London

Louise Bourgeois: A Dangerous Obsession

Louise Bourgeois’ life is not just any open book – it more resembles a multi-volume anthology with pages torn out, chapters re-written, and notes cryptically hidden in the margins. While Bourgeois spoke openly about many of the subjects which infiltrate in her work, including the difficult relationship she had with her adulterous father and her traumatising childhood, she did not share unconditionally, and as we have discovered, held to a few of secrets for herself.

Louise Bourgeois working on Sleep II in Italy, 1967. Photo: Studio Fotografico, Carrara. © The Easton Foundation.

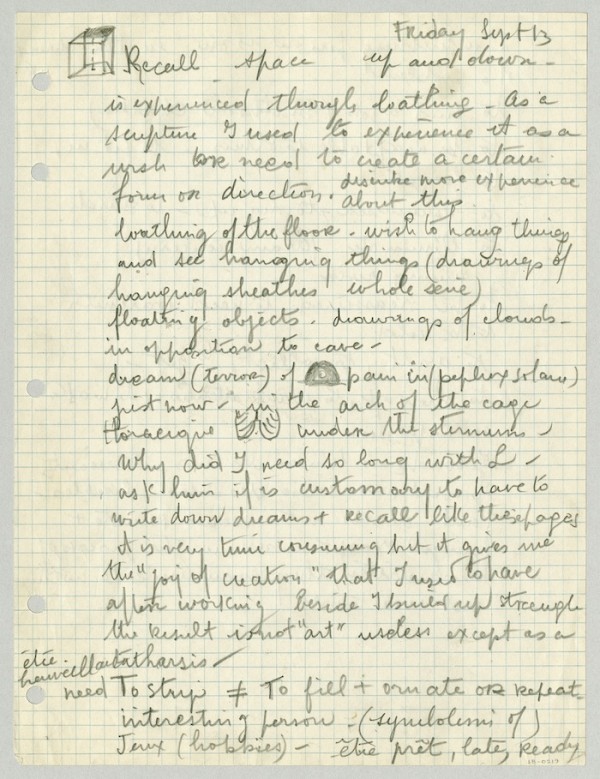

In 2004, two boxes of what have been labelled Bourgeois’ ‘psychoanalytical writings’ were discovered by her assistant in her Chelsea home, and a further two in 2010. These thousands of loose-leaf sheets of paper recorded Bourgeois’ inner conflicts, dream recordings and self-probing analysis, commencing during the period when the artist began undergoing intense psychoanalysis at the hands of Dr. Henry Lowenfeld, a follower of Sigmund Freud.

Louise Bourgeois, loose sheet, 13 September 1957, 26.7 x 20.3 cm. LB-0219, Louise Bourgeois Archive, New York. © The Easton Foundation.

With these in hand, curator Phillip Laratt-Smith published a volume of Bourgeois’ writings, and conceived the exhibition, Louise Bourgeois: The Return of the Repressed. Currently tucked away in residential North London, the works could not have found a more suitable site than The Freud Museum – a home firmly entrenched in psychoanalytic history, where both its patriarchal namesake, and his daughter Anna, remained until their deaths.

With Bourgeois’ writings, drawings and sculptures housed throughout Freud’s former possessions and collections, a challenging and quite perilous dialogue is created, laying the groundwork for a very dangerous obsession that may inextricably fuse Bourgeois to Freud.

Louise Bourgeois's bronze Janus Fleuri, 1968, suspended over Freud's couch at The Freud Museum, London. Courtesy The Easton Foundation. Photo: Ollie Harrop. © Louise Bourgeois Trust.

Hanging above Freud’s psychoanalytic couch, the original brought with him from Vienna, is a work by Bourgeois often referred to as a self portrait of the artist. The bronze sculpture Janus Fleuri is a ambiguous form with connotations of sexuality, metamorphosis, and struggle. Swaying above the place where free association was born, Janus Fleuri looks both to the past and to the future, and as Laratt-Smith has argued, embodies the artist’s Oedipal deadlock – an unresolvable struggle between Bourgeois, her father and her mother, stalemated by her mother’s death.

Louise Bourgeois, Cell XXIV (Portrait), 2001, steel, stainless steel, glass, wood and fabric, 177.8 x 106.7 x 106.7 cm. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth and Cheim & Read. Photo: Christopher Burke. © Louise Bourgeois Trust.

Bourgeois’ work functions as an expression of her psychic unconscious – a way of giving form to anxieties she could not articulate, which she then subsequently analysed in her writings. While Freud focused on ‘the word’ – translating thoughts and dreams into articulations – Bourgeois moved freely between the two. Her writings reveal struggles, at times debilitating, to define herself within the roles of mother, daughter, wife and artist. And works like Cell XXIV (Portrait), embody this struggle. With three heads and three mirrors, Cell XXIV presents a multiplious identity further broken down by its external reflections – the kind of fragmented view of the self that Bourgeois struggled with throughout her life.

But it is this struggle, and her torment, that fueled her work. This Bourgeois understood well. Speaking specifically about Freud, Bourgeois wrote:

‘The truth is that Freud did nothing for artists, or for the artist’s problem, the artist’s torment - to be an artist involves some suffering. That’s why artists repeat themselves – because they have no access to a cure … the need of artists remains unsatisfied, as does their torment.’

While Bourgeois embraced Freudian psychoanalysis, she was aware of its limitations for herself as an artist. Her writings were not an attempt to cure herself or ease her suffering, but were rather used as fuel for the fire. And it is here, with Freud and Bourgeois under the same roof, that we find ourselves immersed in the realm of a very dangerous obsession.