a good program or opportunity that fits your need, it might be worth chipping in toward a small processing fee since online application-form hosting, administrative labor for downloading, organizing, reviewing applications, following up, and logistical and marketing support, etc., all does add up, even if the cost of the program itself is covered through other funding sources. If the opportunity seems like something the organizers are having the artists foot the bill for the entire exhibition or cost of the opportunity itself, then I would advise against applying to such opportunities (for example, they ask the artists to pay a fee to be included in the exhibition).”